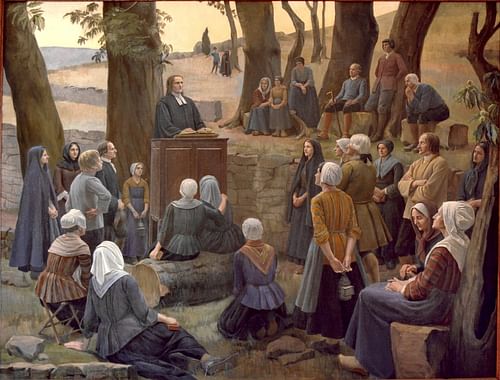

In March 1715, Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) issued a declaration stating that all subjects of the king were also subjects of the Catholic Church. In defiance of the king's decree, Antoine Court (l. 1696-1760) gathered a small group of believers to lay new foundations for Reformed churches in France. Protestant believers continued to meet clandestinely in what was known as the 'Church of the Desert'.

Christian France Divided

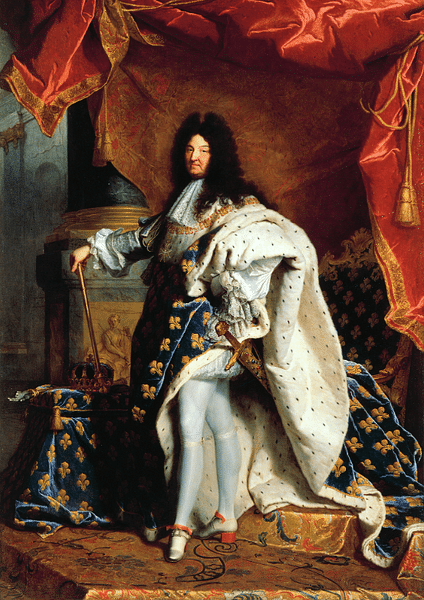

Through the influence of the teachings of Reformation leaders Martin Luther (l. 1483-1546) and John Calvin (l. 1509-1564), Protestants in the 16th century separated from the Catholic Church and sought freedom of conscience and religion. The introduction of the Protestant Reformation in France led to the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598) between Catholics and Protestants. The nation was devastated for over 30 years through war, famine, and disease. Treaties brought brief periods of peace but did not stop the bloodshed. The wars ended in 1598 with Henry IV of France and the Edict of Nantes. Henry IV of France (r. 1598-1610) converted to Catholicism and issued the Edict of Nantes by which Protestants were granted limited religious rights. After Henry IV's assassination in 1610, these religious rights were eroded under Louis XIII of France (r. 1610-1643) and then repealed in 1685 by Louis XIV and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. Protestantism was outlawed.

Church of the Desert

Following the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes, an estimated three-fourths of Protestants renounced their faith. Those who remained in the regions of southern France worshipped illegally, some in homes, others in secret places. This period became known as the Church of the Desert. By 1700, most pastors were either dead or in exile. In the absence of pastors, self-appointed prophets and prophetesses multiplied who called for armed resistance. In defense of their homes and religious liberty, peasant warriors launched the War of the Camisards in the Cévennes (1702-1705) to reclaim their lost religious rights.

The early success of the Camisards was partly due to their knowledge of the rugged terrain of the region. They were emboldened by early victories, yet in the end, they were no match for heavily armed royal forces. One by one their leaders surrendered or were killed. Survivors were allowed to leave the kingdom for countries of refuge. In abandoning violence, the Church of the Desert entered a new phase in 1715 under the leadership of Antoine Court. The years 1715 to 1760 became known as the 'heroic period' of the Church of the Desert when Protestant gatherings were forbidden and those arrested were severely punished.

Antoine Court's Early Years

Antoine Court came on the scene after the War of the Camisards. From humble beginnings, he became known for remarkable exploits of faith during a long and sorrowful period in French history. Court was born in Villeneuve-de-Berg in Vivarais and was baptized in the Catholic faith as required by law. He accompanied his mother to the illegal assemblies of the Church of the Desert where prophetesses had replaced exiled pastors. Following the non-realization of prophecies, he broke with the movement of prophetism, rejected violence previously associated with the Camisards, and fought to reverse the consequences of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. On 21 August 1715, only ten days before the death of Louis XIV, the most powerful monarch of Europe, Court organized the first synod of the Church of the Desert at Montèze to replant the church which Louis XIV had sought to abolish.

