The assassination of revolutionary activist and Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat on 13 July 1793 was one of the most iconic moments of the French Revolution (1789-1799), immortalized in Jacques-Louis David's painting Death of Marat. Marat's killer, Charlotte Corday, believed that the only way to save the Revolution and prevent the excesses of the Reign of Terror was through his death.

The murder failed to prevent the Terror, instead giving the Jacobins a martyr who they could use to advance their agenda. Following her execution four days after the assassination, Corday also became a symbolic figure for those who resisted the Jacobin regime. In the decades since the event, it has become mythicized through the various poetry, art, and literature made about it.

The Pariah: Jean-Paul Marat

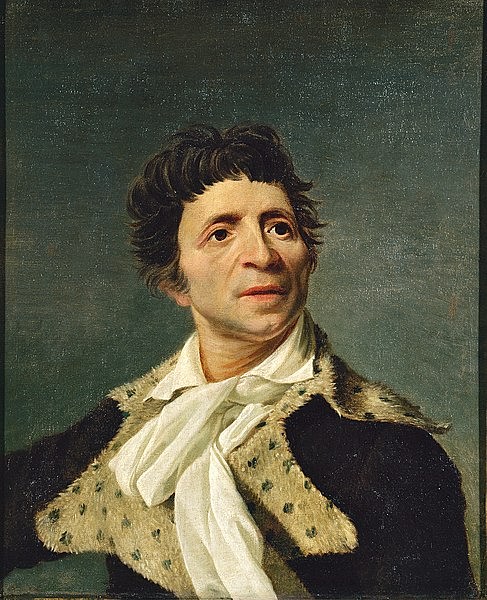

On the topic of Marat, historian Mona Ozouf makes an interesting observation: "The historiography of the French Revolution has had its Dantonists. It always has Robespierrists. But it has few Maratists" (Furet et al, 244). Truly, even amongst the colorful cast of characters found in the French Revolution, Marat stands out as unique, an outcast in death as he was in life. Short in stature, Marat was ugly and extravagant, a former physician who had failed to break into the social circles of aristocratic society, turning instead to a life of provocation, encouraging the most extreme excesses during the course of his revolutionary career. He has been described as a "streetcorner Caligula" by Chateaubriand, and a "functionary of ruin" by Victor Hugo (ibid). To his supporters, he was always a patriotic visionary, a true friend of the people. To his detractors, he was a pestilence, leaving murder and destruction in his wake.

This heavily divisive man was born in Neuchâtel, Switzerland, on 24 May 1743. He came to France to pursue a career as a physician, writing papers on scientific and philosophical topics. As early as the 1770s, he was making attacks against the aristocracy; in his earliest political work, the 1774 Chains of Slavery, he wrote of a supposed aristocratic plot against the people, something that would become a running theme throughout his work. Ozouf reiterates the idea that Marat's later violence came about in this phase of his life when his intellectual ambitions were thwarted again and again. When the Revolution began, Ozouf states, it offered him "an unprecedented promise: the ability to avenge slights received or imagined and thereby avenge humanity" (Furet et al, 246).

Marat was hardly the only one who felt downtrodden by French society in the years leading up to Revolution. It was from this large crowd of poor, hungry, marginalized people that he drew his audience. Publishing the first issue of his famous newspaper, L'Ami du Peuple ("Friend of the people") in September 1789, Marat quickly became renowned for his colorful, inflammatory remarks and fiery attacks on public officials; at one point in 1790, his attacks against chief royal minister Jacques Necker became so virulent that a warrant went out for his arrest, forcing him to go into hiding.

It is difficult to quantify the exact impact Marat had on the Revolution, seeing as he rarely took active participation in events, preferring instead to write about them before or after their occurrences. Certainly, he took pleasure in unmasking the Revolution's enemies, priding himself on his predictions of Lafayette's treason or Mirabeau's corruption. He also advocated for political violence as a means to an end, famously stating that "six hundred well-chosen heads" would deliver liberty to France. He often spoke of the need to purge certain individuals for the greater good and would routinely call for violence against "counter-revolutionary" figures.

Eventually, as his newspaper expanded in popularity, Marat's influence could be found at the heart of several of the Revolution's bloodiest moments. These included the Storming of the Tuileries Palace, which overthrew the monarchy, and the September Massacres, in which between 1,100 and 1,400 clergymen and political prisoners were butchered by Parisian mobs. He had called for all good patriots to go to the prison of Abbaye, take the priests and Swiss Guards imprisoned there, and "run a sword through them" (Schama, 630).

By late 1792, Marat was popular enough to win a seat in the National Convention, and a few months later he served as president of the Jacobin Club. In April 1793, he was arrested by the Jacobins' rivals, the moderate Girondin faction, who hoped to use him as an example to their enemies. Marat was charged with inciting violence and put on trial on 24 April. Unexpectedly, large crowds came to support him as Marat eloquently defended himself by claiming the statements used against him had been taken out of context.

