The War of the Camisards (1702-1705) was launched by Protestant Huguenots in the Cévennes region of southern France. After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 by Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715), Huguenots worshipped illegally in secret places before rising up to reclaim their religious rights.

Return from Exile

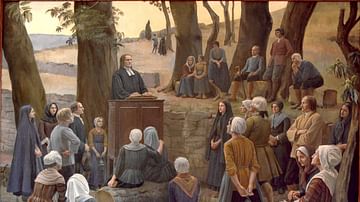

After the Reformed religion was outlawed by the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 under Louis XIV of France, Protestant temples were destroyed and pastors were exiled. The Huguenots saw themselves as metaphoric Hebrews and their leaders adopted names associated with the Jewish people of the Old Testament – Josué Janavel, Abraham Mazel, Salomon Couderic, and Élie Marion, among others. Huguenots in the Cévennes worshipped and wandered in the woods of this region. The preachers of the Cévennes were often considered seditious rebels working hand in hand with France's enemies to deliver the province to foreign powers.

Exiled pastors returned to the Cévennes in 1689. These men were united in their desire to reestablish Protestant worship and were bound by the conviction that state-authorized religion was not in conformity with biblical teachings. Among them was Claude Brousson (l. 1647-1698), perhaps the most famous clandestine preacher, who had self-exiled to Geneva and Lausanne and returned to France to preach and organize secret nighttime gatherings. He entitled his collection of sermons "The Mystical Manna of the Desert" (Janzé, 623). Another returnee was François Vivent (l. 1664-1692) who refused to renounce his faith in 1685 and was hunted down before being authorized to leave France in 1687.

Although Vivent, Brousson, and their companions returned to France to awaken the zeal of new converts, they also intended to join the coalition of William of Orange (l. 1650-1702) in the hope of confronting Louis XIV with a formidable insurrection. They received promises of support from England, Switzerland, and Holland. As attested in letters written by Pierre Jurieu (l. 1637-1713), Brousson, and others, the persecuted church sought above all the freedom to practice their religion – a freedom offered to them under Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610) and taken away by Louis XIV. Both Brousson and Vivent became martyrs; Vivent was killed in a cave defending himself on 19 February 1692, and Brousson was executed at Montpellier on 4 November 1698.

Prophetic Epidemic

On their return, Brousson and Vivent also addressed what has been called a "prophetic epidemic" (Krumenacker, 79) which was rampant in regions deserted by pastors. In the absence of pastors, prophets and prophetesses proliferated in Dauphiné, in Vivarais, and especially in the Cévennes. In the beginning, these self-appointed leaders preached the gospel, exhorted repentance, and promised freedom. In time, claiming inspiration from the Spirit and nourished by the Old Testament, many fell into mystical trances and preached revolt. Most Protestant pastors disapproved of their activities and attributed the excesses to the lack of spiritual guides. Early prophetic manifestations were peaceful until 1702. As arrests and executions increased, the prophetic message changed into a call to holy war and armed resistance.

War of the Camisards

The origin of the word 'Camisard' as a description for insurgents from the Cévennes region is disputed. According to some historians, they owe their name to the white shirt they wore over their clothing to be recognized among themselves. Others see a reference to the ancient word 'camisade' (night attack) or to 'camin', referring to paths along mountain ridges. Their numbers at any one time rarely exceeded 1,000 men, with a total of approximately 7,000-10,000 men engaged in combat during the war. Over 50 percent were younger than 25 years old, mostly from rural or semi-rural regions. Over two-thirds were artisans in textile; one-third were shepherds or farmers. The wives and sisters of the Camisards followed the troops and at times also wielded the sword. The Protestant nobility was largely absent, while some became active in the repression of their co-religionaries.

The war had its beginning in July 1702 when the prophet Pierre Séguier, called Esprit Séguier, declared during an assembly that the Spirit had called him to liberate prisoners arrested and tortured by the abbot of Chaila at Pont-de-Montvert. Accompanied by Abraham Mazel, Séguier and 40 men marched all night and surrounded the presbytery. They forced open the doors, freed the prisoners, killed the abbot, and set the edifice on fire. Emboldened by their success, they set fire to two churches and killed eleven Catholics. Three of the attackers were captured and tortured, Séguier among them, who was burned at the stake at Pont-de-Montvert. The Camisards wreaked havoc throughout the Cévennes under the leadership of Abraham Mazel, Gédéon Laporte, Jean Cavalier, and Salomon Couderc. They practiced the Old Testament law of the talion, destroyed churches in response to their temples burned down, and put fear in village priests who sought refuge in cities.

