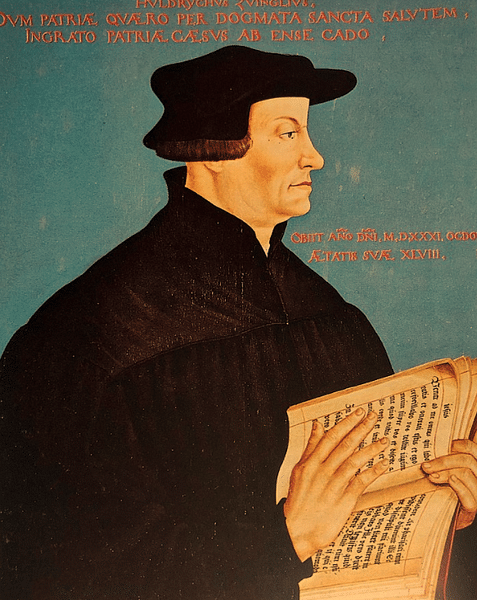

George Blaurock (l. c. 1491-1529) was one of the three founders of the Swiss Brethren (known by their opponents as Anabaptists) along with Conrad Grebel (l. c. 1498-1526) and Felix Manz (l. c. 1498-1527). His Origin of the Anabaptists is an account of how the sect began as well as its persecution by the Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli (l. 1484-1531).

Blaurock, Grebel, and Manz were initially drawn to Zwingli's teachings but broke with him after the Second Disputation of 1523 when they felt Zwingli had compromised himself on a number of important theological points, including infant baptism, in order to win favor with the city council. Blaurock and the others rejected the Catholic sacrament of infant baptism claiming it had no basis in scripture, but Protestant leaders like Zwingli and Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) continued to insist on its legitimacy.

The Swiss Brethren came to be known as Anabaptists (rebaptizers) by their enemies as they performed adult baptism in keeping with what they saw as ample evidence from the Bible to support the practice. In 1525, the canton of Zürich outlawed adult baptism and, in 1526, made it a capital offense, both ordinances supported by Zwingli. Manz was arrested and executed after he refused to stop, Blaurock was beaten and exiled, and Grebel, who had left the city to rally support elsewhere, died on his travels, most likely of plague.

Blaurock made his way to Tyrol in 1527 and is thought to have dictated his Origin of the Anabaptists to a scribe or written it down himself before he was arrested and burned at the stake for heresy in 1529. The work is included in the Hutterite Chronicle, the history of the Hutterites (also known as Tyrolean Anabaptists) founded by Jakob Hutter (d. 1536), another Anabaptist leader, and the extant text dated to 1542. The work is one of many examples of the correlation between the printing press and the Protestant Reformation as Blaurock's account, thought to have been published prior to 1542, presents a very different view of Zwingli's ministry than his own works c. 1524, though both, thanks to the power of print, would have left it up to an individual reader to decide which was telling the truth.

Background to the Anabaptists

Zwingli arrived in Zürich in 1519 as a Catholic priest appointed to the Gross Münster (Great Church) and almost instantly began his reformation efforts by discarding the Latin liturgy and reading to his congregation directly from the Gospel of Matthew in the vernacular. His sermons and commentary on the Bible quickly became popular, drawing large crowds, including Grebel and Manz. In 1522, Zwingli openly broke with the Church after the event known as the Affair of the Sausage when he was present at a dinner where sausage was served to guests during Lent, breaking the Lenten prohibition on eating meat.

Zwingli defended those at the dinner by noting that the Lenten fast – and Lent itself – was not supported by scripture. He then went further in two sermons denouncing the practice, claimed many of the Church's traditions were artificial obligations unsupported by the Bible, and he articulated his new vision of Reformed Christianity through his 67 Articles. Zwingli's 67 Articles of faith then informed the First Disputation with Catholic delegates in January 1523 which he won, establishing his vision as the dominant understanding of Christianity in Zürich.

Grebel and Manz were among many who had followed Zwingli's admonition to study the scripture for themselves and held regular Bible study meetings. Zwingli's insistence on biblical supremacy in all things encouraged Grebel and Manz to question aspects of his vision that were no more in line with the Bible than what he was criticizing in Catholicism, notably infant baptism. Zwingli had rejected all the Catholic sacraments except infant baptism and the Eucharist, but Grebel and Manz now claimed he had retained the same 'artificial obligations' he had preached against by insisting on the legitimacy of infant baptism, tithes, and a Christian's duty to serve in the military.

Break with Zwingli

After the Second Disputation in 1523, Zwingli condemned Grebel and Manz as rebels, denouncing them in his sermon Whoever Causes Unrest in 1524. The city council tried to reconcile the two sides in 1525, but neither would listen to the other or compromise on any of the issues, especially infant baptism. The Anabaptists claimed that the Bible clearly showed how John the Baptist had performed adult baptisms as had the disciples of Jesus Christ, but Zwingli countered that John's ministry had taken place before the trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth – which had washed away all sin – while the later acts of the apostles were simply a means of confirming one's commitment to Christ and separation from one's old beliefs.

