The island of Sri Lanka (formerly known as Ceylon) became a focus of European attention soon after the Portuguese entry into the Indian Ocean in the late 15th century. Large swaths of the island would come first under Portuguese control, then Dutch and English. Sri Lanka would be under European control for almost four and a half centuries until it received its independence from Great Britain in 1948.

Sri Lanka before the European Conquest

When the Portuguese began their conquest of the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka was an important stopover for Indian, Arab, and Chinese merchants, where the world's finest cinnamon could be obtained, along with gems, pearls, ivory, elephants, turtle shells, and cloth. Ships from across the Eastern world came to Sri Lanka for its native products and goods brought to it from other countries.

Sri Lanka held a key strategic position in the Indian Ocean between the East and West, being located next to India and along the sea routes that connected the Middle East with East Asia and China. There were numerous bays and anchorages dotting the coast of the island, which provided calm harbors and facilities for ships. At the end of the 15th century, the most important port was Colombo, well populated with Muslims who had settled there to carry on trade. Tomé Pires, the Portuguese chronicler of Indian Ocean trade in the 15th century, described the island:

The beautiful island of Ceylon … is large; it must be three hundred leagues in circumference, much longer than it is wide. It is very populous; it has many towns and large houses of prayer, with copper pillars, and with roofs covered with lead and copper … It has all kinds of precious stones, except diamonds, emeralds, turquoises … It has a great abundance of elephants and ivory; it has cinnamon … Ceylon trades elephants, cinnamon, ivory and areca [palm nuts] with the whole of the Choromandel and Bengal, [and] Pulicat, taking rice, white sandalwood, seedpearls, cloth and other merchandise in return. Rice, silver, copper, a little quicksilver, rosewater, white sandal-dise of wood and Cambay cloths.

(Cortesão, 1944, p. 86).

Portuguese Discovery & Conquest

The first European to visit Ceylon was Lourenço de Almeida (c. 1480-1508), son of the first viceroy of India, Francesco de Almeida. He bumped into Sri Lanka on his way to the Maldives from Malacca seeking Arab ships to plunder and destroy. Lourenço made the most of his accidental landing and took on a load of pepper. Surprisingly he did not take on much cinnamon, probably because the bales of cinnamon had to be handled and stowed carefully, while pepper could simply be poured into every available space of the ship.

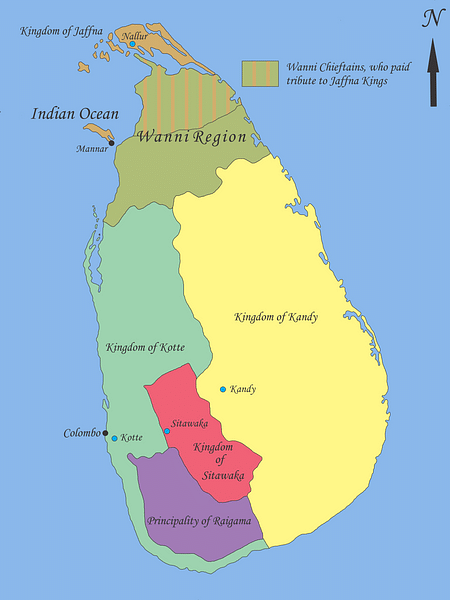

When Almeida blew into Sri Lanka in 1505, there were three kingdoms there, Kotte in the southwest ruled by Vijayabahu VI (1445-1521), Kandy in the west ruled by Sēnasammata Vikramabāhu (1469-1511), and Jaffna in the northeast ruled by Jayabahu II (1469-1511). Trade was dominated by a collection of Arab, Indian, Malay, and Chinese merchants, who transported a wide spectrum of cargo, from spices to elephants. The Portuguese first contact was with Kotte, whose king gave them favorable trade concessions in 1518 and allowed them to build a fort in his capital at Colombo.

