The Spanish conquistadors might have gained a lasting reputation as the great gold-seekers of history, but they were actually far more successful in acquiring silver. Over 100 tons of gold were extracted from the Americas from 1492 to 1560, but the quantity of silver ultimately shipped in the treasure fleets back to Spain dwarfed that figure. By 1600, 25,000 tons of silver had been transported to Spain.

The process of acquiring silver had two phases. First, the conquistadors stole whatever they came across of value, kidnapping and torturing anyone they thought had knowledge of the whereabouts of valuables. The second phase was to investigate the source of the metal, that is to find and expand through forced labour the silver mines American rulers had themselves been exploiting. Mines like Potosí in Bolivia proved to be so lucrative that silver soon far outstripped gold as the most valuable cargo of the Spanish treasure fleets that shipped the resources of the Americas to Europe.

Properties & Supply

Silver was esteemed by many ancient cultures because of its relative softness, which made it easy to work by metalsmiths, and the fact that when polished it gains a lustrous shine. Silver was mined in ancient Mesoamerica and South America and was much valued by the Aztecs, Incas, Moche, Wari, Lambayeque, and Chimu cultures, amongst others.

The Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Americas in the final decade of the 15th century, and they were most interested in finding gold since it was much more valuable than silver – 1 oz of gold bought 11 oz of silver in Amsterdam in the 16th century. Silver was a good second prize, though. The early conquistadors plundered whatever artefacts they could of silver and melted them down to create coinage and bullion bars for ease of transport and sharing out between them. Indigenous people were mercilessly robbed, captured, and tortured to find out where their silver and other valuables were hidden. Countless works of art, often of high religious significance to the indigenous peoples, were lost forever in this ruthless quest for cash. When the silver items ran out, the conquistadors turned their attention to the source: the mines. These they found and further exploited while new mines were also located. Eventually, thanks to the massive yields of the silver mines in Mexico and Bolivia, it was silver and not gold that dominated the meticulously kept pages of Spanish colonial accountants. By 1540, silver made up over 85% of annual precious metal shipments to Spain.

The Silver Mines of Mexico

In Mesoamerica, silver was a valuable material, although not perhaps as much as gold, turquoise, and jade. The Maya, for example, had no source of the metal of their own in the lowlands. In 1547-8 the Zacatecas mines in Mexico began operation under Spanish control, the rich local vein of silver having already been mined on a smaller scale by the Zacatec people. The man who first supervised the mining was Juan de Tolosa, and he became the richest man in New Spain as a result. Guanajuato in central Mexico (opened in 1550) was another highly profitable mine. To better exploit silver-bearing ore, deep shafts were required along with extensive drainage channels, a labour-intensive process that required a serious investment. As the historians D. A. Brading and H. E. Cross note, "To construct a deep shaft cost as much as to build a factory or a church" (549).

A second round of spending was required to refine the mined ore. A mine like Sombrerete had no fewer than 84 stamp mills (arrastres) to crush the ore and 14 furnaces to smelt out the silver. Fortunately for the Spaniards, there was, at least, a spread of knowledge on how to most efficiently mine silver from other European experts (especially German miners) and from such published works as G. Agricola's 1556 De re metallica. Methods using an amalgamation process involving mercury were employed, but still, the yield of silver from ore was relatively low compared to later periods, on average 1-2 oz per 112 lbs (28-56 g per 50 kg). It was not uncommon for up to 30% of the silver to remain unextracted from the ore.

When the mine owner had finally got his silver bullion bars neatly stacked and ready for transport, he next had to give the Spanish Crown one-fifth of them. Bars were taken to the local royal representative, who stamped them ready for shipping back to the king in Spain. The same 20% tax was applied on silver in South America.

The Silver Mines of South America

For the Incas, silver was thought to derive from the tears of the moon goddess Mama Kilya. She had a magnificent temple dedicated to her at the Inca capital Cusco, which was covered with sheets of beaten silver. The thunder god Illapa brought rain and storms, and the lightning, it was thought, came from him flashing his silver robes. For this reason, mountains which were mined by the Incas for precious metals like silver often had shrines as they were considered sacred places or huacas.

