Before Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun's tomb, he began his career as a 17-year-old artist on an excavation in Egypt. His skills were soon recognized, and he quickly rose to be an excavator and later chief inspector for Luxor. Because of a misunderstanding with Gaston Maspero, Director of the Antiquities Service, Carter resigned and became an independent excavator. In need of funding, he teamed up with Lord Carnarvon, and for years the duo searched the Valley of the Kings for the missing tomb of Tutankhamun.

Discovery in Valley of the Kings

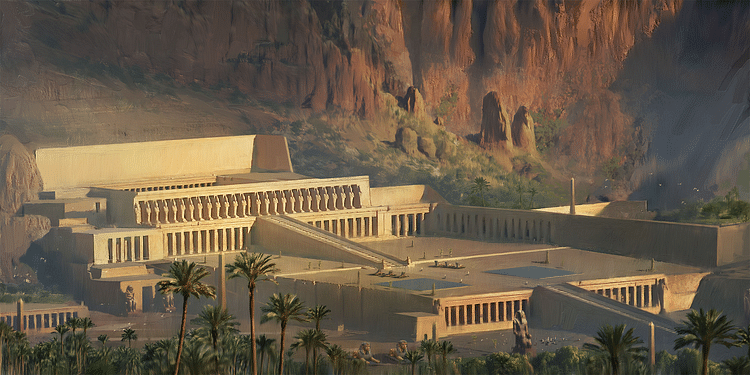

On 1 November 1922, Carter began what he knew might be his last season of excavation. Finally, he was working at the undisturbed triangle of land just below the tomb of Ramesses VI. The first order of business was to clear away the ancient workmen's huts. The workmen who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings had lived in a village on the far side of a very high ridge on the other side of the Valley. It was a long walk from the village, up one side of the ridge and then down the other into the Valley, so sometimes they spent the night in temporary circular stone huts near where they worked. Family members would be sent at various times of the day to bring food to them. The village, today called Deir-el-Medina, was a tightly-controlled community. There was a wall surrounding their houses and only one gate for entering or leaving the community. The members of this community of painters, carvers, and plasterers were often in close proximity to the treasures of the pharaohs, and they were watched very closely.

Because the Valley was never inhabited and until recently rarely visited, the huts these workers slept in were still present, so Carter recorded them for posterity, and then they were dismantled so the team could excavate down to bedrock. After a day of clearing, on 4 November, one of the workmen discovered a step cut into the valley floor. It was a very good sign. Normally steps were cut into the bedrock for about 20 feet (6 m), and then the tomb was hollowed out of the limestone horizontally. The clearing continued, and by the evening of 5 November, they had uncovered twelve steps, revealing the upper part of a doorway with the royal necropolis seal still in place.

Carter knew he had almost certainly discovered a king's tomb, but he could not determine which king. Through a small hole near the top of the doorway, he could see that the passage behind the plastered door was filled with rubble to deter tomb robbers. There was a chance the tomb might be intact. What bothered Carter was the narrow stairway, only about 6 feet (1.8 m) wide; the entrances to other royal tombs were considerably wider. Somehow able to keep his excitement in check, he had the workmen fill in the stairway with sand and rubble and cabled his patron, Lord Carnarvon, who was still in England: "At last have made wonderful discovery in Valley; a magnificent tomb with seals intact, recovered same for your arrival; congratulations."

We know that Carnarvon suspected they had finally found Tutankhamun because when he received Carter's telegram he called Alan Gardiner to ask if he thought it could be Tutankhamun's tomb. Gardiner, always the cautious scholar, told Carnavon that he really could not say; excavating was not his specialty. Carter waited nearly three weeks for Carnarvon, who finally arrived in Alexandria on 20 November 20, accompanied by his daughter, Lady Evelyn. Carter went to Cairo to meet them, and the three took the train to Luxor. We can only imagine the conversation.

Opening the Tomb

When they arrived in Luxor the stairway was cleared again, and this time Tutankhamun's cartouche was revealed on the lower part of the sealed door. When the door was removed, the excavators could see a narrow path through the rubble, almost certainly made by ancient robbers. The tomb had been entered before.

Word of the discovery spread throughout Luxor to the other teams that were excavating, and then throughout the world. Newspapers ran speculative articles about the king inside and what treasures the tomb might contain. At this point, no one really knew, but one French newspaper, Le Pèlerin, ran an imaginative drawing of what the scene would be like when the wall was taken down and Carter and Carnarvon went inside.

23 November was devoted to clearing the 30-foot-long (9 m) descending passage that led to the tomb. Strewn among the limestone chips were alabaster jars, pottery, and workmen's tools. Finally, they reached a second plastered door. There was clear evidence of the door having been breached and then resealed. Carter made an opening in the upper left corner of the doorway to insert a candle for testing the air inside. One can do no better than to let Carter's words describe the scene:

At first I could see nothing, the hot air escaping from the chamber causing the candle flame to flicker, but presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues, and gold – everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment – an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by – I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, "Can you see anything?" it was all I could do to get out the words, "Yes, wonderful things."

The room into which Carter peered was packed with all the possessions Tutankhamun would need in the next world – chariots, statues, game boards, linens, jewelry, beds, chairs, even a throne; they were all piled on top of each other. The ancient robbers had apparently been caught in the act or frightened away, for little had been disturbed. The tomb was virtually intact.

It had been a long day, and the tension of not knowing what they would find had exhausted everyone. The tomb was closed, guards were posted, and the small team left. On the 27th, they returned to remove the wall they had breathlessly peered through. Electric lighting was brought into the tomb, and for the first time, they could see the magnitude of what they had discovered. The room they had first looked into by candlelight was about 26 by 13 feet (8x4 m) and packed with objects the likes of which no one had ever seen before. There was a set of three waist-high funerary couches made of gilded wood decorated with the heads of animals, which had been used for rituals performed on the mummy of Tutankhamun. Against the north wall were two life-sized guardian statues protecting something behind the wall, almost certainly the Burial Chamber. The room they had entered was merely the tomb's Antechamber.

Now that they were inside the room, with good lighting, Carter and Carnarvon could see a smaller room carved through the west wall of the Antechamber that was about 14 by 9 feet (4.2 x 2.7 m) in floor area and 8 feet (2.4 m) high; this would become known as the Annex. It too was packed with treasures. It would take Carter ten years to clear all the treasures in Tutankhamun's tomb – the famous gold mask, the mummy of the boy-king in its solid gold coffin, statues, jewelry, even the king's sandals. Today, the tomb is still considered by most experts to be the greatest archaeological find of all times.