The Proslogion (Latin for Address or Discourse; the title was chosen because it is written in the form of a prayer addressed to God) is a book written by the medieval theologian St. Anselm of Canterbury (c. 1033-1109). It is of great significance in the history of philosophy, mainly because of the proof of God's existence that Anselm gives in Chapters Two and Three of the work.

Anselm's Life

Anselm was born in 1033 or 1034 at Aosta in what is now north-western Italy. A religious man even from his youth, he left home at the age of 23 to travel through France and Burgundy, before joining the abbey of Bec in Normandy at the age of 27. Three years later, he was elected abbot of the monastery, a remarkable honour for one so young. Under Anselm's direction, Bec became famous as a centre of learning, attracting students from as far away as Italy. Anselm was also notable for the pains he took to keep the abbey independent of outside control, both secular and ecclesiastical.

Following the Norman conquest of England, Bec had been granted extensive lands in that country, and Anselm visited England several times to oversee the monastery's property. He evidently made a good impression during these visits, as after the death of Archbishop Lanfranc of Canterbury in 1089, the cathedral chapter wanted to appoint Anselm as his successor. (Coincidentally, Lanfranc had also preceded Anselm as abbot of Bec.) Anselm was not formally invested until 1093, partly due to his own unwillingness to leave his monastery, and partly because William II of England (r. 1087-1100) wished to keep the cathedral's revenues for himself.

Much as he had done as abbot of Bec, Anselm showed great concern to maintain his new see's independence. This led him into conflict with England's monarchs, who wished to exert greater control over ecclesiastical affairs, and he was twice forced into exile, the first time in 1097 and the second time in 1105. The conflict died down somewhat after the Concordat of London of 1107, which recognised the English Church's authority to appoint its own bishops without royal interference. Anselm died in 1109 and was buried in Canterbury. He was venerated as a saint soon after his death, and in 1720, he was granted the title Doctor Ecclesiae, or Doctor of the Church.

Writing the Proslogion

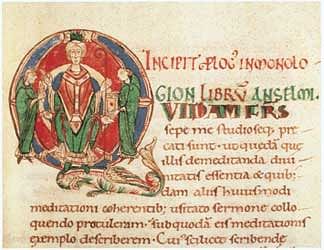

Anselm began writing soon after joining the monastery at Bec. His most important early work was the Monologion (Latin for Monologue), published in 1076, in which he argued that Christian beliefs about God can be proved by philosophical reasoning alone, without relying on biblical authority.

Despite the Monologion's success, however, Anselm was not satisfied. He had used a wide variety of arguments in the Monologion, but he now began to wonder whether it might not be possible to find "a single argument, which would require nothing else to prove it but itself alone, and which on its own would suffice to show that God really exists … and whatever else we believe about the divine nature" (Anselm, Proslogion, Preface). Anselm's attempts to find such an argument were unsuccessful at first, but the more he tried to forget the issue, the more it pressed upon his mind, so much so that he began to wonder whether the whole thing was not merely a temptation sent by the Devil. At last, however, according to his biographer Eadmer, he found what he was searching for in a flash of divine inspiration: during morning prayer, "the argument he had sought displayed itself clear and bright to his mental vision, and his inmost soul was deluged with unspeakable joy and gladness" (Eadmer, Life of St. Anselm, 196).

Anselm composed the Proslogion soon afterwards to showcase his new argument. The text is written in the form of a prayer by a man seeking to understand God better: "And come now, O Lord my God, teach my heart where and how it may seek you, and how it may find you" (Chapter 1). Its original title was Fides Quaerens Intellectum, or Faith Seeking Understanding, but it was later renamed the Proslogion at the suggestion of Anselm's friend, Archbishop Hugo of Lyons.

Anselm's Argument for the Existence of God

The most influential and widely-read section of the Proslogion is the argument for the existence of God, which Anselm gives in Chapters 2 and 3. It is usually considered the first ever ontological argument, that is, the first argument that seeks to prove God's existence based on reason alone rather than on observation of the world around us. It can be summarised like this:

- God is defined as that than which nothing greater can be thought.

- Even a fool, who denies the existence of God, understands the phrase "that than which nothing greater can be thought".

- Whatever is understood exists in the intellect.

- Therefore, that than which nothing greater can be thought exists in the intellect.

- To exist in reality is greater than to exist in the intellect.

- If that than which nothing greater can be thought existed in the intellect but not in reality, it would be possible to think of something greater, namely an equivalent being which also exists in reality. But this is clearly absurd.

- Therefore, that than which nothing greater can be thought exists in reality as well as in the intellect.

Anselm then spends the rest of the Proslogion proving that that than which nothing greater can be thought would have to have the attributes traditionally ascribed to God, including omnipotence, omniscience, and omnipresence.

