In this interview, World History Encyclopedia sits down with author James Lacey to chat about his new book Rome: Strategy of Empire published by Oxford University Press.

Kelly: Can you tell us a little bit about your background?

James: Sometimes when people ask me for my background, it sounds like I can't keep a job, but I'll go through it from beginning to end. I spent about a dozen years in the United States Army as an infantry officer, on active duty, that was the 82nd Airborne, 101st Airborne. A lot of time in Germany after that at various senior army headquarters, then got out when the Russians took all their toys and went home. I thought that was the end of things, but I didn't realize the amount of excitement we would have in the post-Soviet era. I did retire from the reserves, I went and worked on various jobs in the Wall Street area, Wall Street, for another dozen years, and my office on 911 was on the 82nd floor of the World Trade Center. I got home that night and said, I'm going in another direction. I've left the army, started in the business world, and now I'm going to go to my first love of writing and history.

I got a job writing editorials for the New York Post and the New York Sun. A week later, I was talking to the editor of Time magazine at lunch. I said, I'd like to come to Time, and he said, sure. So, I went over to Time magazine, which sort of seems to annoy a lot of journalists who spend their entire life trying to do something like that. Operation Iraqi Freedom was gearing up. I said I wanted one of the embed jobs, they said all the embeds were going to the Washington bureau and they couldn't get any more. I said I can get my own. I still had a ton of army contacts and said, you get your own, you can go. So, I embedded back into the brigade. I had been a company commander and the brigade commander and I had been company commanders together, so that was an interesting experience. Then I came back and decided to write a book on the war. Rick Atkinson beat me to it on the unit I was with. So, I went to do some more research and that led me over to the Institute of Defence Analysis, a think tank that supports the military. Stayed there for about seven years doing research on several strategic topics and writing on a number of strategic topics.

I got my Ph.D. while I was there in history. I only did it really for one reason which was to teach history. A job came open at the Marine Corps War College, my Ph.D. was all eight days old, they hired me, and I've been there for about twelve years. I've had an eclectic series of experiences. For writing this book, it's great. There are a lot of people who studied Roman history, which is in many regards military history, who don't understand how militaries work. How armies, how soldiers and officers think. So I had decades of that experience to bring into this. Then there's a lot more to strategy than just the military side. I understand how the global economy works. It's part of my job. My Ph.D. was actually on the economics of World War II, so bringing the economics, the military and other things together let me tell a story that really hasn't been told ever. Edward Luttwak wrote The Grand Strategy in a Roman Empire, but he only went up to the third century and didn't cover anything after that. There were still another 200 years of the Roman Empire to go before the Western Empire collapses.

I said, when I'm doing this, I'm going to cover the whole thing. All he covered was basically the military structure of the empire. Rome didn't lose its empire because its soldiers stopped fighting. It lost its empire because it took the eye off what truly mattered, its economic core, and it couldn't buy any more soldiers. There were plenty of soldiers out there to buy, Rome just couldn't afford them anymore. So, taking my varied jobs together gives me a perspective that I think is missing from the entire debate on whether Rome could have a strategy or not.

Kelly: Your book, Rome: Strategy of Empire, you would say is focused on the strategy of the military for the whole history of ancient Rome.

James: It's not limited to the military. You can't talk about Roman strategy without having some focus on the military aspects. But I spent a lot of time on the economics that backs it up, Roman diplomacy, which is very important, the infrastructure of Rome, and transitions of government. There's a whole bunch that goes into creating a strategy. The simple solution, ways and means. What do you want to do? How do you want to do it, and then what do you have to do it with?