Louis XIV's death sparked great hope among the Huguenots, both in the kingdom and in exile, for the re-establishment of the Edict of Nantes. Their hope did not long survive. After the arrest of a young preacher, Étienne Arnaud, Court opposed a project to liberate Arnaud who was put to death by hanging at Alès on 22 January 1718 in the presence of a large crowd. His death had a great impact on Protestants beyond the Cévennes region; he became a martyr. Two years later, in the region of Nîmes, another assembly was called with Court and other leaders of the Church of the Desert. The king's troops intervened, and Court escaped, but 50 others were arrested. As an example to others, 20 men were initially sentenced to the king's galleys for life. The sentence was commuted to deportation to Louisiana. They were transported through France to La Rochelle where they were freed by Protestant powers and exiled to England.

Louis XV

Louis XV of France (r. 1715-1774) reaffirmed the Edict of Revocation in 1724 with a single text declaring France a Catholic nation. Protestants who had converted to Catholicism and then returned to Protestantism were considered 'relapsed' and were subject to harsh penalties. Although the royal decree was applied sporadically and never consistently throughout the kingdom, there was great consternation among Protestants. Submission was unthinkable, further emigration might announce the end of French Protestantism, and armed revolt would annul the decision ten years earlier when Protestants had chosen a strategy of non-violence. Their response had two parts. On one hand, they planned to organize peaceful public gatherings to demonstrate to the authorities that French Protestants still existed in the kingdom. The assemblies would disperse at the announcement of the arrival of troops. On the other hand, they would refuse to participate in Catholic ceremonies, particularly baptism, marriage, and extreme unction. It fell to Antoine Court at a synod in 1725 to convince Protestants of the wisdom of these actions. He reminded his listeners of Louis XIV's attempt to destroy Protestantism and how through the years God had raised up leaders to sustain his people.

Court's Writings

In his works, Court addressed what he believed was the greatest problem in reorganizing Reformed churches – the War of the Camisards. He emphasized a distinction between the present assemblies of the Church of the Desert organized by pastors and the assemblies in the past characterized by violence and prophecies. Although never a Camisard himself, he admitted that at the age of 18 he came under the influence of prophetesses. At that time he wrote letters to priests in which he threatened a new uprising if persecution continued. In his rejection of self-proclaimed prophets and prophetesses, his goal was the return of churches to the pre-Revocation pastoral model of leadership, refrain from violence, and submit to political authority. This change of strategy had the intention of winning the battle of public opinion in France and among those in exile. Although he separated from those who claimed prophetic inspiration, he remained surrounded by many who had participated in the War of the Camisards. For those who had experienced systematic persecution, conversion to non-violent resistance was difficult to accept.

In his book, Histoire des troubles des Cévennes, Court showed how intolerance and the dearth of spiritual leadership contributed to the impossibility of controlling processes that led to violence instigated by the prophetic utterances of Camisard leaders. He insisted that the situation following the rebellion influenced his strategy of non-violence, which was more consistent with evangelical principles. Yet others claimed that Court was unable to admit that the threat of insurrection often stopped the authorities from exercising harsh repression. To his opponents, Court remained a prisoner of a mindset that accorded undeserved reverence to the monarchy.

In 1729, Court left France permanently to find refuge at Lausanne. There he founded a seminary and through his writing continued defending Protestants from accusations of treason against the monarchy. In his later writings, he sought to reconcile the early Camisard period of violence with the non-violent reorganized Church of the Desert under his leadership. It seems, however, that he could not admit that the insurrection of the Camisards facilitated the passage to non-violence and that the fear of a new uprising held the authorities in check. His 118 volumes of testimonies and letters from galley slaves and exiles constitute the greatest and most varied source of the history of the Church of the Desert.

Antoine Court found himself confronted by questions that go beyond his time and resonate in the 21st century. Is there a clear boundary between violence and non-violence? In extreme situations, how do we articulate and differentiate between legality and legitimacy? What sustains people in times of persecution? Even if Court did not always have the right response, he asked the right questions. Although he adopted a strategy of non-violence and submission to political authority, his objective remained the same as the Camisards' – obtain the freedom of conscience, the freedom to be born, to live, and to die outside a state religion. His writings and position on relations between religion and state and the fear of a new Camisard uprising undoubtedly contributed to the religious tolerance that eventually gained ground in Languedoc and throughout France.