He was acquitted, a rarity for those placed before the Revolutionary Tribunal, to the delight of the cheering crowd, who hoisted him upon their shoulders and placed a crown of laurel on his head. Marat would not have to wait long to have his revenge. A little over a month after his trial, he was instrumental in inciting the insurrections that led to the fall of the Girondins on 2 June. By the summer of 1793, it seemed Marat was at the height of his influence, an outcast no longer, with no one left to stand in his way, except a provincial young woman from Normandy.

The Assassin: Charlotte Corday

Charlotte Corday was born in Saint-Saturnin, Normandy on 27 July 1768. At 13 years old, she was sent to live in a convent in Caen following the death of her mother. There, she would become enraptured by the works of philosophers of the French Enlightenment such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire. By the start of the Revolution, she was an avowed republican, despite the aristocratic background of her family.

By 1793, Corday found herself disgusted by the direction the Revolution was heading. News of the September Massacres had particularly horrified her, and political violence had found its way to her hometown of Caen; in April, Abbé Gombault, the refractory priest who had given last rites to Corday's dying mother, was the first to be guillotined in Caen. Corday, who lived a short stroll away from the local Girondin headquarters, came to blame the violence on the Jacobins, who had long encouraged the Parisian mobs in their insurrections. She would have been further influenced by the militant atmosphere in Normandy, which was preparing to rebel against the Jacobin regime, the way other cities recently had in the Federalist Revolts. The Girondist pamphlets circulating Caen were equally as inflammatory as those of the Jacobins, which may have helped Corday choose her target. One such pamphlet read:

Let Marat's head fall and the Republic is saved…Purge France of this man of blood…Marat sees Public Safety only in a river of blood; well then, his own must flow, for his head must fall to save two hundred thousand others (Schama, 730).

Using logic eerily similar to Marat's own, Corday came to the conclusion that Marat had to die so the Republic could live. On 9 July, she left Caen for Paris, arriving two days later. On the morning of 13 July, she visited the gardens of the Palais-Royal and purchased a kitchen knife with a wooden handle and a five-inch blade. Slipping it beneath her dress, she made her way to Marat's apartments on the rue des Cordeliers.

The Murder

Corday had hoped to kill Marat in full view of the National Convention to maximize the impact of her message, but shortly before her arrival in Paris, Marat suffered the resurgence of a nasty skin condition that had been intermittently bothering him for two years. Confined to soaking in his bathtub, Marat was visited by the painter and Jacobin supporter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) the day before his death. David found his friend in good spirits and hard at work, using a plank laid across his tub as a writing desk. The bathroom was adorned with maps of the Republic and revolutionary slogans. When David wished Marat a speedy recovery, the sick man laughed. "Ten years more or less in the duration of my life do not concern me," he said. "My only desire is to be able to say with my last breath 'I am happy the fatherland is saved'" (Schama, 731).

At 11.30 the following morning, Charlotte Corday arrived at the doorstep of Marat's apartment, requesting a visit with the famous Friend of the People. She was met by Catherine Evrard, sister of Marat's fiancée Simonne, who refused her entry, claiming Marat was too sick to receive any visitors. Corday gave Catherine a letter about a supposed Girondist conspiracy in Caen before taking her leave. She returned at seven in the evening, sneaking into the apartment as a delivery of fresh bread was being made. This time, she was stopped on the stairs by Simonne herself. Suspicious of this stranger's determination to see Marat, Simonne attempted to turn her away again. As they argued, Corday deliberately raised her voice so that Marat could hear in the next room, claiming she wished to give him information about traitors in Normandy. Before Simonne could push her back down the stairs, a voice sounded from the bathroom: "Let her in."

Reluctantly, Simonne led Corday into the room where Marat was soaking in his bath, a wet cloth tied about his brow. He invited Corday to take a seat by his tub while Simonne waited at the corner of the room, keeping a close eye on the visitor. For 15 minutes, they talked about the political situation in Caen before Marat sent Simonne out of the room to fetch him a fresh solution for his bathwater. Once she was gone, Marat asked Corday for a complete list of the conspirators. According to Corday, once she had listed the names, Marat had said, "Good. In a few days I will have them all guillotined" (Schama, 736).

That was when the assassin struck. Reaching into her dress, Corday produced the kitchen knife which she plunged into Marat's right side, just below the clavicle. He screamed in pain, shouting, "Help me, my beloved!" By the time Simonne rushed back into the room she found Marat floating in a tub of reddened water, and the girl standing beside him. Simonne screamed, "My God, he has been assassinated!", and turned to Corday, "what have you done?" (Schama, 737).

Marat's dying scream was heard by his neighbors who now rushed in to help. One man, Laurent Bas, who distributed Marat's newspaper, hurled a chair at Corday before tackling her and pinning her to the ground. Two of the neighbors, a dentist and a surgeon, lifted the body from the tub to try and staunch the bleeding. But it was too late. The Friend of the People was already dead.

News of the attack traveled quickly, and within the hour a large crowd had gathered outside Marat's apartments. Six deputies from the National Convention arrived to interrogate Corday, who had made no attempts to escape or resist arrest. She answered every question put before her, claiming she had come to Paris with the sole intention of killing Marat, and that she had done so of her own volition, aided and abetted by no outside parties.

