The staggering quantity of gold the conquistadors extracted from the Americas allowed Spain to become the richest country in the world. The thirst for gold to pay for armies and gain personal enrichment resulted in waves of expeditions of discovery and conquest from 1492 onwards. In only the first half-century or so of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, over 100 tons of gold were extracted from the continent.

In melting down this glittering metal, the conquistadors left behind a trail of death, torture, and destruction. The conquistadors massively reduced the number of artefacts which may have otherwise survived to this day, artefacts which could have spoken of the religious, cultural, and artistic significance their creators had once given them. It had been their hope that their choice of incorruptible gold would make these objects endure for generations, instead, it sealed their fate to be lost forever.

The Thirst for Gold

When Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) arrived in the Americas in 1492, the one commodity that all European monarchs craved was gold. With this precious yellow metal, armies, mercenaries, and gunpowder weapons could be paid for, and their kingdoms could be defended and expanded. Gold has always been rare, but at the end of the 15th century, it was exceptionally so in Europe. Perhaps surprisingly, if all the gold in Europe at that time had been collected together in one place, it would have taken up the volume of a mere 2 m (6 ft) sided cube. That would still have weighed 88 tons, but the gold the conquistadors were about to stumble upon in the New World would dwarf this paltry sum and enrich the Spanish Crown beyond its wildest dreams.

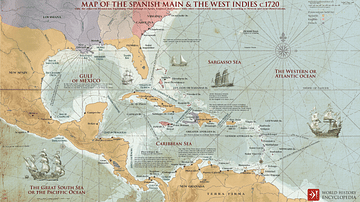

The conquistadors first found gold on the island of Hispaniola (modern Dominican Republic/Haiti) in 1494. The tentacles of the empire then spread to Puerto Rico in 1508, Jamaica in 1509, and Cuba in 1511, so far the best source of gold. In the spring of 1513, Juan Ponce de León (1474-1521) was the first European to make a documented landing in Florida. Also in 1513, Vasco Núñez de Balboa (1475-1519) crossed the Isthmus of Panama and so became the first European to sight the Pacific Ocean. In the 1520s, the Spanish colonialization process went up another gear. Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465-1524), the Governor of Cuba, sent Hernán Cortés (1485-1547) to explore Mexico, where he encountered and then conquered the Aztecs from 1521. Then Pedro de Alvarado (c. 1485-1541) led the brutal conquest of the Maya in Guatemala in 1524. Next came Francisco Pizarro (c. 1478-1541), who plundered Inca Peru from 1532, and then Hernando de Soto (c. 1500-1542), who began exploring North America as far as the Mississippi River in 1539-42. All of these men were after wealth of any kind, from emeralds to exotic hides, but the most coveted material of all was gold.

The Americas did indeed turn out to be an excellent place to find gold. Although the metal was not valued for its rarity or as a means of payment by the indigenous peoples of the Americas, it was esteemed because of its lustre, incorruptibility, spiritual associations (especially concerning the sun), and workability in the hands of craftsmen. For these reasons, it was mined, traded, and given as tribute across the continent. When the visitors from the Old World arrived and saw such treasures hanging from the bodies of the people they encountered and saw the glittering artefacts on the walls of their temples, they were overjoyed. This exultation puzzled the Americans since they typically valued other materials more highly, such as jade, turquoise, exotic feathers, and well-woven fabrics.

Aztec Gold

When Cortés began the conquest of Mexico in 1519, the search for gold was foremost in his mind and the primary motivation of his fellow conquistadors. The superior weapons of the conquistadors, their aggressive and total war tactics, and the brilliant use of local allies all conspired to bring the Spanish victory after victory and ultimate control of the last great empire in Mesoamerica's long history.

When Cortés had met the Aztec ruler Motecuhzoma (aka Montezuma, r. 1502-1520) in November 1519, things had started well in the search for gold when the conquistador was presented with a magnificent necklace of golden crabs. With the fall of the Aztec capital Tenochtitlan in August 1521, temples, palaces, storehouses, and private homes were looted for their valuables. Indigenous peoples were frequently captured and tortured to reveal the whereabouts of their valuables and particularly anything at all made of gold. The conquistadors were insatiable in their greed for everything from gold nose plugs to secret idols. As one contemporary native source quotes: "The Spaniards took things from people by force. They were looking for gold; they cared nothing for greenstone, precious feathers, or turquoise" (quoted in Carballo, 226).

For a more regular flow of gold, subjugated tribes were soon obliged to give the Spanish yearly tribute, often in the form of small gold discs. Naturally, the Spaniards also wanted to know where the gold had originally come from, and so the Aztec mines at Taxco and Pachuca were taken over. New gold and silver mines were created at Taxco (1536), Zacatecas (1546), Guanajuato (1550), Pachuca (1552), and San Luis Potosí (1592), and so the steady stream of precious metals kept on flowing back to Spain.

Inca Gold

In Peru, the conquistador Francisco Pizarro attacked the Inca Empire in 1532 and captured its ruler, Atahualpa. The Inca civilization considered gold the sweat of their sun god Inti, and so it was used to manufacture all manner of objects of religious significance, especially masks and sun disks. The Coricancha Temple of the Sun in Cusco was covered with over 700 half-metre square sheets of beaten gold, each weighing 2 kg (4,4 lbs). There was even a garden dedicated to Inti. Everything in it was made of gold and silver. There was a large field of corn and life-size models of shepherds, llamas, jaguars, guinea pigs, monkeys, birds, and even butterflies and insects, all crafted in precious metal.