In 1521, the three sons of the King of Kotte had him assassinated, then partitioned the kingdom among themselves and commenced fighting. The eldest, Bhuvanaikabahu VII (r. 1521-1551), took control of the northwestern half of Kotte; another, Pararajasinghe (r. 1521), became the ruler of Raigama in the southern quarter of the old kingdom; and the third, Mayadunne (r. 1521-1581), became king of Sitawaka in the east. Bhuvanaikabahu reached out to the Portuguese to help maintain and build his kingdom, while Mayadunne allied himself with the powerful Muslim zamorin of Calicut, India. He became a fierce opponent of the Portuguese and dedicated his life to overthrowing Bhuvanaikabahu, to preserve the independence of Ceylon. The other brother, Pararajasinghe, kept Raigama neutral.

Over time, Bhuvanaikabahu became more and more dependent on the Portuguese for his defense, and in 1556, his heir, Dharmapala, was converted from Buddhism to Christianity by the Franciscan order of the Roman Catholic Church. When his conversion was announced, there was a great public outcry, and as a result, he was forced to rely even more on Portuguese protection. In 1580, the Portuguese convinced him to deed his kingdom to them, and after his death, they took formal possession of it.

Mayadunne and his successor son Rajasinha were able to hold the Portuguese at bay on land for most of the 16th century but were almost defenseless against Portuguese sea power. When Rajasinha died without a clear successor in 1593, his kingdom disintegrated and was absorbed by the Portuguese.

Mostly Hindu, Jaffna fought mightily against Catholic conversion, and through most of the 16th century, the influence of the Portuguese remained minimal. However, in 1591 under the instigation of Christian missionaries, the Portuguese invaded and installed a puppet government in Jaffna. In 1619, the Portuguese undertook another expedition and fully annexed the kingdom.

As the 16th century ended, the Portuguese controlled most of the island, except the Central Highlands and the eastern coast of the Kingdom of Kandy, where Vimaladharmasurya I (r. 1590-1604) now had control. The Portuguese were eager to establish hegemony across the entire island and fought long and hard against him. They suffered two humiliating defeats in the Battle of Danture in 1594 and the Battle of Balana in 1602, but ultimately, they were able to expand their control to the lower reaches of the Central Highlands and the east coast ports of Trincomalee and Batticaloa.

Portuguese Ceylon

Under Portuguese control, the administrative structure of the Kotte kingdom was retained, with the Portuguese taking the highest offices, while local offices were given to members of the Sinhalese nobility loyal to the Portuguese. The long enduring system of service tenure was maintained and was used to secure the traditional products of the land for trade, such as cinnamon, gems and elephants. The long-held caste system was kept intact, and all obligations that had been due to the king were transferred to the Portuguese state. The period of Portuguese influence was marked by intense Roman Catholic missionary activity including first Franciscans and Jesuits, and then Dominicans and Augustinians. Overall, the Portuguese largely ignored the traditional social structure of the Sinhalese, which led to widespread hardship and popular hostility.

Dutch Takeover

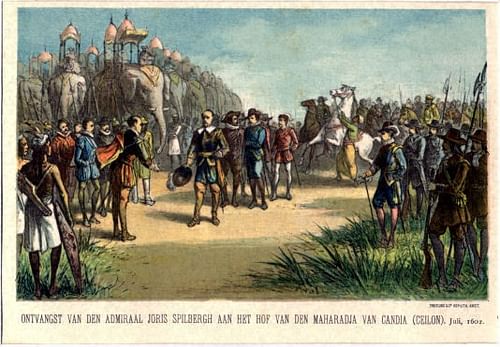

In 1602, Admiral Joris van Spilbergen was the first Dutch envoy to make contact with the rulers of Ceylon at Kandy. Spilbergen and King Vimaladharmasuriya I hit it off, and they developed quite cordial relations. The king saw the Dutch arrival as an excellent opportunity to gain naval support against his Portuguese adversaries, and Spilbergen made lavish promises about military assistance. The king was so impressed by his visitors that he began to learn Dutch, and Spilbergen left a couple of musicians behind to entertain the king.