To Zwingli, infant baptism was a valid sacrament because it was an adult's profession of faith for the child, which confirmed the parents' recommitment to the Church and observed a tradition that the child would one day continue. Adult baptism, when one had already been baptized as an infant, he claimed, was a rejection of Christ's sacrifice and an act of pride in that one was claiming one had the authority to baptize another into the remission of sin. Zwingli later wrote (in 1527) how the Anabaptists were only interested in fighting for the sake of argument, as they had no biblical support for any of their claims, and started all the trouble to advance a hidden agenda:

They denounced infant baptism tremendously as the chief abomination, proceeding from an evil demon and the Roman pontiff. We met this attack at once, promised an amicable conference. It was appointed for Tuesday of each week. At the first meeting the battle was sharp but without abuse, as we especially took in good part their insults…The second was sharper. Within three, or at most four, days it was announced that the leaders of the sect had baptized fifteen brethren. Then we began to perceive why they had determined to collect a new church and had opposed infant baptism so seriously: they had attempted a division and partition of the church, and this was just as hypocritical as the superstition of monks. (Lindberg, Source 7.1, p. 121)

To Zwingli, Grebel, Manz, and later Blaurock were just seeking power at Zwingli's expense. They wanted, he claimed, to make the rules of the church at Zürich as they saw fit rather than submit to authority. The Anabaptists claimed Zwingli was a hypocrite and a people-pleaser rather than a man of God who had forsaken his earlier convictions once he had attained a respectable position in the city. Zwingli dismissed their claims and supported the city council in the 1525 mandate outlawing adult baptism in the city as well as the second 1526 mandate making it a capital offense.

The Text

The following account describes the early meeting in January 1525 of Blaurock, Grebel, and Manz at which they baptized each other and committed themselves to preaching their vision of Christianity, which they held to be the only true one. This was precisely the same claim Zwingli had made when he established his Reformed vision in Zürich and denounced the Catholic Church. The account is purposefully modeled on biblical narratives in tone and style and presents the central figures as devout Christians willing to die for their faith; an image Zwingli also had cultivated for himself earlier.

The text is taken from A Reformation Reader: Primary Texts with Introductions, edited by Denis R. Janz, pp. 200-201, cross-referenced with the longer account given in Spiritual and Anabaptist Writers edited by George Williams, pp. 41-46. The original text reprinted in both works comes from The Hutterite Chronicles (1542), a collection of works giving the history of the Anabaptists and Hutterites, and is only one part of The Reminiscences of George Blaurock:

It came to pass that Ulrich Zwingli and Conrad Grebel, one of the aristocracy, and Felix Manz – all three much experienced and men learned in the German, Latin, Greek, and also the Hebrew, languages – came together and began to talk through matters of belief among themselves and recognized that infant baptism is unnecessary and recognized further that it is in fact no baptism. Two, however, Conrad and Felix, recognized in the Lord and believed further that one must and should be correctly baptized according to the Christian ordinance and instruction of the Lord, since Christ himself says that whoever believes and is baptized will be saved. Ulrich Zwingli, who shuddered before Christ's cross, shame, and persecution, did not wish this and asserted that an uprising would break out. The other two, however, Conrad and Felix, declared that God's clear commandment and institution could not for that reason be allowed to lapse.

At this point it came to pass that a person from Chur came to them, namely, a cleric named George of the House of Jacob, commonly called "Bluecoat" (Blaurock) because one time when they were having a discussion of matters of belief in a meeting, this George of Jacob presented his view also. Then someone asked who it was who had just spoken. Thereupon someone answered: The person in the blue coat spoke. Thus, thereafter he got the name Blaurock…This George came, moreover, with the unusual zeal which he had, a straightforward, simple parson. As such he was held by everyone. But in matters of faith and in divine zeal, which had been given him out of God's grace, he acted wonderfully and valiantly in the cause of truth.

He first came to Zwingli and discussed matters of belief with him at length but accomplished nothing. Then he was told that there were other men more zealous than Zwingli. These men he inquired for diligently and found them, namely, Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz. With them he spoke and talked through these matters of faith. They came to one mind in these things, and in the pure fear of God they recognized that a person must learn from the divine Word and preaching a true faith which manifests itself in love, and receive the true Christian baptism on the basis of the recognized and confessed faith, in the union with God of a good conscience prepared henceforth to serve God in a holy Christian life with all godliness, also to be steadfast to the end in tribulation.

And it came to pass that they were together until fear began to come over them, yea, they were pressed in their hearts. Thereupon, they began to bow their knees to the most high God in heaven and called upon him as the knower of hearts, implored him to enable them to do his divine will and to manifest his mercy toward them. For flesh and blood and human forwardness did not drive them, since they well knew what they would have to bear and suffer on account of it.

