Beginning in the 16th century, Protestants in France struggled in their rapport with royal power. Protestants owed the recognition of their rights more to sovereign decrees than to genuine tolerance or religious pluralism. The realization that the monarch held the authority to revoke what had been granted led to suspicion and mistrust toward rulers. Under Louis XIV of France (r. 1643–1715), they lost the rights gained under Henry IV of France (r. 1589–1610).

Edict of Nantes Undermined

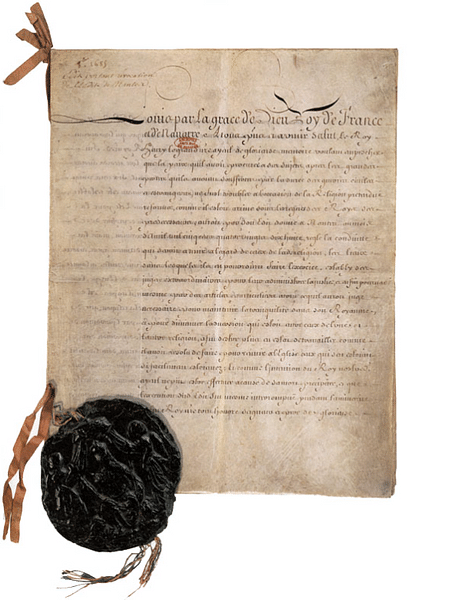

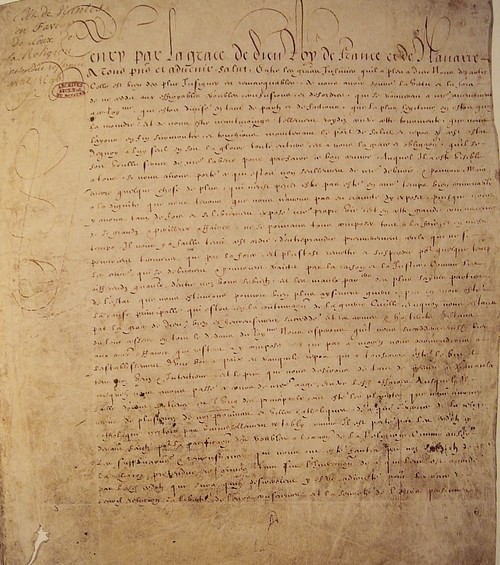

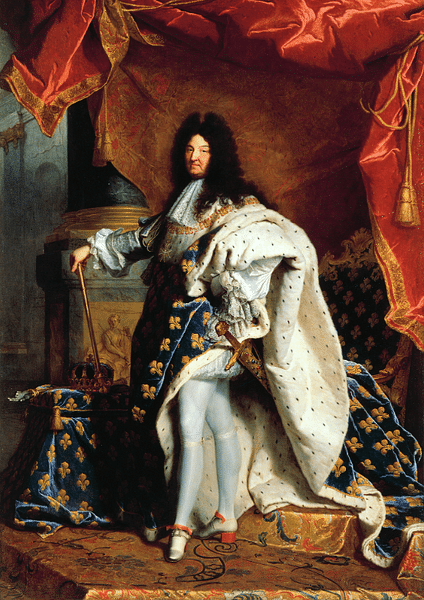

Louis XIV, known also as the Sun King (le Roi Soleil), was one of the most illustrious French kings. His reign was marked by cultural and military achievements as well as endless wars and religious intolerance. During the reign of his grandfather Henry IV, the effects of the Edict of Nantes in 1598 allowed French Catholics and Protestants to cohabitate in an uneasy peace. After the death of Henry IV in 1610, the Catholic Church and monarchy began plotting the removal of protections provided under the Edict of Nantes leading to its Revocation in 1685.

