The lives of women in ancient Mesopotamia cannot be characterized as easily as with other civilizations owing to the different cultures over time. Generally speaking, though, Mesopotamian women had significant rights, could own businesses, buy and sell land, live on their own, initiate divorce, and, though officially secondary to men, found ways to assert their autonomy.

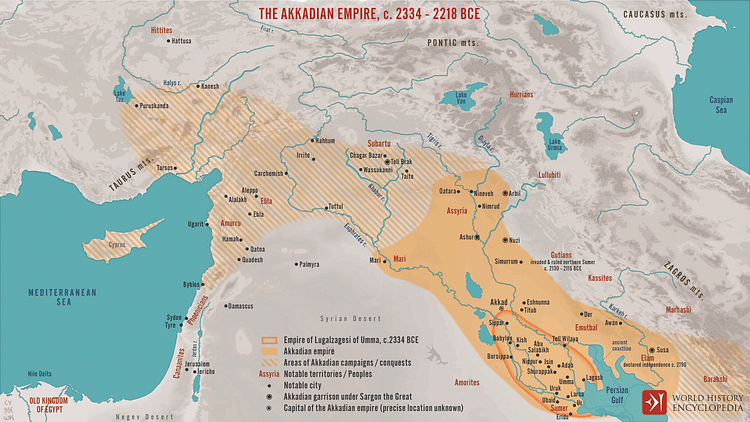

Scholars generally agree that women had the greatest freedoms in the early stages of Mesopotamian cultural development, from the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) through the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) prior to the rise of Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE). It has been noted, however, that Sargon chose a female deity (Inanna/Ishtar) as his protector, installed his daughter Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE) as high priestess of Ur, and records indicate that women still had many of the same rights as before.

The same claim is made regarding Hammurabi of Babylon (r. 1795-1750 BCE) but, while it is true that worship of female deities and women's rights declined under his reign, there is still evidence of female autonomy, and this paradigm continues through the period of the Assyrian Empire (c. 1900-612 BCE) and from the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) to the fall of the Sassanian Empire c. 651 CE. Although the patriarchy sought to control women's rights and personal choices throughout all these eras, women are still recorded as landowners, business owners, administrators, bureaucrats, doctors, scribes, clergy, and in rare cases, even monarchs.

Mesopotamian society, like any other, was hierarchical and divided into five classes – nobility, clergy, upper class, lower class, and slaves – and these are sometimes simplified as three designations: free, dependent, and slave. Women's roles were defined by this hierarchy with elite women at the top and slaves at the bottom. In between was a class of semi-free women, which modern scholars struggle to define clearly, as they were neither completely free nor were they slaves and so 'dependent' seems the term that fits best. These women (and men) were usually attached to a temple in some capacity.

Women continued to be defined, more or less, by this hierarchy and maintained their rights until the fall of the Sassanian Empire to the Muslim Arabs in 651 CE. Afterwards, women's rights declined far more dramatically than any waning under either Sargon or Hammurabi. Some scholars have correlated the decline of women's status to the rise of male deities and a greater focus on heavily patriarchal religious systems, though this claim has been challenged. Even so, after 651 CE, there is a clear decline in women's rights in the region.

Women’s Classification

Women were classified according to their social status (as were men) according to the above hierarchy and terms included:

- free women of the nobility/upper class (awilatum in Akkadian)

- free women of the clergy (some known as naditu in Babylonian)

- female administrators (sakintu in the Neo-Assyrian period)

- free women of the lower class (known by various terms)

- prostitutes and/or single women (harimtu in Akkadian)

- dependents who belonged to no male household (sirkus in Babylonian)

- female slaves (amtu in Babylonian)

The names for these classifications changed with the times and different dominant cultures, but the essential hierarchy remained the same. Women were subordinate first to their fathers and then their husbands (with some exceptions such as clergy or certain wealthy nobility), and, later, their sons. Although individual women could manage to pursue their own path, this was rare, and most lived according to the traditions, rules, and expectations of the patriarchy.

