The East India Company (EIC) was first England's and then Britain's tool of colonial expansion in India and beyond. Revenue from trade and land taxes from territories it controlled allowed the EIC to build up its own private armies, collectively the largest armed force in South and South East Asia.

The EIC mixed British and Indian soldiers (sepoys), hired regular regiments of the British Army, and funded its own navy, the Bombay Marine. The vast resources of the company allowed it to eventually employ over 250,000 well-trained and well-equipped fighting men. This force expanded the EIC's domains, seeing off competition from Indian princely states, pirates, and other European trade companies.

From Trade to Imperialism

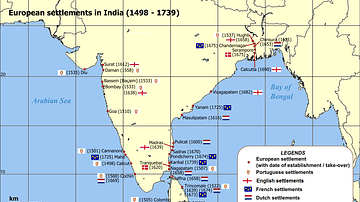

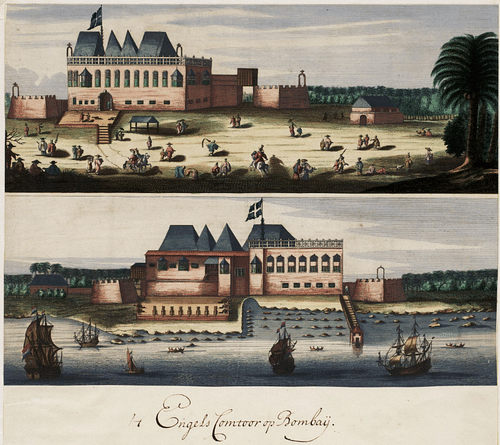

The East India Company was founded as a joint stock company by royal charter on 31 December 1600. Initially, the company limited itself to trade from centres or 'factories' it set up at already established ports belonging to the Mughal Empire (1526-1858) in India. From 1668, Bombay (Mumbai) became the EIC's main trade hub after it was acquired from the Portuguese Empire. By the end of the century, the EIC had a major presence at Madras, Calcutta (Kolkata), and Hughli in Bengal amongst others. These early arrangements were entirely peaceful, but the EIC wanted more control and more power that would give even greater returns to its private investors.

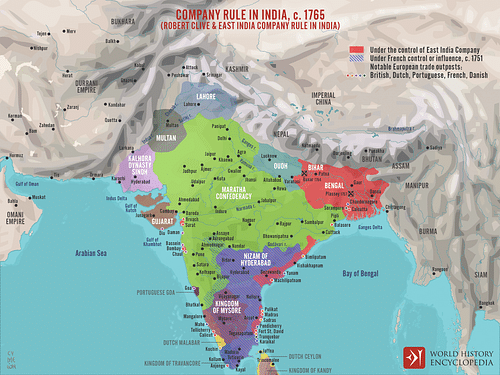

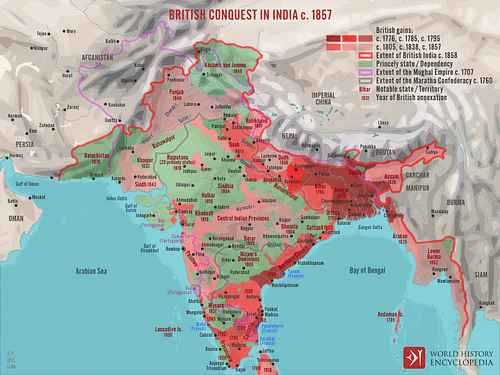

It was in the mid-18th century that the EIC gained the right through a royal charter to raise its own army, principally in order to protect its assets like warehouses and man its fortifications. From 1757, the EIC used this army in an aggressive campaign of conquest. The EIC thus began to control territory of its own, and in 1759, it took over the major port of Surat completely. Essentially, the EIC was now the "sharp end of the British imperial stick" (Faught, 6). A key step in this transformation from trader to imperialist was victory against Shah Alam II, the Mughal emperor, and Mir Qasim, Nawab of Awadh at the Battle of Buxar in 1764. In a 1765 peace treaty, Shah Alam II awarded the EIC the right to collect land revenue (dewani) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. This was a major development and ensured the company now had vast resources to fund an army for further territorial expansion.

Men like Robert Clive (1725-1774) carved out an empire in the EIC's name. Clive of India, as he was popularly known, rose from clerk to Governor of Bengal and secured a famous victory in June 1757 at the Battle of Plassey against the forces of the Nawab of Bengal. Clive defeated a larger enemy force where the wealth of the EIC was seen in the disparity of artillery pieces: 50 against the EIC's 171. More territory came after the Four Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-99) and the two Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-49). These territories had to be protected against various Indian princely states, the Mughal Empire, the Marathas, the Mysores, and rivals such as the Dutch East India Company (VOC), founded in 1602, and the French East India Company, founded in 1664. These European bodies had armies as well-equipped as the EIC forces, and so the British expansion was not entirely a smooth one. For example, the French twice took possession of Madras and controlled large parts of southern India. It is no surprise then, given these challenges, that by the end of the 18th century, the EIC was spending half its income on military personnel and hardware.

