The 1905 Law of Separation of Church and State was enacted as the climax of decades of conflict between monarchists and anticlerical Republicans who viewed Christianity as a permanent obstacle to the social development of the Republic. The law ended the 1801 Concordat between Napoleon and the Vatican, disestablished the Catholic church, and declared state neutrality in religious matters.

France’s Religious Struggle

Following the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, France experienced interminable religious controversy and religious wars. Many believed that a better society would be formed on a foundation that excluded religion and divine authority. The Napoleonic Concordat in 1801 with the Vatican was a step toward societal stability and recognized the legitimacy of other religious expressions alongside the Catholic Church. Although there were no longer wars of religion, soon voices were calling for the end of the Concordat, the separation of Church and State, and a secular nation founded on revolutionary principles.

At the end of the 19th century, the battle for the secularization of France accelerated, and a decisive step needed to be taken. In 1901 the Law of Associations placed the authorization of Catholic teaching orders under the control of the State. The Catholic Church’s influence in education was weakened and the way was prepared for the 1905 Law of Separation of Church and State. The law of 1905, prepared in a passionate climate, was preceded by the rupture of diplomatic relations with the Holy See which rendered the maintenance of the Concordat status quo impossible. The situation of ecclesiastical institutions throughout France was turned upside down. Often presented as an agreement, the law was an act of force that rescinded the 1801 diplomatic convention. In exchange for an independence the Catholic Church was not seeking, the law deprived the Church of its patrimony and removed state subsidies for ministerial salaries.

Prelude to Separation

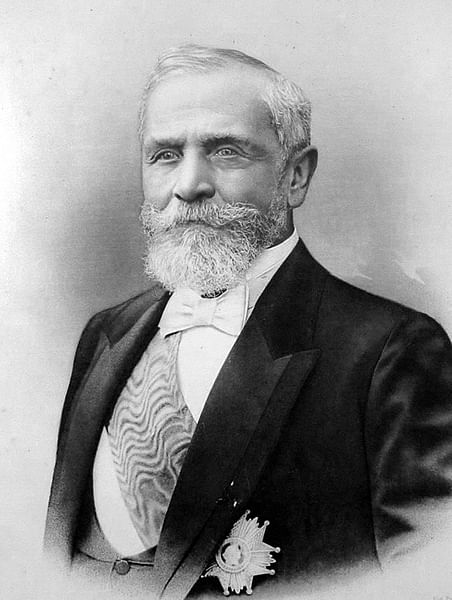

Events in the winter of 1904 contributed to a rupture in relations between France and the Holy See. The rupture originated with a voyage to Rome planned by President Émile Loubet (l. 1838–1929). There had been rumors and discussions on whether the president would request a meeting with Pope Pius X (l. 1835–1914) who was more traditional and inflexible than his predecessor Pope Leo XIII (l. 1810–1903). The president initially signaled his intention to request an audience with the pope. Pius, however, tied any proposed visit to the necessity of discussing the expropriation of Vatican lands from 1860 to 1870 by the Italian government which led successive popes to consider themselves prisoners in the Vatican. In March 1904 the pope addressed the cardinals at the Vatican and criticized the French government. A stalemate ensued between France and the Vatican that was soon aggravated by the president’s voyage which now excluded any audience with the pope.

The president’s voyage to Naples and Rome, Italy, took place in April 1904 where he met with King Victor-Emmanuel III (l. 1869–1947). Together on the palace balcony, they responded to the crowd’s acclamation. The Vatican took offense at the presidential rebuff and indicated that a protest would be lodged against the president’s visit. Three weeks after President Loubet’s voyage to Italy, Rome sent a letter to foreign governments through their diplomatic representatives concerning the French president’s visit to Rome. The letter might have remained an affair among diplomats had Jean Jaurès (l. 1859–1914) now obtained a copy which he published in the newspaper L’Humanité on 17 May 1904. The public revelation of the letter resulted in the recall of the French ambassador from the Holy See, the first major step toward the rupture of diplomatic relations. The pope’s letter revealed that he considered the French president’s trip to Rome and visit with King Victor-Emmanuel III a serious incident over which he took great personal offense. He reminded his readers that Catholic heads of State held special ties with the pope and that government leaders should exercise toward him the same respect accorded to sovereigns of non-Catholic States.

The pope’s criticisms of the French president and accusations of hostility toward the Vatican would not go unanswered. Jaurès contended that the letter was an insolent provocation to both France and Italy. In his view, the pope had not hesitated to accuse the French Republic and its president before other governments. This was considered a declaration of war by the papacy on modern Italy and the Revolution. As a result, Jaurès envisioned the necessity of breaking diplomatic relations between France and the papacy. He declared that the complete emancipation of France, finally rid of all political interference from the Church, now appeared as a national necessity. Politicians, particularly those of the extreme Left, clamored for the immediate termination of the Concordat following the publication of the pope’s letter. The conflict with the Vatican revealed the incompatibility which existed between the traditional Church and the democratic State. This incident presented the opportunity to liberate the State from all religious influence.