The Potosí mines in the Andes at Cerro Rico, Bolivia, were discovered in 1545 by Diego de Huallpa, and they proved to be the single most spectacular source of wealth for the Spanish in the whole of their empire. At their peak around 1600, the Potosí mines numbered over 600, and they collectively yielded some 9 million silver pesos each year, more than all the silver mines then operating in the world combined. The motto on the coat of arms of Potosí was boastful perhaps, but entirely accurate: "I am rich Potosí, treasure of the world, king of all mountains and envy of kings" (Sheppard, 89). The Potosí mines became such a synonym for wealth they lent their name to other mines in the Spanish Empire, notably the San Luis Potosí mines in Mexico (established in 1550). There is, too, the still-used expression in Spanish, vale un Potosí, meaning "that's worth a fortune."

By 1600, Spanish America produced ten times the quantity of silver then mined in Europe. Production kept rising through the 17th century, but as veins were steadily worked out, by 1700 the existing silver mines produced only a quarter of the silver per year they had yielded a century before. Thanks to new mines elsewhere, though, and greater investment in the mechanisation of mining and better understanding and availability of explosives, the overall silver production in the Americas increased again in the 18th century.

The labour that extracted silver from mines was forced in the encomienda license system, which gave its holder the right to use local labour for free in return for offering a nominal degree of security and the "opportunity" to be educated in the Christian religion. As the Spanish state took one-fifth of all precious metals from the Americas, so the total exploitation of labourers was not discouraged. However, as diseases and poor working conditions eventually took such a severe toll on local populations, a rethink was needed. The encomienda system was consequently replaced by one of low pay, the repartimiento system, called the mita system in the South American colonies. African slaves were also brought to work in the mines; over 100,000 slaves were shipped to Mexico alone between 1521 and 1650, largely to make up for the shortfall in native labourers as the Americas became steadily more and more depopulated.

Mines like those at Potosí caused the growth of cities around them to house those who toiled for the Spanish overlords. By 1600, Potosí, despite its elevation of over 13,000 feet (4000 m), had a population of 160,000. Potosí's Spanish-speaking population was the largest in the Americas, and the city became infamous for murderous feuds between the Europeans. Despite its wealth and ability to attract people, Potosí's remote location, altitude, and frontier dangers meant that the Spanish colonial government never selected it as a centre of local government or trade. The silver was transported on to blossoming ports like Buenos Aires on the Rio de la Plata, so named for the silver (plata) that was carried on its waters. Potosí's fate was to remain a large shambling shanty town that thrived only as long as the veins of silver held out.

Such was the massive number of labourers involved in mines like Potosí that whole industries sprang up to support them, like coca production (the leaves were chewed to make the terrible underground conditions bearable for the miners). Ranches sprang up to provide the meat for workers and the mules to transport mined ore and refined silver. Then again, so much wheat and grain were demanded in these industrialised areas that surrounding rural areas suffered famines. To extract more silver, mercury was used in the process from around 1560, further deteriorating the working conditions of the mines, which were widely described as the "mouth of hell," spitting out silver but swallowing countless victims. The mita system was not abolished until 1821.

The Flow of Silver to Europe & the Philippines

A not insignificant amount of the silver mined in the Americas stayed in the Americas. As more and more Europeans settled in cities, particularly the capitals of Mexico City and Lima, so more silver was needed to buy imported goods and for the elite to establish themselves in an increasingly industrialised environment. Even if they owned the land and encomiendas around the mines, the elite preferred urban life, and so the silver found its way back to enrich the cities of Spanish America. However, the very raison d’être of the empire was to extract wealth from colonies, and so the bulk of the silver mined was sent back to Spain.