During their first military encounter in September 1702, Laporte and Cavalier faced off against soldiers led by Captain Poul. A month later, Laporte and several of his men were surprised in a ravine and killed, their heads exposed on the bridge of Anduze as a warning to the insurgents. Laporte's nephew Pierre Laporte, later known as Rolland, and Cavalier, sheep castrator and shepherd respectively, led small groups of poorly armed peasants for two years in guerrilla warfare against the king's troops. The success of the Camisards was partly due to their knowledge of the rugged countryside with its woods, ravines, and caves. They had the complicity of newly-converted Catholics and were feared by other Catholics. They held frequent worship gatherings and sang Psalm 68 "Let God arise" before attacking the enemy with fury. The royal troops often fled at the intonation of the first notes of the Camisard hymn.

In December 1702, the Camisards addressed a letter with their demands to Victor-Maurice, Count de Broglie (l. 1647-1727), commander of the royal forces. They wrote that they simply wanted the freedoms purchased with the blood of their ancestors and that they were prepared to die rather than renounce their beliefs. Because the edicts of the king had deprived them of their right of public assembly to worship, they had withdrawn into the mountains and caves. They expressed their confidence that the God of mercy had poured out his Spirit on them according to the promise of the prophet Joel and they were constrained to now offer their bodies and possessions in sacrifice for the holy gospel and spill their blood for this just cause. The following month, the Count pursued two of Cavalier's lieutenants, Abdias Maurel, nicknamed Catinat, and Ravenel, with three companies of mounted troops near Nîmes. The Count was defeated and Captain Poul was killed in battle.

Truce & Betrayal

Skirmishes and punitive expeditions dragged on in the early months of 1703. A promise of amnesty was made in June 1703 for those who laid down their arms and was interpreted by the Camisards as a sign of weakness. Cévenols whose homes had been destroyed swelled the ranks of the Camisards. The combats continued with both resounding victories and stinging defeats for the insurgents. In March, the united troops of Rolland and Cavalier were soundly defeated at Pompignan. New converts to Catholicism from Mialet and Saumane, suspected of aiding and abetting the Camisards, were deported to Perpignan.

There were further attempts to depopulate the Hautes-Cévennes through the methodic destruction of villages, followed by reprisals from Rolland against Catholic villages and Camisard victories led by Cavalier. Finally, Louis XIV sent field marshal de Villars to Languedoc as a replacement for field marshal de Montrevel with assurances of limited freedoms. This new proposal led to defections among the Camisards, and Cavalier himself proposed negotiations. He was seduced by de Villars' offer to form a regiment of Camisards of which he would be colonel, and he also accepted a verbal promise of freedom of conscience. The king had no intention of having a regiment of Camisards among his troops, and Cavalier and one hundred of his men were escorted by the king's soldiers from the province with promises unfulfilled, never to return.

The remaining Camisards considered Cavalier a traitor and banded together with Rolland, who refused to surrender and awaited assistance from his allies. He was betrayed by a young cousin and delivered to Nicolas de Lamoignon de Bâville (l. 1648-1724), who governed Languedoc from 1695 to 1718. Trapped in the château of Castelnau-Valence, Rolland was shot to death on 14 August 1704 while attempting to flee; his cadaver was dragged through the streets of Nîmes, and his five companions were executed. After Rolland's death, the Camisards were demoralized. One by one their leaders surrendered and were allowed to leave the kingdom for Switzerland.

There was one final attempt at revolt in the spring of 1705, but the conspiracy was discovered and the perpetrators severely punished. Several of Cavalier's and Rolland's men were seized and executed at Nîmes. Among them, Henri Castanet (l. 1674-1705), leader of the Mont Aigoual region, was captured and died on the rack before 10,000 spectators at Montpellier. Catinat and Ravenal were captured and executed at Nîmes, dressed in shirts covered with sulfur and burned at the stake. Only Abraham Mazel remained, who after his escape from prison attempted an insurrection in Vivarais. He and 60 peasants resisted for one year against the royal troops before his betrayal and death on 7 October 1710. His companions were hanged or put to death on the rack.