On 2 August 1904, Jean Jaurès published a speech in L’Humanité arguing that democracy and secularization were identical. According to him, democracy assured complete and necessary freedom for all consciences, for all beliefs, and for all religions. No religious dogma, however, could become the rule and the foundation of social life. In his opinion, democracy did not require a newborn to belong to any confession, did not require citizens to belong to any religion to guarantee their rights, and did not ask the voting citizen to which religion he or she belonged. He concluded that if democracy was founded outside of all religious systems, if democracy was guided without any dogmatic or supernatural intervention, and if democracy expected development only from the progress of conscience and science, then democracy would be secular in its essence and its forms. A corollary to this reasoning was that education must be constituted on secular foundations. Later that month, on 15 August, Jaurès published an article in La Dépêche du Midi maintaining that it was time for the problems between the Church and the State to be finally resolved (Bruley, 153). For the first time, a timeframe was proposed for a vote on separation early in 1905. The separation would not be decided until December 1905, but the direction of the government and the urgency of action became clear.

Separation Impending

A speech considered decisive in the movement toward separation was given by Council President Émile Combes (l. 1835–1921) in September 1904. He declared that the religious authorities had shredded the Concordat and he did not intend to patch it up. His understanding of the political system entailed the subordination of all institutions to the supremacy of the republican and secular State, in other words, the complete secularization of society. Combes described the opposition to the Republic from royalists, Bonapartists, nationalists, and clericals, the latter considered the most insidious and the most to be feared. The 1901 Law of Associations had been the first step to freeing the nation from religious control. For the past century, according to Combes, the French State and the Church lived under a Concordat regime that never produced its natural and legal effects and had only been an instrument of combat and domination.

The French government warned the Vatican of the serious consequences of continued violations of the Concordat and demanded that the Vatican confirm whether it would submit itself to the obligations of the Concordat. When the government received no response from the Vatican, Combes informed the Vatican that diplomatic relations were broken and expressed his wish that the separation of Church and the State might inaugurate a new and lasting era of social harmony in guaranteeing genuine liberty to religious communities under the uncontested sovereignty of the State.

Opposition to Separation

A preliminary proposal for the separation was adopted by the government’s Council of Ministers. In response, Protestant theologian Raoul Allier (l. 1862–1939) wrote a series of articles that had a great impact in shaping public opinion and have become an important source in the history of the separation. Protestants viewed the project as harmful to Protestant churches, a project which would result in a new wave of persecution. Two Jewish rabbis weighed in with their perspectives on the proposed document. Rabbi Zadoc Kahn (l. 1839–1905) expressed his reservations about ending the Concordat, fearing that it would threaten national unity. Rabbi J. Lehmann (l. 1843–1917), director of the Jewish seminary, expressed his concern for religious edifices and religious traditions. With only 100,000 Jewish adherents in France and French territories, the desire was conveyed to continue to live peacefully under current laws as a minority religion.

Albert de Mun (l. 1841–1914), an anti-Republican deputy, vigorously opposed the separation of Church and State. As a Catholic, he regarded the proposed law as contrary to the teaching of the Church. As a Frenchman, he deemed the law in absolute opposition to all the traditions of the ancient Catholic nation and destined to lead the nation to interior and exterior decline. There was fear that the separation would lead to persecution against the Catholic religion which had already suffered from the forced closure of religious teaching orders. Religious war was envisioned as a consequence of the law and in the end, the State and the Church would need to enact another treaty. In the meantime, Mun exhorted Catholics to remain firm and to begin preparation for sacrifices required in a separation described as a “mirage of liberty” (Mun, 64). The bishop of Nancy, Monseigneur Turinaz (l. 1838–1918), explained the reasons for which the Church would fight against the project of separation. The bishop feared the State would take church property without indemnification. He affirmed that the form of government was unimportant to him and that he did not fault the Republic. His opposition was toward governmental decrees and actions done in the name of the Republic.

Support for Separation

Paul Lafargue (l. 1842–1911), son-in-law of Karl Marx, supported the abrogation of the Concordat and the proposed separation of Church and State. He believed that the Church would be impacted both in its prestige and economically. He refuted the idea that State subsidies for religious institutions and salaries for the clergy were the nation’s debt to the clergy for confiscations of property and possessions during the Revolution. Lafargue claimed that it was not the nation, but the bourgeoisie which had dismembered and cornered for themselves the lands of the Church and that the revolutionary bourgeoisie, in seizing the possessions of the clergy, had only robbed the robbers. Christianity was described as a constitutional illness that the bourgeoisie had in its blood. He lamented that the revolutionaries of 1789, in the ardor of the battle, had pressed on too quickly in their promise to dechristianize France, and the bourgeoisie was victorious.