The conquistadors were not slow to observe these magnificent adornments to Inca temples. The leader was promised his freedom if a massive ransom was paid, enough to fill a room measuring around 6.2 x 4.8 m (20 x 15.5 ft). Atahualpa's ransom was duly paid and then melted down in nine large forges and distributed out amongst the 217 Spaniards. The gold part of this ransom, with a purity of 22.5 carats and weighing over 6,000 kg (13,420 lbs), was valued as equal to over 1.3 million gold pesos, well over $300 million today. An infantryman received the enormous sum of 20 kilos (44 lbs) of gold, while a cavalryman got 41 kilos (90 lbs); Pizarro gave himself seven times that of a cavalryman, and the Crown was allotted its one-fifth as promised. In addition to this sum, Pizarro was obliged under the terms of his contract of conquest and adelantado status to pay the Crown a 10% tax on all the gold he acquired in Peru, a figure which rose to 20% after the first six years.

The former Inca Empire also became a massive source of silver both from looting and mining. The Incas had long used mines as a way to extract labour and tribute from specific areas. Deposits of gold were mined using narrow shafts that followed veins of the metal. There were also open mines, and gold was recovered by panning river beds. Precious metal mines were opened and exploited by the Spanish across South America for all they were worth. Major mines included the Cauca Valley mines in Colombia (opened in 1540), Potosí (1545) and Oruro (1595) in Bolivia, and the Castrovirreyna (1555) and Cerco de Pasco (1630) mines in Peru.

Silver extraction from the Americas soon came to dominate; by 1540, it made up over 85% of precious metal shipments to Spain. Throughout the 16th century and early 17th century, gold and silver always made up at least 80% of the cargoes sent to Europe in terms of their total value. The labour that extracted the gold and silver was forced in the encomienda license system, which gave its holder the right to use local labour for free in return for offering a nominal degree of security and the opportunity to be educated in the Christian religion. As diseases and poor working conditions took a severe toll on local populations, the encomienda system was eventually replaced by one of low pay, the repartimiento system.

The Gold of El Dorado

In ancient Colombia, gold was also revered for its lustre and association with the sun. In powdered form, gold was used to cover the body of the future Muisca (Chibcha) king in a lavish coronation ceremony, which gave rise to the legend of El Dorado ('Gilded Man'). The newly dusted monarch then leapt into Lake Guatavita in a ritual act of cleansing. Meanwhile, onlookers threw precious objects into the lake as auspicious offerings to the gods. By the time the conquistadors had heard rumours of this ceremony in the 1530s, the story had been embellished, and El Dorado had become not a man but a great city paved with gold.

The golden city was never found because it did not exist, but attempts were made to find out just what lay at the bottom of Lake Guatavita. In the 1580s Antonio de Sepúlveda had perhaps the most ambitious scheme when he cut a slice out of the lake's crater edge in order to drain it and find the treasure which must surely have accumulated on the lake bed. Some gold artefacts were indeed found, but before the lake could drain completely a landslide blocked the cut, and so the water level began to rise again. A long line of sorely disappointed adventurers has since followed with their, so far, unsuccessful attempts to extract gold from Lake Guatavita.

Lost Treasures

As the conquistadors were only interested in gold and not what shape it came in, they relentlessly melted artefacts down to make coins and ingots, which were easier to transport back to Europe and easier to share out amongst themselves. Sacred statues, despite the best efforts of the locals to hide them away, were found and melted down. Gold items like bracelets, necklaces, ear plugs, nose plugs, ceremonial knives, figurines, goblets, and plates were thrown into the melting pots. Although a few select pieces were sent for the gratification of the Spanish monarch, there was next to no appreciation for the religious, cultural, and artistic significance of the countless pieces that were lost forever. All that survives of the magnificent golden garden of Inti in Cusco, for example, is a single gold wheat stalk.

By 1560, the conquistadors had shipped over 100 tons of gold back to Spain, in effect, more than doubling the quantity of the precious metal now in Europe. The quantity increased in the latter half of the 16th century thanks to mining and new sources in what became the Viceroyalty of Granada (modern Colombia, Ecuador, and Venezuela), with ships delivering around 4 tons of gold each year to Seville.

The quest for gold had its price, not only on local cultures but also on the conquistadors themselves. Many expeditions that searched for the glittering metal were deadly failures, such as the 1523-4 expedition to Honduras led by Cristóbal de Olid (b. 1492). Diego de Almagro (c. 1475-1538) led a large and expensive expedition to Chile in 1535 but found no gold. Most infamous of all was the expedition led by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado (c. 1510-1554) in 1540 to explore North America in search of Cibola, a legendary group of cities rumoured to be paved with gold. Coronado found nothing of the sort. Even those who did find gold often came a cropper from their fellow cutthroat conquistadors. Cortés himself was eternally involved in legal disputes over how he had shared out his golden loot and whether he had given the Crown its fair share.

Even the Spanish in Europe suffered from this massive influx of gold and silver since it caused hyperinflation, not then a concept understood by many economists. Prices of commodities increased by 400% over the 16th century, and Spanish exports suffered as a consequence when wages rose to match. In addition, the Crown frittered away its precious metals, usually to secure loans from bankers long before the annual Spanish treasure fleets had even arrived in Europe. Then there was the threat from pirates and privateers who were keen to intercept the Spanish galleons as they crossed the Atlantic. In 1579, for example, Francis Drake captured the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción off the coast of Peru, which was taking treasure that included 26 tons of silver bullion and 36 kg (80 lbs) of gold. Storms were an even greater threat and accounted for many wrecks like the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, which was carrying a cargo worth $400 million when it was sunk in a storm in 1622 off the Florida Keys.

Not even the great wealth of the Indies could meet the tremendous costs of maintaining armies to safeguard and expand the Spanish Empire in Iberia, the Low Countries, France, Germany, Italy, North Africa, and the high seas. It is perhaps fitting that the Spanish Golden Age was both as brilliant and fleeting as the young empires it had destroyed in the Americas in its unrelenting search for gold.