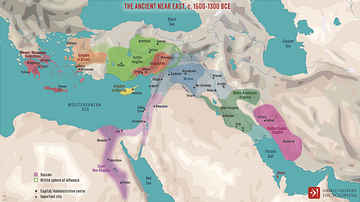

The ancient Near East was home to a multitude of civilizations, across Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Levant, each with unique views on medicine, conception, and women’s role in society. Attitudes towards contraception and abortion varied according to these beliefs. Both the oldest medical literature on performing abortions and the first known law against abortion come from the Near East.

Christianity and Islam–two monotheistic faiths which emerged in the Near East–have since become some of the largest religions in the world. As a result of their influence, the different streams of thought which emerged in the ancient Near East continue to shape modern law and medical ethics around the world.

Pregnancy in the Ancient Near East

The agricultural civilizations of the ancient Near East placed a high value on fertility, both in the land and its people. Most people hoped to have large families, with multiple children that could continue their traditions and support them in old age. Infertility in people was explained as physical or spiritual imbalances in the body while infertility in the land was considered a sign of divine displeasure, often aimed at the ruler.

These cultures were also highly aware of the dangers of pregnancy and childbirth, which were commonly attributed to supernatural causes at a time when medical knowledge was limited. This cultural anxiety is expressed across the religious, magical, and medical beliefs of the Near East. Threats to pregnant women and infants were personified by various demons and malicious deities associated with maternal and infant death.

In Mesopotamian mythology, the goddess Lamashtu was believed to cause death and miscarriage by touching the stomach of a pregnant woman. Similarly, the Kūbu demon, a manifestation of restless stillborn souls, was blamed for illnesses that took the lives of newborns. In Egyptian beliefs, miscarriages and irregular births were often attributed to the working of evil magic, restless spirits, and malevolent deities. These spiritual threats personified the fear and grief that sudden death brought into the community. It was also believed that malicious individuals, particularly sorcerers and sorceresses, might use magic against women and children.

Within this belief system, medicine included both practical treatment and magical cures. To protect women and children from harmful supernatural forces, they were often given amulets and other objects depicting protective deities. The Egyptian deities Bes and Taweret were popular protectors of pregnant women and children, as was the Mesopotamian god Pazuzu. These deities were depicted with fearsome features meant to scare away evil.

if (you want) sorcery not to approach a pregnant woman, (and) for her not to have a miscarriage, you grind magnetite, guælu-antimony, dust, åubû-stone (and) dried “fox grape.” You mix (it) with the blood of a male shelduck (and) cypress oil and, if you rub (it) on her heart, her hypogastric region and her (vulva’s) “head,” sorcery will not approach [her]. (Late Babylonian text, trans. by Scurlock)

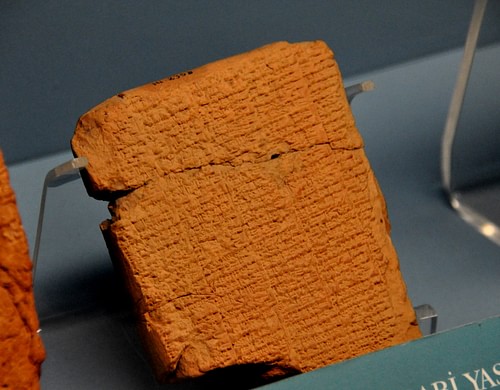

Over time, people in the Near East began to identify natural causes and practical treatments for common health issues. The importance of reproductive health is demonstrated by the number of Egyptian and Mesopotamian texts about it. The oldest surviving medical text from Egypt is the Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (c. 1850 BCE), which deals with a variety of women’s health issues, including fertility, menstrual issues, and contraception.

Medicine in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia combined empirical evidence with spiritual beliefs, and thus no distinction was made between practical and magical treatments. Women’s health issues were primarily treated by midwives, with physicians only becoming involved if there were serious complications.

Contraception

The notion that women could regulate their fertility through chemical means is as old as medical records. In practical terms, it means that the idea is older than the record. (Riddle, 66)

The history of contraceptive medicine stretches back to the earliest Near Eastern medical literature. Many methods of contraception described in ancient literature were ineffective, although some may have limited efficacy. The majority of surviving evidence for contraception comes from Egypt, which had a particularly rich medical tradition. Women in ancient Egypt also enjoyed considerably more freedom than women in many neighboring civilizations, which may have contributed to more relaxed attitudes towards birth control.