The EIC Navy

As the EIC began as an exclusively trading body, its first concern was to protect the valuable goods it shipped across the oceans. An EIC vessel was known as an East Indiaman and these typically carried a formidable 30-36 cannons, far outgunning any pirate vessel and matching some of the warships in European navies. Fortunately for the EIC, the Royal Navy was able to control much of the Indian Ocean, but the EIC still maintained a small navy of its own, known as the Bombay Marine since it was based at that port. EIC ports were also protected by company-built fortresses.

Ships were constructed at company dockyards in Deptford and Blackwall in England or Bombay, but after 1639, the EIC usually hired ships. Well-protected and well-built, the EIC fleet suffered remarkably few losses of its East Indiamen, around 5%. Such was the confidence that ships would safely deposit their cargoes at their appointed destinations, from 1650, the company ceased to insure its ships. Company pay was not generous, but officers were permitted limited space on board to transport goods for personal trade at their destination port.

The EIC Army: Recruitment & Structure

The EIC did not have a single army but rather allowed each of its presidencies (administrative regions) to raise its own force. This was because each trade centre was geographically isolated from the others. Examples of presidencies are Bombay, Madras, and Bengal, each governed by a president (later to be called a governor). As each army was recruited and maintained in isolation, distinctive military traditions developed. The EIC also paid for the garrisoning of regular British Army regiments in India. These regiments were given 20-year tours, and so the company could rely on them long-term to fight alongside its own forces. The two together, EIC Army and British Army, were often collectively called the 'Army in India'.

Another example of company outsourcing was cavalry. The EIC did not have cavalry of its own until the 19th century, preferring instead to hire horses and riders from its Indian allies. These were usually light cavalry, but there were sporadically-formed mercenary units of heavy cavalry known as 'Mogul Horse' where the riders wore metal armour and wielded a lance. The company did have its own specialised artillery units, initially as a defensive force for port fortifications but also later as a mobile unit employed in field engagements. There were, too, small companies of engineers compiled exclusively of officers who were supported by native labourers (variously known as Sappers and Miners, Lascars, or Pioneers). Besides regular troops, the EIC armies relied on a vast number of Indian irregulars, who acted as water carriers, baggage porters, cooks, and transporters of ammunition and cannonballs.

Soldiers were recruited locally, with Indians initially known as peons and then sepoys (from a corruption of the Persian term sipahi). Sepoys far outnumbered European soldiers. The average ratio of Indian troops to British in EIC armies was around 7:1. There were also European mercenaries (particularly Dutch, French, German, and Swiss), Eurasians, and those of Eurasian descent. While Europeans formed specific regiments (which were usually understrength), there was no segregation of non-Europeans based on race or religion. Any nationality could be considered for officer rank until 1765 when it was decided to exclude Indians.

A peculiarity of the EIC armies was the lack of a deep command structure, or rather a severely limited one. Compared to other European armies of the period, the EIC forces contained relatively few officers, and most of these were of junior rank. A curious fact is that before the end of the 18th century, the entire EIC army as a whole had no generals and only 10 colonels and 30 lieutenant colonels. This threadbare officer structure saw a captain command a sepoy battalion, a major command a European battalion, and a colonel command a presidency army. This situation reflected the company's priority as a trading body and the desire of its all-powerful accountants to save costs wherever possible.

Recruiting high calibre European officers was difficult since the best were attracted to the regular army, but there were some officers who signed up when their regular army regiment was sent home and they wished, instead, to remain in India. A local wife, a much higher standard of living compared to back home, and a love of adventure were all reasons for army regulars to switch to the EIC army. The EIC never had any problems filling its lower ranks, and as the historian I. Barrow notes, "It is one of the great ironies of the Company's history that its Indian empire was effectively won by Indian troops" (82). This despite the relatively low pay offered by the ever-grasping directors of the EIC. At least soldiers were paid a little extra if they were stationed outside their presidency, and there was always the chance of extra pay after victories in battle as well as a small slice of the taxes the company imposed on merchants who supplied the army. Indian soldiers, especially Hindus from peasant backgrounds, were also attracted by the chance to gain greater status in society.

By 1823, Bombay had 36,475 troops, Madras had 71,423, and Bengal, the most prestigious, had 129,473 (Barrow, 83). The combined EIC army was larger than the British Army in the 1830s and 1840s. The EIC army kept on growing, too, reaching 280,000 men at its peak. These troops were, from 1796, organised into regiments composed of two battalions. In 1824, a single-battalion regiment structure was adopted. The splitting of armies into well-defined units had important consequences. Well-defined groupings allowed a continuous musket fire on the battlefield and made moving troops across it much more efficient. It was these two areas which made the EIC armies superior to that of their enemies.