A few months later another Dutch official, Sebald de Weert, arrived with a fleet of six ships and a concrete offer of help. The king agreed, and they launched a joint attack on the Portuguese at Batticaloa on the eastern coast. During the attack, Weert took four Portuguese ships but allowed the officers and crews to go free. The king was furious about this action, and after Weert insulted the queen at a drunken dinner party, he and all 47 Dutchmen with him were slaughtered. This tragedy spooked the Dutch, and it was another three decades before they made another serious attempt to work with the locals to expel the Portuguese from Sri Lanka.

The Dutch returned in force in 1637, after the new King Rajasinha II (r. 1629-1687) sent emissaries to meet the admiral of the Dutch fleet, Adam Westerwolt, who was then blockading Goa, India. After decimating the Portuguese fleet there, the victorious Westerwolt took four ships and 800 men and attacked the Portuguese fort at Batticaloa, aided by Singhalese forces. The coalition conquered the fort on 18 May 1638, and five days later, Westerwolt signed a new treaty with King Rajasinha, the Kandyan Treaty of 1638. Under the treaty, the Dutch would make war with the Portuguese and in return would be given a monopoly over all trade except elephants, and any forts captured from the Portuguese would be garrisoned by the Dutch at the king's expense.

Slowly but surely the Dutch and Kandyan forces pushed the Portuguese out of Sri Lanka. In May 1639, the Dutch fleet captured Trincomalee, and in February 1640, the Dutch and the Kandyans combined to take Negombo. In March 1640 Galle was also taken, but the Dutch invasion was temporarily halted by a truce declared in Europe between the Dutch Republic and Spain. In 1645, the boundaries between the two countries' territories in Ceylon were demarcated, and Jan Thijssen was appointed the first governor of the Dutch zones.

The Dutch resumed their open warfare against the Portuguese in 1656 and sent Gerard Pietersz Hulft (1621-1656) to Sri Lanka with eleven ships and 1120 soldiers. The Dutch took the Fort of Kalutara outside of Colombo and then laid siege to the city. The Portuguese surrendered on 12 May 1656, ending 150 years of their presence in the city. In 1658, the Dutch advanced north and captured Jaffna and Mannar, the last Portuguese strongholds on the island. In supporting the Dutch, King Rajasinha II wound up where he started – replacing one occupier with another. He had been duped by the Dutch into thinking he would have more control when the Portuguese were defeated.

Dutch Ceylon

A Dutch governor, residing in Colombo, became the chief executive, assisted by a council of high officials. The country was divided into three administrative divisions – Colombo, Galle, and Jaffe. Colombo was ruled by the governor, and the other two by Dutch commanders. To facilitate trade, the VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie – Dutch East India Company) developed three major canal systems in the western, southern, and eastern parts of the country. Cinnamon and betel were initially the most important items in the export trade, followed by gemstones from Central Highlands mines and pearls from the sea. Other important exports included the other southeastern spices, lacquer, coconut oil, ropes of coconut fiber, and conch shells. Elephants were an important export to India. By the middle of the 18th century, two additional export crops were widely planted: tobacco in the Jaffna peninsula and coffee across the island.

British Takeover

In 1793, Great Britain and the Dutch Republic went to war with the French Republic. Despite the best efforts of the Dutch army and a British expeditionary force, the Dutch were defeated by the French in the winter of 1794-1795, and the French reconstructed the country into a client state, the Batavian Republic. In response, the British government began seizing all Batavian shipping to prevent the French from profiting from it, and on February 9, war was formally declared between Britain and the Batavian Republic. Lord Hobart (1760-1816), Governor of Madras in India, was ordered by the British government to invade the former Dutch-, now Batavian-held ports of Ceylon. Colonel James Stuart was given command of the army which would be supported by naval forces under Rear-Admiral Peter Rainier (1741-1808).