The Proslogion's Reception

Almost as soon as it was published, the Proslogion was criticised by another monk, Gaunilo of Marmoutiers. Gaunilo claimed that Anselm's argument proves too much since we can apply the same reasoning to "prove" the existence of all manner of things – Gaunilo uses the example of an island which is better than any other island. Anselm countered that Gaunilo had missed the point and that since it is possible to think of something better than even the best possible island, the logic used in his Proslogion does not apply to Gaunilo's island. He asked that future editions of his book include copies of Gaunilo's response On Behalf of the Fool and Anselm's own counter-argument as well as the original Proslogion.

In the 13th century, the famous theologian Saint Bonaventure presented an adapted version of Anselm's ontological argument in his Disputed Questions on the Mystery of the Trinity (Question 1, Article 1, Sections 21-4). Bonaventure's contemporary, St. Thomas Aquinas, was unconvinced by the proof, however. He argued that (leaving aside divine revelation) we can only know about God indirectly, by drawing inferences from the created world (Summa Theologiae, 1.2.1). Thanks to Aquinas' reputation among later theologians, Anselm's ontological argument fell into obscurity, although Anselm himself continued to be held in high esteem and was venerated as a saint. The 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes gave a very similar argument in his fifth Meditation, although he claimed not to have read Anselm and to have developed his own version of the proof independently. Later philosophers generally associated the ontological argument with Descartes or with Leibniz, who had come up with an improved version of Descartes' argument rather than with Anselm.

The 20th century, however, saw a resurgence of interest in the Proslogion and in Anselm's ontological argument. Traditionally scholars focused their attention on Chapter 2 of the Proslogion, although some argued that Anselm's ontological argument extends into Chapter 3 as well, and others claimed that Anselm actually presents two separate arguments: one in Chapter 2 and the other in Chapter 3.

Extract from the Text

CHAPTER 2. Therefore, O Lord, who give understanding to faith, grant that I may understand, as much as you know is expedient, that you are as we believe and that you are what we believe. And indeed we believe you to be something than which nothing greater can be thought. Or is there perhaps no such nature, since The fool hath said in his heart, There is no God (Psalm 13.1, 52.1)? But certainly that very same fool, when he hears me say "something than which nothing greater can be thought", understands what he hears; and what he understands is in his intellect, even if he does not understand that it exists. For it is one thing for something to be in the intellect, and another to understand that that something exists. For when a painter thinks of what he is going to paint, he assuredly has it in his intellect, but he does not yet understand that it exists, because he has not yet painted it. But, when he has painted it, he both has it in his intellect and understands that it exists, because he has already painted it. Hence even the fool is bound to concede that that than which nothing greater can be thought at least exists in the intellect, because when he hears this he understands it, and whatever is understood exists in the intellect. And certainly that than which a greater cannot be thought cannot exist in the intellect alone. For if it exists only in the intellect, it can be thought to exist in reality as well, which is greater. If, therefore, that than which a greater cannot be thought exists only in the intellect, that very thing than which a greater cannot be thought is something than which a greater can be thought. But this is assuredly impossible. Therefore something than which no greater can be thought undoubtedly exists, both in the intellect and in reality.

CHAPTER 3. And assuredly it exists so truly that it cannot even be thought not to exist. For it can be thought to be something which cannot be thought not to exist, which is greater than that which can be thought not to exist. Therefore, if that than which a greater cannot be thought can be thought not to exist, that same thing than which a greater cannot be thought is not that than which a greater cannot be thought, which is impossible. So truly, therefore, is there something than which a greater cannot be thought, that it cannot even be thought not to exist. And this is you, O Lord our God. For you so truly exist, O Lord my God, that you cannot even be thought not to exist. And rightly: for if some mind could think of anything better than you, then the creature would climb above its Creator and sit in judgement over him, which is utterly absurd. And indeed anything apart from you alone can be thought not to exist. You alone, therefore, have existence most truly, and therefore most greatly, of all things; for whatever else exists does not exist so truly, and therefore has less existence. Why, then, has The fool said in his heart, There is no God, when it is so obvious to the rational mind that you exist most greatly of all things? Why indeed, except because he is stupid and a fool?

Conclusion

The Proslogion remains controversial today, not least because few of its defenders can agree on what Anselm was trying to say, and few of its critics can agree on where he goes wrong. Nevertheless, it is widely agreed that Anselm raises important questions on the nature of thought and existence, and his ontological argument looks set to retain its status as "the only general, non-technical philosophical argument discovered in the Middle Ages which has survived to excite the interest of philosophers who have no other interest in the period" (Southern, 128).