Early in Louis XIV’s reign, there was a season of religious tranquility for Protestants. With Cardinal Mazarin (l. 1601–1661) at his side, Louis XIV initially thought that strict respect for previous edicts and the refusal to grant additional rights was the most effective way to reduce the number of Protestants in his kingdom. Mazarin himself exercised tolerance in granting employment and government positions to Protestants, and he did not give satisfaction to the complaints of Catholic clergy who protested the construction of Protestant temples. A royal declaration in 1652 recognized Protestant fidelity to the Crown and promised the maintenance of the Edict of Nantes with the enjoyment of all its benefits. In 1656 this declaration was revoked and the exercise of Reformed religion was forbidden in places where it had recently been established. Provincial synods sent a delegation to present their grievances to the king who authorized them to hold a general synod in November 1659 at Loudun. The king’s representative reproached the Protestants in attendance for their insolence and announced that this would be their last general synod.

After the death of Mazarin, Louis XIV was determined to become the absolute master of his kingdom. With hostile measures, he sought to paralyze Protestant vitality and bring about conversions to Catholicism. The king reinstated the Commissions as the principal means of repression through which he sent commissioners into the provinces to investigate reported or supposed violations of the Edict of Nantes. Reformed churches were placed in an accusatory posture and had to justify their existence while Catholic Church representatives argued systematically for the closure of Reformed churches. Dozens of churches were forcibly closed in the provinces of Bas-Languedoc and the Cévennes where there were about 140,000 Protestants, or religionnaires as they were called.

Edict of Nantes Revoked

The conflict became more bitter beginning in 1679, and the legal insecurity of the 1660s and 1670s was replaced by measures to dismantle Protestant churches and intensify repression. Catholic conversion to Protestantism was banned, and Protestant converts to Catholicism were forbidden to return to their former religion. Louis XIV no longer sought to undermine the Edict of Nantes but was now determined to bypass it. The king unleashed the ferocious dragonnades which constrained Protestants to lodge the king’s troops (dragons) to accelerate conversions. In a matter of only a few years, the Protestant situation in France radically and perilously reversed. The Reformation had been solidly rooted in many provinces by the middle of the 17th century. Reformed churches had benefitted from favorable conditions created by the Edict of Nantes. Churches and synods had been well organized, led by quality leaders, and demonstrated loyalty toward royal power. Now the most prominent temples were demolished and the number of Protestant adherents dwindled.

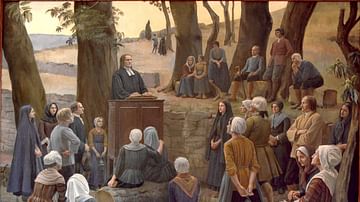

The prohibitions were multiplied: Protestants were forbidden to congregate outside their authorized places of worship and permitted to worship only at specific times; they were forbidden to sing the Psalms during worship; pastors were forbidden to stay in one place for more than three years; marriages between Catholics and Protestants were forbidden; ceremonies of baptism or marriages were limited to twelve persons; burials were forbidden during the day and only ten persons allowed to gather; pastors were forbidden to criticize the Catholic Church in any way, and they were forbidden to receive new converts into churches under threat of banishment and confiscation of property. Those hospitalized were pressured to convert and visited by magistrates to obtain a renouncement of Protestantism. Most Protestant schools were closed and parents were not allowed to send their sons abroad for studies. Little by little, Protestants lost virtually all the rights granted by the Edict of Nantes.

Catholic clergy persuaded the king that the success of these measures had diminished the Reformed religion to the point where few Protestants were left in France. When he discovered otherwise, the clergy lay the blame on the obstinacy of the Protestants and the inability of priests to combat the heresy. Louis XIV finally yielded to the clergy’s pressure to obtain the revocation of the Edict of Nantes on 18 October 1685, also known as the Edict of Fontainebleau. The king’s subjects were compelled to adopt the religion of the king.

Articles of Revocation

The articles of the Edict of Revocation reveal the drastic measures undertaken to remove the Protestant religion from France. Article one ordered the demolition of Protestant temples. Articles two and three forbade all religious assemblies with the threat of prison. Articles four, five, and six ordered the expulsion within 15 days of all Protestant pastors who refused to convert to Catholicism and the inducement of lifetime pensions for those who converted. Article seven outlawed Protestant schools. Article eight obliged all infants to be baptized into the Catholic Church and receive religious instruction from village priests. Articles nine and ten ordered the confiscation of possessions of those who already emigrated unless they returned within a specified period and forbade Protestant emigration under the threat of galleys for the men and imprisonment for the women. Article eleven stipulated punishment for new converts who refused the sacraments of the Church. Article twelve granted the right to remain in the kingdom to not-yet-enlightened Protestants conditioned by the interdiction of assemblies for worship or prayer. The Catholic Church opened centers of conversion (Maisons de conversion) and Protestantism no longer had the right to exist in the kingdom.