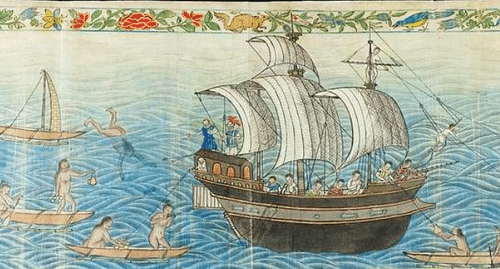

The Spanish galleons that carried this wealth operated in annual treasure fleets that were loaded with so much silver they were widely called the plate fleets, (a corruption of the Spanish plata), even if they carried all manner of other valuables from emeralds to pepper. Portobelo (aka Puerto Bello) on the isthmus of Panama was the first major collection point for silver taken from the Potosí mines. The silver was sent by Spanish galleons to Panama on the western coast of the isthmus and from there overland by mule train to Portobelo (which had replaced Nombre de Dios in this capacity in 1596). The Englishman Francis Drake once described this corner of the Spanish Empire as "the treasure house of the world" (Cordingly & Falconer, 15).

Huge quantities of silver also crossed the Pacific Ocean in the Manila galleons that returned to Spanish colonies in the Philippines (1565-1815). These galleons had brought valuable trade goods like spices and silk to the Americas, goods which were then shipped on to Europe. The silver was sent back to the Philippines to be used to buy the goods for the next voyage to the Americas. At their peak, each Manila galleon carried an average of 3 million silver pieces of eight per trip.

The massive influx of American silver and gold to European markets caused hyperinflation, not then a concept understood by many economists. Prices of commodities increased by 400% over the 16th century, and Spanish exports suffered as a consequence when wages rose to match. In addition, the Crown frittered away its precious metals, usually to secure loans from bankers long before the annual Spanish treasure fleets had even arrived in Europe.

The so-called second wave of Spanish silver of the 18th century was better managed and helped improve Spain's fortunes again. As the historian J. H. Parry notes:

The flow of silver steadily increased; it irrigated the economic soil of Old and New Spain, and enriched Cadiz and Barcelona. Together with the gold of Brazil, it helped to finance the early industrial revolution of northern Europe; and since the highest demand for silver was felt, and the highest prices paid, in the Far East, it helped also to finance the commercial and military operations of the East India Companies, and to quicken European maritime trade all around the world (313).

The silver that was destined for the safe deposit boxes of the government and wealthy investors in Spain had first to run many risks. Smugglers were keen to syphon off silver bars before the state could claim its tax levies. Corruption was rife amongst the accountants at the mines, those in charge of the silver's collection and transport to key ports like Acapulco, Panama, and Buenos Aires, and the silver masters who were responsible for its shipment across the Atlantic.

Then there was the threat from the sea - the buccaneers, pirates, and privateers of all nationalities who were keen to intercept the Spanish galleons as they sailed the Atlantic. In 1579, for example, Francis Drake captured the Nuestra Señora de la Concepción off the coast of Peru, which was taking treasure that included 26 tons of silver bullion. In 1628, a Dutch force of 31 ships led by Admiral Piet Pieterszoon Hein (1577-1629) captured the entire New Spain treasure fleet on its way to Havana. Hein managed to seize 46 tons of silver and many other valuables besides. Storms were an even greater threat and accounted for many wrecks like the Nuestra Señora de Atocha, which was carrying a cargo worth $400 million, which included 20 tons of silver when it was sunk in a storm in 1622 off the Florida Keys.

Still, the silver kept coming despite these difficulties, and the Spanish Crown was so enriched it became overconfident in the constancy of its supply and its military capabilities, stretching the empire beyond its limits so that it reached a tipping point of neglect and underfunding. Even the riches of Potosí could not meet the enormous costs of raising Spanish armies across Europe, especially when they were defeated armies. By the mid-17th century, the empire had long attracted the covetous eyes of other European nations eager to sweep in and challenge Spain's dominance. States like France, the Netherlands, and Britain, who were now building their own lucrative empires, used their powerful and more modern navies with devastating effect to reshape the world map, both Old and New.