The oldest surviving description of a contraceptive in literature is in the Kahun Papyrus, which describes how to prepare a contraceptive suppository out of crocodile dung, saltpeter, and fermented dough. While unpleasant, crocodile dung and saltpeter may have been effective at blocking conception. The use of crocodile dung also had spiritual connotations, since crocodiles were associated with infertility, and excrement had symbolic uses in Egyptian medicine.

The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) recommends combining acacia and colocynth in a contraceptive suppository. Both of these plants have powerful contraceptive or abortifacient properties, although their toxic properties could also be lethal. Recipes for contraception are found in the Ramesseum medical papyri (c. 1850 BCE), the Carlsberg papyrus (c. 1500 BCE), and the Berlin papyrus (c. 1350 BCE). Among the ingredients used were honey, gum arabic, and natron. Another method of contraception known in antiquity was extended breastfeeding, and Egyptian women commonly nursed their children for three years. This method of contraception was common in many premodern societies, as it was believed to delay the return of fertility after childbirth.

Beginning of the prescriptions prepared for women to allow a woman to cease conceiving for one year, two or three years: part of acacia, carob or dates; grind with one henu of honey, lint is moistened with it and placed in her flesh. (Ebers Papyrus 783, trans. by Nunn)

Contraceptive plants were likely known to Mesopotamian civilizations, despite limited literary evidence for their use. Assyrian and Babylonian texts reference plants and molds which they understood to be abortifacient or contraceptive, although there is no direct evidence that they deliberately used them for those purposes. The Babylonian lexical tradition mentions a “plant of not giving birth”, which was likely prescribed to reduce fertility. By the Roman period, there is ample evidence of contraceptive use in the Near East.

Under Jewish religious law, women were permitted to use contraception while men, who were obligated to follow the directive to “be fruitful and multiply”, were not. The Talmud, a collection of texts on Jewish law compiled c. 200–500 CE, describes sterilizing draughts used to prevent pregnancy, and the use of wool sponges as a barrier to prevent conception. The former is explicitly permitted to all women, while the latter is permitted to those who are minors, already pregnant, or would risk health problems if they became pregnant.

In the early time of creation, in the time of Lemech, a medicine was known, the taking of which prevented a woman's conception. (Genesis Rabbah, 23)

Abortion

Compared to ancient Greece and Rome, information about medical ethics in the ancient Near East is scarce. As a result, there is limited evidence regarding attitudes towards abortion in these civilizations. The surviving evidence indicates that it varied considerably between cultures and periods, according to beliefs around the point at which life began. With the exception of Egypt, where men and women were relatively equal, women in the ancient Near East generally had fewer rights than men. Because of this, the ethics of abortion were not often considered through the lens of women's rights.

Because of how menstruation and pregnancy were thought of in ancient medicine, treatments intended to terminate early pregnancies were often not considered abortion. Gestation was considered to be a gradual process, in which a fetus developed into a child. For example, under Hebrew religious law, a woman was not considered pregnant until 40 days after the date of conception. Deliberately inducing a miscarriage before this point would thus not be considered abortion. Many ancient societies also made a distinction between viable and nonviable fetuses.

Various abortifacients were known to the ancient Egyptians, and it appears that there was no stigma against abortion. The earliest known literary reference to abortion is contained in the Ebers Papyrus. Most methods of abortion prescribed in the papyrus involve administering medicinal plants and other ingredients to induce miscarriage. These contraceptives were either consumed orally or applied topically. One recipe called for the ingredients to be burnt and their smoke used to fumigate the patient. It is unknown whether surgical abortions were ever performed in ancient Egypt, but it is unlikely as Egyptian physicians seem to have avoided gynaecological surgery.

References to abortive medicine are also extant in the surviving Babylonian medical corpus. Namruqqu, an unidentified plant, was prescribed to induce abortion. It was also used to ease labor when prescribed late in pregnancy, which has led some modern historians to speculate that the plant caused uterine contractions. One Babylonian text calls for namruqqu to be crushed and mixed into beer. The resulting concoction is then given to a pregnant woman on an empty stomach to bring about an abortion. More complicated recipes call for several medicinal plants to be mixed into beer along with a crushed lizard.

Little is known about legal and moral views on abortion in ancient Mesopotamia and the Levant. Historians generally agree that fetuses were not considered to be distinct entities with legal rights in the ancient Near East. Under the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1772 BCE) and Middle Assyrian law, a man who injured a pregnant woman and caused her to have a miscarriage had to pay a fine as compensation. If the woman died, he received a much harsher penalty for committing murder. Similar beliefs are held in the Old Testament. These laws make it clear that the loss of a fetus was not generally considered murder.