Conversion & Confiscation

The fear of the dragons led to waves of conversions among entire villages and accelerated the disappearance of the Protestants. In only a few months, hundreds of thousands of Protestants converted to Catholicism. They were called N.C. (Nouveaux convertis or Nouveaux catholiques), and were placed under strict surveillance. From 1685 to 1715 over 200,000 Protestants escaped and emigrated to places of refuge including Geneva, England, Germany, and Holland. Among them were soldiers, sailors, magistrates, intellectuals, merchants, and craftsmen whose departure impoverished France and enriched her neighbors. Of the approximately 780 pastors still in France in 1685, 620 left in exile and 160 abjured, although some later returned to the Reformed faith.

The Revocation reestablished the union of the Church and monarchy and provided material benefits for the monarchy. Before the reign of Louis XIV, Anne of Austria (l. 1601–1666), the wife of Louis XIII of France (r. 1610–1643), lived lavishly and had accorded privileges and monopolies to her admirers and sycophants. Louis XIV inherited the debts which weighed heavily on court finances. Over 600 Protestant temples were ransacked and destroyed. The Jesuits suggested that the plunder be given to the king. The possessions of individuals were targeted as well for distribution among the king’s loyalists, religious and otherwise. With the population decimated by periodic famines and dying of hunger, Louis XIV left the royal palace at the Louvre in Paris and settled at Versailles in 1682 surrounded by his court. Versailles became his principal residence and was expanded and embellished at exorbitant cost, the ostentatious symbol of his power and influence in Europe. There he and his courtesans reveled in sumptuous living off the proceeds of confiscated possessions. Counted among the beneficiaries were abbots and bishops of the Catholic Church, unashamed to profit from the plundering of Protestants, now fugitives and exiles.

Exile

40% of Protestants in the northern provinces of the kingdom crossed the borders of France to find safety, while only 16% in the Midi and 2% in the Cévennes fled the country. The majority of those who remained, two-thirds of Reformed believers, did not convert to Catholicism and began to organize themselves, first in small groups and later in large assemblies in out-of-the-way places. Less than a month after the Revocation, the Edict of Potsdam under Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg and Duke of Prussia, encouraged Protestant refugees to relocate to Brandenburg and granted them the same rights and privileges as those born there. The losses to France following the Revocation went beyond the loss of money and people. As fragile and complicated as the peace had been since 1598, the societal benefits of stability were real in creating schools and businesses. When Louis XIV began to shrink the Protestant space, those gains were sacrificed and France lost any hope of peaceful coexistence.

Conclusion

The Revocation of the Edict of Nantes offered a façade of unity. Through state violence, France falsely believed she had rediscovered spiritual unity. Historians rightly observe a connection between the religious terror of 1685 and the revolutionary terror of 1793. In 1685 Louis XIV treated the cursed Protestants as outlaws. One hundred years later the French monarchy and the French clergy paid dearly for their tyranny. The victors of the Revocation became the victims of the Revolution. Louis XVI of France (l. 1754–1793) and his family were massacred by their subjects. Priests were forced into exile and found refuge among the descendants of those whom their predecessors had persecuted.

Paul Deschanel (l. 1855–1922), deputy of Eure-et-Loir and later president of the French Republic, called the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes one of the greatest crimes ever committed against human conscience. The religious persecution of Protestants following the Revocation has made them the representatives of the great cause of freedom of conscience. Their repeated requests for justice and their oaths of allegiance to the Crown all failed at the foot of the throne of despots. Only in 1787 with the Edict of Toleration would French Protestants be considered fully French with the right to marry before a civil official, register the birth of their children, and bury their dead. Full recognition for Protestants as truly and legally French would come only with the much-maligned French Revolution in 1789, and Protestant equality with Catholicism was finally achieved under the Napoleonic Concordat and Organic Articles in 1801 and 1802.