Women’s Status & Marriage

Throughout Mesopotamian history, a woman was expected to marry and bear children she would then raise while tending the house. The exception to this is the naditu women of the city of Sippar c. 1880-1550 BCE, who were priestesses dedicated to a male deity. Even these women were expected to marry, though not bear children, and their husbands took secondary wives. The naditu were attached to the household of the temple, performed duties related to the care of the god, and "engaged in business activities" (Leick, 189).

The only term associated with an unmarried woman of marriageable age is harimtu, which, it seems, could refer to a prostitute or a single woman. The precise definition of this term is still debated, but if applied to a single woman, she was either wealthy enough to live by her own rules or a member of the dependent class – neither free nor slave – attached to a temple. According to the scholar Kristin Kleber, these women (or men) were known in Neo-Babylonian communities of the 6th century BCE as sirkus:

Sirkus are often characterized as temple slaves, and it is generally held that their fate was better than that of other kinds of slaves because the temple gods, as owners, did not directly exercise rights of ownership. I argue that sirkus were not slaves, in fact, but are better understood as institutional dependents whose limited freedom, in comparison with free citizens of a Babylonian town, was a result of their social subordination to an institutional temple household. (Culbertson, 101)

Aside from the naditu and sirkus, a wealthy widow might choose not to remarry, and there were certainly other exceptions to the rule, but, overall, once a young woman was of marriageable age, her father arranged a wedding with an appropriate match considered beneficial to both parties. The marriage agreement was a legal, business contract, having nothing to do with the desires or interests of the betrothed. Scholar Jean Bottero discusses the process:

For a man, marriage was 'to take possession of one's wife' – from the same verb (ahazu) commonly understood for the capture of people or the seizure of any territory or goods. It was the husband-to-be's family who initiated the matter and who, having chosen the girl, after an agreement paid her family a compensatory amount – in short, a transaction which necessarily brings to mind a form of purchase. After this, the girl thus 'acquired', was removed from her own family by the matrimonial ceremony and introduced into her husband's family where, barring accident, she would stay until she died. (114-115)

There were five steps to the process of marriage, all of which had to be observed in keeping with tradition, that had to be observed precisely for the union to be recognized as legal and binding:

- engagement/marriage contract

- payment of the bride price to the father of the bride and of the dowry to the father of the groom

- ceremony and wedding feast

- bride moves to her father-in-law's home

- sexual intercourse the night of the wedding with the expectation the bride would become pregnant

The wife was considered the property of her husband in that she was expected to obey completely and could be divorced and 'put away' if her husband chose and had legal grounds (while it was more difficult for a woman to sue for divorce), but, as in all aspects of women's lives in Mesopotamia, this is understood as a generality. Bottero notes how many women were able to assert themselves and maintain autonomy:

In Mesopotamia, as elsewhere, every woman had up her sleeve two reliable trump cards to stand up to any representative of the so-called 'strong' sex, and even to dominate him, in spite of all the customary or legal constraints: first, her femininity; then, her personality, spirit, and character. And it was up to her to make use of these to swim against the opposing current of the contemporary mindset. (118-119)

This seems to be the case in every era of Mesopotamian history but, at the same time, some periods give evidence of greater equality of the sexes overall than others.

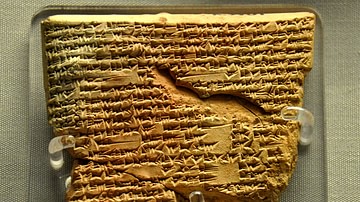

Uruk to Early Dynastic Period

The Sumerians of the Uruk and Early Dynastic periods (and, later, the Ur III Period, 2047-1750 BCE) provide the greatest evidence for women's equality. In the Uruk Period, the cylinder seal was developed, and many from this period belonged to women, suggesting they were legally allowed to sign contracts and enter into business agreements at this time. The Uruk Period also sees the rise of urbanization and the development of writing, both of which make clear that female deities – such as Gula, Inanna, Ninhursag, Nisaba, and Ninkasi among others – were venerated more widely than males.