The Jacobin leadership, convinced of a grand Girondist plot, had Corday cross-examined by the Revolutionary Tribunal three times over the next four days. Each time, Corday proudly insisted she had acted alone. When asked why she had killed Marat, Corday answered, "I knew that he was perverting France. I have killed one man to save a hundred thousand... I was a republican well before the Revolution, and I have never lacked for energy" (Andress, 189). She remained unrepentant, believing she had done France a patriotic service. On 17 July, Corday was executed by guillotine, only ten days before her 25th birthday.

Two Martyrs

The assassination of Marat would hold significance for both sides of the revolutionary divide. For some, it was the deliverance of justice, a vile creature aspiring to dictatorship struck down by the virtuous hand of a youthful maiden. For others, it was a tragedy, the friend of the people slain in his own bathtub by a traitorous aristocrat. In time, both Marat and Corday would achieve the status of martyrs, one for the Jacobins, the other for those who resisted them. A far cry from Corday's desire to lessen the bloodshed and diminish Jacobin influence, her act only served to deepen divisions in the months preceding Jacobin supremacy and the Reign of Terror.

Marat's martyrdom took place almost immediately. In the weeks leading up to his assassination, his fellow Jacobin leaders had become mistrustful of him, nervous that he would turn his populist rhetoric against them. Now, they took steps to maximize their political gains from his death. The funeral ceremonies were organized by the esteemed painter David, who paid 7,500 livres for the best embalmer in Paris to prepare Marat's body. It was a demanding order; the fatal wound had to be emphasized to show the suffering of Marat, while his disfiguring skin condition had to be covered up. In the end, it hardly mattered. The stifling summer heat caused the corpse to stink so bad that they were forced to hold the funeral days early, meaning most of France's prominent officials were unable to attend.

However, this unfortunate funeral did not stop an almost cultlike reverence to surround the murdered Marat. His heart was removed and placed in an urn that hung above the radical Cordeliers Club. At the ceremony commemorating this, a eulogy was given by the Marquis de Sade, which demonstrated the increasingly anti-Christian nature of the Revolution by comparing Marat to Jesus Christ:

O heart of Jesus, O heart of Marat…their Jesus was but a false prophet, but Marat is a god. Long live the heart of Marat…Like Jesus, Marat detested nobles, priests, the rich, the scoundrels. Like Jesus, he led a poor and frugal life… (Schama, 744).

Popular songs were written in the name of the 'patriot Marat', as his bust replaced a statue of the Virgin Mary on the rue aux Ours. For a time, the port city of Le Havre even changed its name to Le Havre-de-Marat, and when the Jacobins eventually established their own Cult of the Supreme Being to replace Christianity, Marat was made a quasi-saint. His remains were interred in the French Panthéon in 1794, and the Jacobins used his martyrdom to push through their own agenda. As historian Simon Schama points out, the unpredictable, chaotic Marat was more use to them in death than in life.

The downfall of the Jacobins and the Thermidorian Reaction, however, ended this deification of Marat. In 1795, his busts were smashed in the streets, and his coffin was removed from the Panthéon. While Marat would enjoy a brief resurgence of post-mortem popularity in the early years of the Soviet Union, he had truly become an outcast once again.

Charlotte Corday would also become a martyr, for the opposite side. She became a symbol of resistance to the Jacobins; the green headdress she wore on the day of the murder would help make green the color of counter-revolution throughout France. Although many feminists at the time reviled her for her actions and for potentially causing the executions of leading revolutionary women like Madame Roland, Corday played an important role in the conversation surrounding women in the French Revolution. By committing her act alone, without the coercing of a man, she proved that women were capable of self-autonomy and of committing political acts. She became romanticized in paintings, poems, and literature. In 1847, writer Alphonse de Lamartine even assigned her the nickname 'Angel of Assassination'.

In Art & Popular Culture

Both Marat and Corday sought to achieve revolutionary ideals through acts of violence. Both of them became heroes and martyrs for their respective ideologies. And both continue to survive to this day, in the form of art. As part of the Jacobin propaganda machine, Jacques-Louis David made a painting of his fallen friend that would become one of the most famous works of art to come out of the Revolution. In it, Marat lies dead in his bathtub, his features beautified and his expression peaceful. It is widely considered to be David's masterpiece and is often reproduced for its historical and cultural significance. Corday, too, was painted, by the National Guard officer Jean-Jacques Hauer in the last hours of her life. Behind the innocence of Hauer's Corday is a certain unapologetic determination, the face of one who believed herself to be a patriot.

Aside from countless other paintings, Marat and Corday have both been featured in novels and poems throughout the centuries. Marat features in Victor Hugo's novel Ninety-Three, while Corday is briefly referenced in another of his famous works, Les Miserables. Numerous plays and operas have been made about the assassination, including the relatively recent Charlotte Corday written by Italian composer Lorenzo Ferrero in 1989 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Revolution. References to the assassination have even made their way into video games; in the popular 2014 game Assassin's Creed: Unity, the player must solve the mystery of Marat's murder, which results in the capture and confession of Charlotte Corday. Clearly, Marat's assassination has had a major impact on cultural history just as much as it did on the course of the Revolution itself.