Stuart began the invasion by calling on the Batavian governor Johan van Angelbeek (1727-1799) and asking him to surrender the colony peacefully. He carried letters of support from the Dutch leader in exile, William V of Orange (1748-1806), directing cooperation with British forces. Van Angelbeek complied and allowed 300 British troops to land at Fort Oostenberg, which overlooked Trincomalee. However, the commander of the defenses there refused to accept the handover, forcing the British to attack. The British forces emplaced eight 18-pounder long guns and a number of smaller cannons and began a bombardment of Trincomalee. After two days, the Batavian commander surrendered. The entire garrison of 679 troops was taken prisoner, and more than 100 cannons were seized by the British. British losses totaled 16 killed and 60 wounded. With resistance broken, the series of Batavian trading posts along the Ceylon coastline surrendered in quick succession, including Batticaloa on 18 September, Jaffna on 27 September, Mullaitivu on 1 October, and the island of Mannar on 5 October.

In September, Rainier assigned Alan Gardner to blockade Colombo, the last Batavian-held territory on the island. A final expedition was unleashed in January, with Stuart again at the command, supported by Gardner in Heroine and the sloops HMS Rattlesnake, Echo, and Swift, as well as five additional British East India ships. Stuart's force disembarked at Negombo, where a Dutch fort was already abandoned, and marched overland to Colombo, arriving without opposition on 14 February. The garrison was told to surrender or face a bloody assault, and on 15 February, van Angelbeek agreed to capitulate. Colombo would remain a part of the British Empire for the next 153 years.

After the defeat of the Dutch, Great Britain had possession of the coast of Ceylon, but the center of the country was still controlled by the Kingdom of Kandy. In 1796, the British asked the king of Kandy to allow them to replace the Dutch as protectors of his kingdom. However, the British soon realized that Kandy's independence would still pose problems for them. The frontier would have to be guarded at much expense, and trade with the highlands would be greatly hampered by custom regulations and political insecurity. Also, communication between the east and west coasts would be greatly facilitated if the British were able to build their own roads through the center.

The first British attempt to capture the kingdom outright came in 1803 and ended in failure, as the king was popular, and the nobility united behind him to rout the British forces. However, a new window of opportunity opened when growing dissensions within the kingdom grew over time. Using the support of local Kandyan chiefs who had become unhappy with the king, the British forces succeeded in taking over the kingdom in 1815.

British Ceylon

In 1802, Ceylon was made a crown colony of the British, and in the Treaty of Amiens with France, their permanent possession of Ceylon was established. While the British monarch was considered the head of state, in practice the colony was run by a colonial Governor, who acted on instructions from the British government in London. Under the British, restrictions on European ownership of land were lifted, and Christian missionary activity became intense. Agriculture was greatly encouraged, and the production of cinnamon, pepper, sugarcane, cotton, and coffee flourished.

In the mid-19th century, coffee rose to the center of Ceylon's economic development, and the British made way for new coffee plantations by removing what was an almost impenetrable rainforest in the Kandyan Highlands. They continued this assault through the 1880s until all the highlands of central Ceylon were completely denuded and planted with coffee. In the 1870s, the coffee plantations were destroyed by a leaf disease, and they were replanted with tea, as well as rubber and coconut. So many laborers were needed on the plantations that indentured workers were brought in from southern India in huge numbers.

Independence of Sri Lanka

The British would rule Ceylon until 1948 when the country was granted its independence. The movement towards independence was a long and tortuous process that began at the turn of the 19th century, pushed by the nationalism of a rising British-educated middle class and communal unhappiness about representation. The country's constitution went through several slow and painful revisions that gradually increased the elected representation of different segments of Sri Lankan society and decreased the power of a British executive. In 1947, the Ceylon Independence Act conferred dominion status on the colony, whereby Ceylon was recognized as an autonomous entity with allegiance to the British Crown. In 1972, the country became a republic within the Commonwealth, and its name was changed to Sri Lanka.

![The Jeweled Isle: Art from Sri Lanka Exhibition, LACMA [1]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/c/p/360x202/9765.jpg?v=1599127202)

![The Jeweled Isle: Art from Sri Lanka Exhibition, LACMA [3]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/c/p/360x202/9767.jpg?v=1599127203)