During the Early Dynastic I Period (2900-2800 BCE), households were associated with the patron deity of the city, which often meant a goddess. Upper-class women had almost equal rights, but lower-class women had few if any (the same applied to men), but during the Early Dynastic II Period (2800-2600 BCE), increased food production led to diversification in the division of labor, providing more opportunities for women as artisans, millers, bakers, brewers, and weavers. Textiles came to be especially associated with women at this time and would continue to be going forward.

During the Early Dynastic III Period (2600-2334 BCE), women's status remained the same or improved. Two women are known to have ruled in their own right during this era: Queen Puabi of Ur (known from her tomb in the Royal Cemetery of Ur) and Kubaba of Kish, the only woman's name to appear as queen in the Sumerian King List (composed c. 2100 BCE). Based on Puabi's cylinder seal and Kubaba's name in the King List, both women ruled on their own without a male consort. Queen Barag-irnun of Umma ruled with her husband Gisa-kidu during this same period and was regarded highly enough to have her name included on the dedicatory plaque in the Temple of the god Sara at Umma.

Social mobility was rare but possible as evidenced by Kubaba, who is listed as a former tavernkeeper. There are few records of women (or anyone) climbing the social ladder, but it is clear that many held positions outside the home – besides notable female monarchs, scribes, priestesses, and doctors – working as artists, artisans, bakers, basket makers, brewers, cupbearers, dancers, estate managers, farmers, goldsmiths, jewelry makers, merchants, musicians, perfume makers, potters, prostitutes, tavern owners, and weavers among other occupations.

Akkadian & Ur III Period

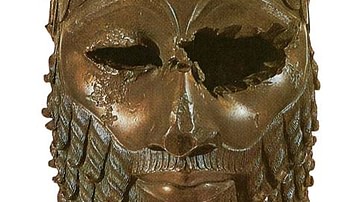

Scholars have noted that this model changed under the Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great and that this is most likely due to his focus on martial strength and conquest coupled with the perception of women as 'the weaker sex' in a time when military might became more highly valued. Sargon, and his successors, campaigned regularly against insurgents and break-away regions, keeping a standing army, which also served as a municipal police force. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek comments:

This must have been a highly militarized society, with armed warriors often seen patrolling the streets, particularly in provincial cities, on whose loyalty the center could not always depend. Sargon wrote that every day 5,400 men, perhaps the nucleus of a standing army, took their meal before him in Akkad. (125)

There are fewer records of women holding important positions, but there are also fewer records overall, and modern-day scholars still do not have any idea where Akkad was even located. It does not seem that Sargon had any interest in suppressing women's rights as he credits his mother with saving him and sending him toward his destiny, invokes Inanna/Ishtar as his personal divine protector, and installed his daughter, Enheduanna, as high priestess of the city of Ur. According to Kriwaczek, offerings to departed priestesses continued to be offered in their honor at Ur long after their deaths (120).

Bottero, and other scholars, cite the Semitic nature of the Akkadian Empire as the reason for women's decline in status, as males (and male deities) were considered superior to females in every way. This paradigm, however, can also be seen in ancient China, Japan, India, Greece, Rome, and beyond without a Semitic association. In Sargon's famous inscription found at Nippur, he first cites Inanna before the male gods Anu and Enlil, and Inanna continued to be venerated during the Akkadian Period. It is therefore more likely that any loss of women's status had to do with a greater value being placed on the traditionally masculine art of war – and deities, usually male, associated with military conquest – as even Inanna is invoked regularly, not as a goddess of love and sexuality, but of warfare.