Almost nothing is known about the use of abortion or contraception in ancient Persia, except that the Avesta, a Zoroastrian scripture, strongly condemns abortion. Although Zoroastrianism was the official religion of the Achaemenid Persian Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) and the Parthian Empire (247 BCE - 224 CE), the empires were home to a multitude of religious beliefs and peoples.

Jewish views on abortion in antiquity were mixed but generally condoned abortion for the well-being of the mother. The Mishneh Torah, which was compiled in the 1st and 2nd Century CE, explicitly condones late-term abortion if needed to save the life of the mother. According to early Islamic texts, similar views may have prevailed in pre-Islamic Arabia. However, some Romano-Jewish authors such as Philo (20 BCE–50 CE) and Josephus (36–100 CE) condemned abortion, a position that influenced Christian thought on the topic.

Infant Exposure & Abandonment

Infant exposure, the practice of abandoning a newborn in the wilderness or a public place, is attested to throughout the ancient world, including the Near East. This practice was used to limit family sizes, and to get rid of unwanted or illegitimate children. Abandoning infants may have been preferable to infanticide because parents could avoid feelings of guilt, and hope that their child would be taken in by someone else. Children were also at times sold or given up into servitude, especially by unmarried women or families who could not afford to raise them.

The Biblical narrative of Exodus echoes similar themes, reflected in the story of Moses’ discovery in a basket after being placed in the Nile River by his mother. Infant exposure appears to have been less common in Egypt than it was in ancient Greece and Rome. The Greek historian Herodotus (c. 484 – 425/413 BCE) stated that unlike in Greece, the Egyptians never abandoned infants. His claim was likely exaggerated, but infant exposure does appear tto have been uncommon in Egypt until the Ptolemaic and Roman periods.

Conclusion

Egypt, Persia, Mesopotamia, and the Levant were heavily influenced by Greek culture during the Hellenistic period (323–31 BCE), and most of the Near East was under the control of the Roman Empire by the 1st Century CE. As these civilizations influenced one another, their views continued to change. The emergence of Christianity in 1st Century CE Israel marked an important point in the development of moral and religious thought in the ancient Near East. The morality of contraception and abortion had been debated by Jewish scholars and became a widespread controversy in the Christian community during the 3rd Century CE.

The use of contraception was scrutinized under Biblical beliefs that procreation was religiously mandated. While Jewish religious law had permitted women to use contraception in many cases, some Christian theologians felt that it was inherently sinful. This position was tied to the belief that sex was inherently sinful and should only be condoned for the purpose of reproduction. Many Church fathers also felt that allowing women to access contraceptives would lead them to act immorally.

Because the morality of abortion was not directly addressed in Christian scripture, it was widely debated by early Christian theologians. The crux of ancient debates around abortion focused on issues such as the point at which a fetus is considered to be a person. Jews and Christians living in the Roman Empire were heavily influenced by Greco-Roman culture in this regard, with many arguing that a fetus did not attain personhood until it had begun to develop, in keeping with Aristotlean philosophy and many Near Eastern traditions. Others, such as Tertullian (c. 155-220 CE), argued that human beings received souls at the moment of conception. Counterbalancing concerns about the potential personhood of a fetus, were concerns about the health of pregnant women for whom abortion could be life-saving.

For theologians such as Tertullian, the rejection of contraception and abortion was important as a point of distinction between Christians and polytheists. This position was accepted by many, but not all, church fathers during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Because of the diversity in religious thought, there was no singular Christian doctrine regarding abortion and contraception. However, the prevailing view in the Medieval Church was that abortion was prohibited, and this became the standard for Christians in the Near East.

After the spread of Islam in the 7th Century CE, Arab and Persian scholars considered the topic of contraception and abortion using similar arguments as Jewish and Christian theologians. While some Islamic jurists considered abortion to be forbidden, most permitted it, especially in early-term or medically risky pregnancies. In the diverse religious environment of the Medieval Near East, this was a continuing source of debate for Jewish, Christian, and Islamic scholars.

Christianity and Islam, both strongly influenced by the collective cultural and religious heritage of the Near East, have since become the largest religions in the world, with billions of adherents. These faiths have helped shape the legal traditions of many countries in the Middle East, Europe, Africa, and the Americas. In this way, attitudes towards family planning in the ancient Near East continue to shape ethical and social norms around the world.