The really crucial reason I decided to take this on, is I've been reading about Rome my entire life, I'm a professional historian, but I'm an amateur Roman historian. I've read tons of books. I've read almost all of the classic material. But there's a huge number of professionals, ancient historians who have specialised in Rome since the very beginning, who know every bit of the material perfectly. And when Luttwak wrote his book, he hit a topic that none of them had really ever thought about before. Did Rome have a strategy? It seemed to me that Luttwak was like a virus. You're a strategist, you do military advising and consulting. You don't know anything about Rome, and you, therefore, got it all wrong. That is the incredible consensus opinion of ancient Roman historians. There are exceptions and some very big exceptions. Cambridge's ancient histories have been all redone in the last couple of decades, and they basically have a chapter saying Rome was incapable of strategic thought. Not only did they not have a strategy, but they also couldn’t even think strategically. That just bothered me. To say that when you realise Rome spent over half its revenues on its military, navies, legions, all the fortresses all along the perimeter of the frontier. It means they were spending 50% of their GDP or close to it every year on a strategy to keep what was on the other side of the frontiers on that side. Not letting them into the Empire. Nobody in 500 years stopped and said, why are we doing this, or are we doing it right? From just a commonsense perspective, that struck me as wrong.

I had a chance to write a chapter in a book. That chapter was almost as hard to write as a book because I hadn't dug deeply. I just assumed Luttwak got it wrong because everybody had told me he did. Then I started researching the chapter and I thought, Luttwak got a lot of this right. His book The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire is 40 years old. In my opinion, he over-systemised his analysis and he doesn't tell you why they did things. He says, here's what they did and that's strategic, and they must have had a strategy. But you really don't get what was driving that strategy. Why did they make these decisions this century, and new decisions in the next century? What was changing over time? 500 years of empire, it wasn't an empire in stasis. Things didn't move as fast as they move in the 21st century. But 500 years. If you go back 500 years from today, Henry VIII is still on the throne of England. Copernicus is just discovering that the sun might be the centre of the universe. That is a lot of time for change. Rome changed, the empire changed, and their strategy changed over time.

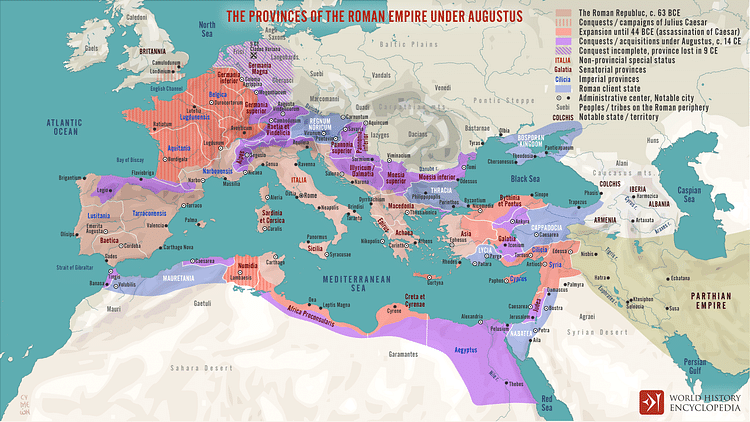

But Roman historians themselves say, hey, Rome didn't even understand the geography of the world or its empire, so if you don't understand geography, how can you think about strategy? This has probably been overanalysed to death, the fighting, and the warring, back and forth, what they knew about geography, what they didn't know about geography. It may have gone too far, that analysis, that debate, but they seem to have concluded that they didn't understand much geography and what parts they did was not enough to form a strategic conception that they could execute on an empire-wide basis. The basis of that was the maps that we currently have for them are what they call itineraries. They look like train maps, like the subway if you've been to New York or London train maps, it's stop, stop, stop. You don't know anything about what's in between. It's just a series of stops. Historians have said that you can't plan a strategy based on how many days it takes to go from Rome to Ravenna, then Ravenna to Vienna, Vienna, to wherever you want to go, because that's all this was. They were like travel logs. If you leave Rome today to walk to Ravenna, it will take you 16 days, and there'll be a little line from Rome to Ravenna, which may be half an inch away or ten inches away. They didn't care about that space, and they would just write the number on the side of the line, 16. Then you knew it took 16 days to walk that distance.