Babylonians & Assyrians

In the case of the Babylonians, however, the elevation of male gods – especially Marduk – signaled the decline in prestige of female deities and women's status. Under Hammurabi (also a Semitic monarch), female deities were sidelined by males (the goddess Nisaba, to cite one example, was replaced by the god Nabu as patron of writing), and the Code of Hammurabi strictly regulates women's behavior and emphasizes the role of woman as a wife and mother. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

The belief in the centrality of marriage is clearly expressed in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi. Of its 282 statutes, almost one fourth are devoted to family law. (275)

Among the laws were those dealing with infidelity or abandonment of the husband by the wife for another man. In such cases, and especially if the two lovers were found together, they were bound to each other and thrown into the river. When they drowned, this was understood as the just judgment of the gods on two people who had violated the central value of marriage and family. A husband could take as many secondary wives as he could afford, however, or even divorce his wife for another woman without the same sort of risk.

The concept of a woman as wife and mother was nothing new, but under Hammurabi, it became more pronounced at the same time as female deities declined in importance. This has led some scholars to the conclusion that there is direct correlation between women's status and the perceived sex of the deities a community or culture embraces. Even so, it is clear from Hammurabi's Code that women still had jobs outside the home and continued to find opportunities within the confines of the patriarchal system.

This same model is seen in the Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian periods during which the god Ashur rose to such prominence that he eclipsed all others and his worship bordered on monotheism. Still, the city of Ashur – the site of Ashur's main temple beginning c. 1900 BCE – traded regularly with the port city of Karum Kanesh, and women were the central administrators and facilitators of this trade. Female administrators (sakintu) supervised the creation and shipment of textiles between Ashur and Karum Kanesh and corresponded regularly with the men who carried the goods between the two cities as well as the merchants who handled sales.

The great Assyrian queen Sammu-Ramat (r. 811-806 BCE) also lived during this period, and her reign is thought to have been so impressive that she inspired the later legendary figure of Queen Semiramis. The Queen Mother Zakutu (l. c. 728 to c. 668 BCE) is another famous woman of the Neo-Assyrian period who rose from the position of secondary wife of Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE) to Queen Mother of his successor Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE) and grandmother of Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE), famous for her treaty ensuring her grandson's smooth succession to the throne.

Persian Women

Persian women were used to equal treatment beginning at least in the Achaemenid period and, most likely, before. Women in ancient Persia received equal pay for their work (which was not the case elsewhere, not even in Sumer), could travel on their own, could own land and businesses, engage in trade, and initiate divorce without complications. Women in the Achaemenid Persian Empire not only worked alongside men but were often supervisors who were paid more than males for managing greater responsibility. Pregnant women received higher wages, and new mothers, for the first month after the birth of their child, did also.

Women in the Achaemenid Empire, Parthia, and the Sassanian Empire were allowed to serve in the military, conduct business as equals with men, and even lead men in battle. In the Sassanian period, female dancers, musicians, and storytellers attained the status of modern-day celebrities, and it is thought that the Sassanian queen Azadokht Shahbanu, wife of Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE) was the power behind the establishment of Gundeshapur, the great cultural center, teaching hospital, and library.

Conclusion

The Sassanian Empire fell to the Muslim Arabs in 651 CE, and women's status in ancient Mesopotamia declined sharply. This was partly due simply to the conquerors' attempts at subduing the values of the conquered, as happens in any such situation. In the case of the conquest of Mesopotamia, however, this suppression of the region's values had a direct correlation to the religion of the conquerors and conquered pertaining to women's status. The Persian goddess Anahita, though no longer regarded as a deity in her own right and more as an avatar of Ahura Mazda, the supreme deity of Zoroastrianism, was still widely venerated at the time of the conquest and had continued to provide women with a strong image of the divine for centuries.

The Muslim Arab conquest toppled Anahita and other divine feminine figures such as Cybele – the Anatolian mother goddess thought to have been inspired by Queen Kubaba or the semi-divine Semiramis – who were then replaced by the supreme male deity Allah of Islam. This same pattern is evident elsewhere, according to scholars in line with Kramer and Spencer, when patriarchal monotheistic belief systems dominate earlier polytheistic beliefs that celebrate the feminine principle, women's status in society inevitably suffers and equality is lost.