Anatole France (l. 1844–1924) published L’Église et la République in January 1905 at the time Parliament was beginning its deliberations on the project of separation. In chapter eight he raised and responded affirmatively to the question, “Must the State separate from the Church?” (France, 91–100). It was argued that the progress of civilization in nations determined a clear distinction between civil and religious spheres. The Concordat was seen as a danger to the State. He related a story from his childhood when he was questioned about his religion for a census. France initially responded that he did not belong to any religion. The census taker prodded him to choose a religion anyway so the form would be complete. When France announced that he was Buddhist, the perplexed census worker replied that there were only three columns to choose from and Buddhism was not among them. For France, that response indicated that the State only recognized three forms of the divine and he regarded as unjust the fact that citizens had to subsidize a religion they did not practice. In reality, “due to the Concordat, the secular State believed and professed the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman religion” (99).

Separation Voted

Émile Combes resigned in January 1905 and was not able to see his project of separation come to term. A new government was formed under Maurice Rouvier (l. 1842–1911) and continued the march toward separation. The commission listened to many views on separation in seeking the most suitable solutions to confer all liberties and independence compatible with the rights of the State and the preservation of public order. Since the Vatican opposed any reform or changes in the status of the Catholic Church in France, a considerable and often decisive power for action was given to sociologists, Jews, and especially Protestants. Protestants found themselves at the forefront of efforts to fight in the name of all churches. They pursued the task to militate for a law as judicious and as liberal as possible.

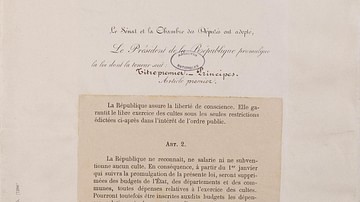

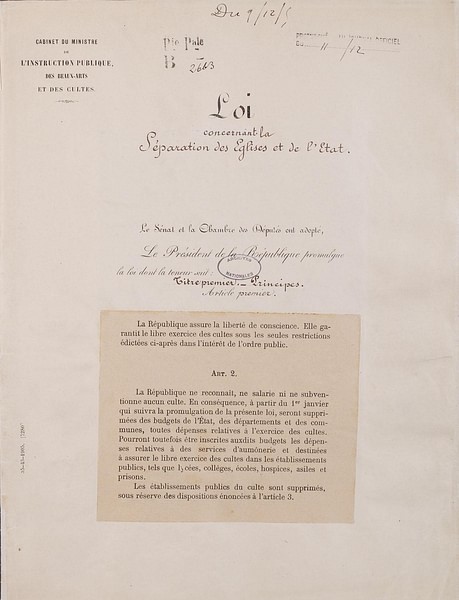

On 6 December 1905, Combes, now a senator from Charente-Inférieure, spoke for the democratic Left in expressing their decision to vote for the law as received from the Chamber in the interest of the law’s implementation taking effect on 1 January 1906. The Senate proceeded to vote and approved the law by 181 for and 102 against. There was an amendment to modify the title of the law, which was rejected. The original title was retained: "Loi du 9 décembre 1905 concernant la séparation des Églises et de l'État" and originally contained 44 articles. The Law of Separation was signed by President Loubet on 9 December 1905. Article one stated that the Republic ensured the freedom of conscience and guaranteed the free exercise of religion with restrictions only in the interest of public order. Article two stipulated that the State neither recognized nor subsidized any religion with exceptions for chaplains in public institutions. Subsequent articles dealt with the disposition and distribution of religious properties to associations and the State.

Although the Law of Separation settled the religious question juridically, religious questions did not go away. The application of the law created unforeseen issues, diverse interpretations, and did not end the contentiousness between the Catholic Church and the State. The majority of French citizens remained Roman Catholic, if only in name and by tradition. The law was not negotiated with the Catholic Church and was perceived as an aggressive move against the Church. Protestants largely welcomed the Law of Separation which legally placed them on the same level as the Catholic Church.

Conclusion

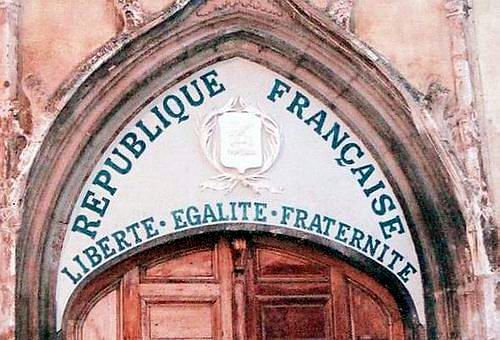

The 20th century presented challenges to the Law of Separation, modifications of the law, and new laws to clarify the law of 1905. After several years the Catholic Church accepted and adapted to its new status. There was no turning back to the former state of affairs. The battle for a secular State had been won. The Catholic Church would never again share power with the State. Rulers would never again govern by divine right. Dominique de Villepin (l. 1953–), former French Prime Minister (2005–2007), summarizes the importance of the Law of Separation:

The long path which led to the separation of Church and State flows directly from the inspirational philosophy of the rights of man of 1789...One principle is at the heart of the law of 1905 - Liberty. The law established a direct line between secular society and the revolutionary ideals affirmed in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. No longer would any religion prevail in exercising any influence on State decisions.

(Villepin, 8).