Roman historian consensus is that you can't use itineraries to do strategy. I thought, well then you better tell US 21st century strategists to stop doing that, because that's exactly what we use. They call it nodes. Now, instead of points on a map, it's various nodes, railroad nodes, and seaports. The only time the military cares about the geography on a map is at the point of the spear where they were actually fighting. So, all the Romans cared about was, all right, I got 30 legions, eight of them, along the Rhine River. I'm going to pull four out from four cities, and I'm going to move them to Antioch. Then they take out the itinerary, it's a ten-day march from this city to that city, six days in this city, and immediately they knew exactly how long it was going to take to march 1 legion in that city. The only execution thing you now have to do is send messages ahead to the governors of the provinces.

The itineraries, rather than being incapable, something you would never use to do strategy, turned out to be exactly what you need to do military strategy. That alone throws out 90% of the argument that the Romans couldn't do strategy. There are war games out there you could buy for fifty or a hundred dollars that are based on the Roman Empire, and every one of them is point to point. It's like a hub and spoke network because that's how you think about strategy. What I'm adding to the field is, you guys have done an excellent job telling me what happened in Roman history. I'm standing on the shoulders of giants, and I list them in my book. I'm taking all of your knowledge that you have built up over 200 years, and now I'm going to overlay upon it the stuff I do know about strategy, the economics of war, and how we think about these things in the current era, because strategy never changes.

Kelly: It's incredible that even just one facet of modern strategy, modern military, that, you know already could make such a huge difference to your understanding of strategy in the Roman Empire.

James: I wasn't doing this as a lessons learned book, but strategy doesn't change if you are deeply imbued in strategic thought. What the Romans did, what Napoleon did, and what we do today can all be summed up into certain categories. They always say the nature of war never changes but the character of war may change, and the technology may change. Here's an interesting thing. Rome, if it went beyond the edges of its empire, it could send out about 50,000 troops and maintain them for a bit of time. If it wanted to make a major push, it could get 150 or 200,000, but it couldn't sustain that. The economy of Rome could not sustain that level of force outside of the empire for an extended period of time. Those numbers never change.

The number of troops at the front end of the sphere has not changed since ancient times. The cost has gone up, but relative to GDP, it's about the same. If you're looking at Roman strategy and you understand it, you can use that context to think about the US strategy or Chinese strategy or anybody's strategy today. There are certain overriding lessons. One, keep your eye on what's truly important. Rome never lost its core principle. Everything outside on the edge of empire, we have this frontier. It's not a line, it's like a zone, but everything on the other side of that is probably very bad, and we should not let it in. And if it gets in, the most important thing is we must protect our economic core, and then we can win. No matter how many setbacks we have, if our economic core remains strong, we can make a comeback. Until the end, they never really lost sight of those principles.

I did have one thing that got in the way repeatedly, and if they could have figured it out, Rome might still be, for all we know, and that is smooth government transitions. They never got it right. The Roman Republic collapses because the legions of Rome became loyal to the person who was paying them, which was their generals. They were no longer loyal to Rome itself. So, you have a brutal civil war, and then we have the empire, and the legions now swear loyalty to the empire. The most dangerous thing you could be in the empire, in my opinion, is a successful Roman general, because as soon as you were successful, you become a threat to the emperor. You might get those legions behind you and march on Rome. There was good reason for that, because, over the course of 500 years, that happened on multiple occasions. When a general rose up and said, I'm in revolt, it didn't matter what strategy Rome wanted to do, what threats were on the outside trying to get in, everything else went to second place because the overriding strategic concern was, I have to beat the usurper. And the Roman legions would march, and they would fight. If Rome could have avoided these bloody transitions, these bloody civil wars that happened on a recurring basis, there was no power outside the frontiers that could have taken on Rome. Even the Huns could not have taken on a Roman empire that was solidified under one rule and ready to meet them in open battle.