After the prayer, George of Jacob arose and asked Conrad to baptize him, for the sake of God with the true Christian baptism upon his faith and knowledge. And when he knelt down with that request and desire, Conrad baptized him, since at that time there was no ordained deacon to perform such work. After that was done, the others similarly desired George to baptize them, which he also did upon their request. Thus, they together gave themselves to the name of the Lord in the high fear of God. Each confirmed the other in the service of the gospel and they began to teach and keep the faith. Therewith began the separation from the world and its evil works.

Soon thereafter, several others made their way to them, for example Balthasar Hubmaier of Friedberg, Louis Haetzer, and still others, men well instructed in the German, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew languages, very well versed in Scripture, some preachers and other persons, who were soon to have testified with their blood.

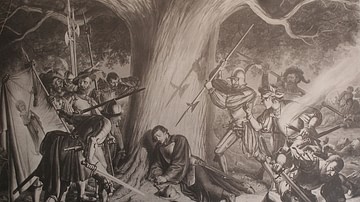

The aforementioned Felix Manz they drowned at Zurich because of this true belief and true baptism, who thus witnessed steadfastly with his body and life to this truth.

Afterward, Wolfgang Ullmann, whom they burned with fire and put to death in Waltzra, also in Switzerland, himself the eleventh, his brethren and associates witnessing in a valorous and knightly manner with their bodies and their lives unto death that their faith and baptism were grounded in the divine truth…

Thus did the movement spread through persecution and much tribulation. The church increased daily, and the Lord's people grew in numbers. This the enemy of the divine truth could not endure. He used Zwingli as an instrument, who thereupon began to write diligently and to preach from the pulpit that the baptism of believers and adults was not right and should not be tolerated – contrary to his own confession which he had previously written and taught, namely, that infant baptism cannot be demonstrated or proved with a single clear word from God. But now, since he wished rather to please men than God, he contended against the true Christian baptism. He also stirred up the magistracy to act on imperial authorization and behead as Anabaptists those who had properly given themselves to God, and with a good understanding had made covenant of a good conscience with God.

Finally, it reached the point that over twenty men, widows, pregnant wives, and maidens were cast miserably into dark towers, sentenced never again to see either sun or moon as long as they lived, to end their days on bread and water, and thus in the dark towers to remain together, the living and the dead, until none remained alive – there to die, to stink, and to rot. Some among them did not eat a mouthful of bread in three days, just so that others might have to eat.

Soon also there was issued a stern mandate at the instigation of Zwingli that if any more people in the canton of Zurich should be rebaptized, they should immediately, without further trial, hearing, or sentence, be cast into the water and drowned. Herein one sees which spirit’s child Zwingli was, and those of his party still are.

However, since the work fostered by God cannot be changed and God's counsel lies in the power of no man, the aforementioned men went forth, through divine prompting, to proclaim and preach the evangelical word and the ground of truth. George Blaurock went into the county of Tyrol. In the meantime, Balthasar Hubmaier came to Nicolsburg in Moravia, began to teach and preach. The people, however, accepted the teaching and many people were baptized in a short time.

Conclusion

Shortly after their meeting, Grebel left Zürich to preach the Anabaptist vision elsewhere and rally support while Manz and Blaurock remained in the city. Throughout 1526, Manz continued the practice of adult baptism until he was arrested and executed in January 1527, and that same day, Blaurock was severely beaten and exiled. The passage above in which Blaurock speaks of the "over twenty men, widows, pregnant wives, and maidens" imprisoned and deprived of anything but bread and water is a scenario repeated across Europe as Anabaptists were persecuted by both Catholics and Protestant sects.

Blaurock is accurate in his assertion that the movement "spread through persecution and much tribulation" as many of the European court records of the latter part of the 16th and the early 17th century detail the execution of Anabaptists, often in large numbers. Zwingli oversaw the drowning of three more in Zürich before the others left. The Anabaptists made use of the printing press just as other Protestant sects and the Catholic Church did to win people to their cause and denounce the practices and beliefs of their opponents, but their willingness to die for their faith seems to have attracted more converts than any pamphlet or tract.

It is unclear how wide a circulation Blaurock's account had in the years after his death, but considering how popular Protestant works were in the 16th century, it was probably significant. Blaurock did not have the name recognition of Zwingli, however, especially after the latter's death in the Kappel Wars in 1531 when he was hailed as a martyr. His reputation as a defender of the true faith was furthered by his successor, Heinrich Bullinger (l. 1504-1575), who, though much more moderate, also rejected the claims of the Anabaptists.

Zwingli had driven them out of Zürich by late 1527 when he wrote his Refutation of the Tricks of the Baptists, and thanks to the printing press, his interpretation of the Anabaptist movement became more widespread than Blaurock's account of his betrayal of those who had initially admired him. Blaurock's account remained an important text among Anabaptist congregations, however, and is said to have inspired more conversions. The Anabaptists persevered through the trials informed by Zwingli's account, and those of others also circulated in print, to influence the development of the Hutterites, Amish, Mennonites, Bruderhof, and other similar Christian sects still active in the present day.