Challenges

The EIC was well-trained and well-equipped, but that was often, too, the case with its opponents, especially the Sikhs and Marathas. The various EIC territories were also disconnected, which left huge borders to control. The EIC had to overcome several other inherent problems with its military arm. There were rivalries and frictions between different presidency armies, between EIC and regular British troops, between younger but higher ranking British army officers and older, lower-ranked EIC officers (promotion was slow in the EIC and there were fewer top ranks), and between British officers and Indian privates. Finally, British troops suffered more than their indigenous enemies from diseases like dysentery and cholera. Nevertheless, the EIC managed to overcome these problems and present a unified military front when required.

Through military force, control of the sea, massive financial resources, and unprincipled diplomacy, the EIC managed to pull off victory after victory. There were some defeats along the way, and sometimes the company preferred to pay off an equally well-armed enemy rather than fight it, but such was the general trend of victory that the EIC was able to set the stage for the British Empire to take over India.

Weapons & Uniforms

Flintlock rifles were the most common weapon, and the EIC introduced its own pattern musket in 1764. From the mid-19th century, troops were issued with the cartridge-loaded Enfield Rifle. Regular troops carried a bayonet, officers a pistol and a sword. Sergeants traditionally carried a halberd. Artillery had developed in Europe so that now cannons could be more precisely elevated, which in turn gave a much more accurate fire. The usual tactic was to bombard the enemy with artillery, present a series of devastating volley-fire from muskets, and then charge the enemy with fixed bayonets. Cavalry units were employed against enemy cavalry and to protect the vulnerable flanks of the infantry when manoeuvring and the even more exposed artillery units.

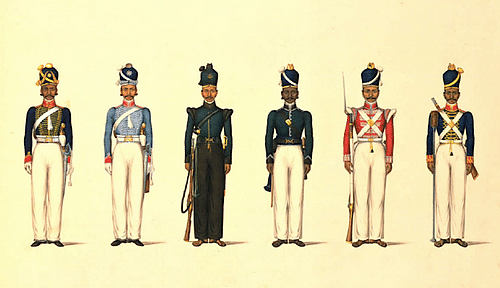

European EIC soldiers wore red coats, white waistcoats, white trousers, black boots, and wide-brimmed hats or topees (pith helmets) until caps or shakos were introduced in the early 19th century. White cross-belts were worn across the chest, which held leather pouches for cartridges at the back. The various presidency troops had different coloured facings (e.g. lapels and cuffs), which changed over time not only within regiments but also battalions. Lace-edged collars, shoulder straps and wings also varied but were white across the presidencies from the 1840s. British cavalry officers often wore the braided hussar jackets commonly seen in European armies of the period. Artillery officers wore dark blue jackets with red facings, and their dress uniform included a helmet with a horsehair plume.

Sepoys wore similar jackets to European soldiers, but their colours varied (red, dark green, dark blue, grey, and khaki amongst others, depending on function and location). Sepoys were distinguished by their jangheas (a type of shorts), alternatively, they wore longer trousers (jodhpurs) or baggier trousers (pantaloons), which were in some periods a badge of rank. Sepoys wore various types of turban, which could carry brass additions such as a front plate of identification, a pointed top or ball, and decorative chin straps. After 1806, false turbans were worn, that is cloth stretched over a bamboo or rattan frame made to look like a turban.

Rebellion

The EIC might have defended its interests against outside rivals, but it was from within that it met its greatest challenge. The Sepoy Mutiny (aka The Uprising or First Indian War of Independence) rebelled against British rule. The causes of the rebellion were many and ranged from discrimination against Indian cultural practices to Indian princes not being allowed to pass on their territories to an adopted son, but the initial spark came from the sepoys. On 10 May 1857, the EIC sepoys protested in Meerut against their much lower pay compared to British EIC soldiers. Indian soldiers were not happy either with the obligation to serve outside India (which would require Hindus to perform costly rites of purification) or the institutional racism that prevented them from ever becoming officers. The final straw was the introduction of greased cartridges for Enfield rifles (the animal fat grease offended Hindu and Muslim beliefs since the cartridges had to be prepared by mouth).

At this point, the EIC employed around 45,000 British soldiers and over 230,000 sepoys. In Bengal, 45 of the 74 sepoy regiments rebelled, and their cause was taken up by a host of Indian princes disgruntled at their poor treatment by the EIC. Although the rebellion spread to much of northern and central India and the sepoys took over important centres like Delhi, their lack of overall command and coordination and the superior resources of the EIC and the British government led to their downfall. To fight the rebels, the regular British Army was used along with loyal Sikh troops and new allies such as the Gurkhas from Nepal. Casualties were high on both sides but far more so on the Indian side, as here summarised by Barrow:

2,600 British enlisted soldiers and 157 officers were killed. Another 8,000 died of heatstroke and disease, while 3,000 were severely injured. Indian deaths from the war and the resulting famines may have reached 800,000.

(115)

The mutiny was quashed by the spring of 1858, and the British Crown took the final step in what had been a gradual process of regulation and control to finally take full possession of EIC territories in India. The EIC navy was disbanded, and in June 1862, the nine EIC's European regiments were taken over, although it was not until 1895 that the various surviving EIC presidency armies were finally united into a single British Indian Army.