In the third century, with crisis after crisis, it's the beginning of a climate crisis, temperatures cool, and there are plagues. The barbarians are moving on all fronts. The Persian empire, which was the Parthian Empire for a number of years, the Parthians have been replaced by Sassanids, who are a lot more active, a lot more military oriented, and they're looking to expand themselves. The easiest way to expand was into the Roman Empire. It looked like Rome was going to collapse. They lost all of Gaul, which is mostly modern-day France. Egypt was lost, and the Empire was collapsing, but they maintained that core. Italy, North Africa, the Danubian provinces, the economic centre, and the place where you do the best recruiting were in the Balkans. And they come back, they fight their way back, they have another 200 years of life. But then in the final crisis of the early fifth century, they all come across the border, and you finally have Attila bringing the Hun in. The Romans sort of focus on Attila and these vandals, maybe 10 to 15,000 warriors at most get into Spain. They spring across the Gibraltar straits there and get into North Africa. A couple of years later they own all of North Africa. That is the economic centre of the Roman Empire. Once it was lost, Rome finally looked up and said, who cares about the damn Huns? We don't care anymore. We got to get that back. They were not able to do it. The Byzantine Empire eventually got that back, but it was a wasteland by then. Rome has lost its grain. Rome's fleets were in North Africa. The Roman tax base was North Africa. They lost everything.

You don't see that in the Eastern Empire, which has a much longer life because the barbarians can't make the jump on Constantinople. The Eastern Empire's economic core, which is all of the Levant, all the way down and into Egypt, which is the richest province in the Empire, is never touched until the Arab invasions coming up from the south. If Rome can control its economic core, they were close to invincible. They took their eye off the ball and said, boy, these Huns look dangerous, we're going to focus on them and then they lost North Africa. Their time was up.

The financial spine of the Empire was cracked, and we can't lose track of how important that was. The Roman Empire is incredibly rich compared to the Roman Republic because the Roman Empire gets richer almost every year. Prior to the Roman Empire, the Pax Romana, the Mediterranean is just a war zone. Wars everywhere, city-states fighting city-states, small provinces and small states fighting each other. Rome came in and said, first you fight us, we win. You don't fight anyone anymore. I mean, even when Rome wasn't conquering you their power was so great.

But think about this in economic terms. If you were a farmer and you built yourself a nice irrigation system and a nice mill, and you were making some money from the other farmers who brought their grain to your mill, and a war happens, runs right over your territory, they wreck your mill, they ruin your irrigation system, the war is over. Do you rebuild it? In a state of constant warfare? You might, but even then, at great expense, you rebuild everything, but you haven't made any progress. You just got back to where you were before the war. Then another 20 years later you think, wow, I'm starting to make progress, maybe I'll build a second mill. Oops. Now a war starts. Now you have the Pax Romana. 500 years of peace in the core of the Roman Empire. Legions may have been fighting all the time on the frontiers, but the whole core of the Roman Empire is at peace.

We can't understand the Romans today. Us trying to think about how to think like Romans is literally impossible. Even their enemies, the barbarians, the savage barbarians, would look at a Roman battlefield afterwards in disgust and be sickened. That savagery. Because the Romans didn't just kill you, they chopped you up, and threw your entrails everywhere. It was a feast of blood and gore. What's the number one sport? Well, let's go watch the lions eat Christians or anybody else that the lions feel like eating this time of year. They have a completely different mentality from us. There's no sentimentality in a Roman family. A Roman father has the power to kill anyone in his family, and no one would question it. He is God in his family. This is the kind of mentality you're with. But it's a violent time, and it takes that kind of violent people to say, everyone stops fighting. If you really want to have a fight, you gotta come through us. And they said we don't want to go through them. But now think if you're, a farmer. I'm going to build a mill, I'm going to build an irrigation system, I'm going to build storage facilities, and they're going to last forever because no one's marching through to destroy it. This leads to a huge amount of economic growth. The military side of the Empire becomes easier and easier to afford.

Kelly: Thank you so much for joining us today, it was great talking to you about your new book, Rome: Strategy of Empire.

James: Very nice talking to you too.