Psychological intimidation in military conflict has been an art of war since ancient times. Employing misinformation, feigned movements, subtle messaging, and overt display of aggression, its employ is meant to unnerve the enemy before engagement. Surena, the Parthian commander, used it brilliantly against Rome's Crassus, before and during the Battle of Carrhae, in 53 BCE.

Rome's Collision Course with Parthia

After its eventual consolidation of the Italian and Iberian peninsulas; then subduing Greece and parts of North Africa; next, conquering Anatolia and the eastern provinces, including Pontus; and Syria in Palestine; then Gaul (all in the latter half of the first millennium BCE) Rome began to eye control of Mesopotamia and its silk road markets. But there was a huge obstacle in its way: Parthia. The Parthian Empire was itself immense, and its income considerable. Ruling from 247 BCE to 224 CE, its territory stretched from the Mediterranean in the west to India in the east. With its kings Mithridates I conquering; and Mithridates II expanding and consolidating, the Parthians conquered much of the area once held by the Seleucid Greeks. Most importantly – central to former Babylonian, Persian, and Seleucid interests – the Parthians took over the all-important fertile crescent area of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers known as Mesopotamia, including the Silk Road that ran east and west through Mesopotamia. This highway solidified Parthia's position as an international trader. With such commercial expansion, the Parthians became extremely rich – a wealth the Roman commander Marcus Licinius Crassus (115-53 BCE) coveted.

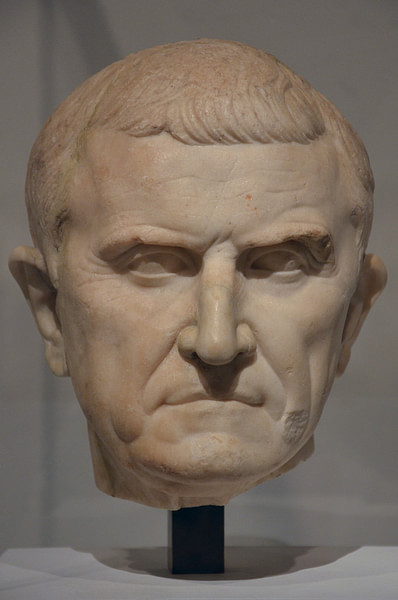

Crassus

At Rome, as two consuls were usually elected to one-year terms by the senate, at the end of the Republican period Crassus, Julius Caesar, and Pompey formed the First Triumvirate to promote their own political interests over senatorial decree. Of the three, though Crassus achieved some martial success of his own (he decimated the slave rebellion of Spartacus), Caesar and Pompey were more famous for their military accomplishments. By 53 BCE, Caesar had gains in Gaul and success in Britain, while Pompey's height of accomplishments was his defeat of Mithridates the Great of Pontus. Yet, besides his considerable political sway at home, known as the richest man in Rome, Crassus possessed a substantial portfolio of land and wealth. Still, as he felt he was living in the shadow of Pompey and Caesar's martial fame, he wanted more. Aware of Parthia's wealth to the east, without senate sanction, Crassus made designs on Parthia. His intent was twofold. If met with success, defeating Parthia would give him wealth beyond imagination and the military fame he coveted. The person he would meet in battle would be the brilliant Parthian commander, Surena (84-53 BCE).

Surena

Under a different system of governance, one of checks and balances between the king and nobles, where the role of the king was essential and respected but answerable to the nobles, especially if he failed in his duties or ruled irresponsibly, Surena was the leading noble of his day. Born of the house of Suren, who, it is thought, owned considerable swaths of land in what is present-day southeastern Iran, Surena was considered the wealthiest of Parthians, next to the king. About Surena, Plutarch says:

In valor and ability, in stature and personal beauty, he had no equal. He used to travel on private business with a baggage train of a thousand camels, a thousand mail-clad horsemen, and still a greater number of light-armed cavalry. Moreover, he enjoyed the ancient and hereditary privilege of setting the crown upon the head of the Parthian king. And though at that time he was not yet thirty years of age, he had the highest reputation for prudence and sagacity. (Crassus, 21.6-7)

With Roman troops in tow, this was the kind of person Crassus would be up against in his bid to take over Parthia.

An Unequal Field?

As a professional, well-trained army, the Romans were known for maintaining tight formations even under duress. Their legions, each with a standard to rally behind, of 4000 to 5000 soldiers, organized themselves into cohorts of 400 to 500 soldiers. However, their troops were trained to adapt to field circumstances. They could form into individual maniples, phalanxes, hollow squares, or the testudo (turtle), a siege technique of raised overlapped shields to repel the rain of missiles thrown from city walls. Their tactics included throwing armor/shield-piercing pilum: javelins that would bend or break on impact so they could not be thrown back. Each soldier was protected with a standard helmet, laminar armor, shin guards, and a scutum: a large shield that provided personal protection against pikes, arrows, and swords and, when interlocked with other shields, served as a moving wall to mow down enemy resistance. Finally, while slingers, archers, and cavalry were supplemental, the weapon of choice was the gladius, a short, broad, double-edged sword used to stab and slash between and around their shields. Such a juggernaut of force was irresistible and gave the Romans their many victories.

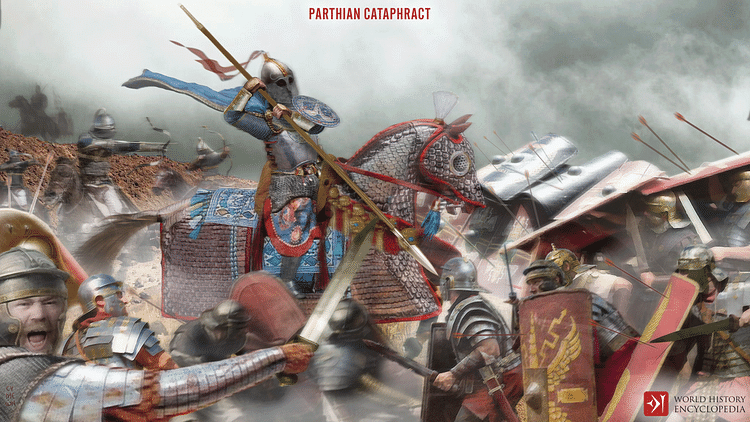

In contrast, Parthian warfare was completely different. With a unique hit-and-run style, their tactics (including pretending retreat) were suited to counter concentrated troop movements. With archers on the fleetest of horses, and camel riders providing a steady supply of arrows, they could make sitting ducks of infantry unable to engage except at close range. When the opponent's cavalry did give chase, the Parthians had an answer. So adept at their lethal craft, they developed the ‘Parthian shot.' Able to shoot backward from the lap of a horse at full gallop, the Parthian archer delivered kill shots at pursuing cavalry. This way, Parthian horsemen came at enemy troops from all directions, creating confusion and wreaking havoc. Finally, their heavy armored horse cavalry (the Parthian cataphract) provided offensive support and assisted in mopping up remaining pockets of resistance with long lances and swords.

Before the battle, the field numbers for Rome were around 30,000 heavy infantry, 4,000 light infantry, and 4,000 cavalry against Parthia's 9,000 horse archers and 1,000 cataphracts. With those numbers, one would think it would be a no-contest for Rome. Nonetheless, it was the art of psychological intimidation at which Surena was expert, which aided Parthia mightily. After all, Surena came from a country already practiced at it. For example, while the Parthians ruled liberally over a wide range of cultures, they still performed subtle messaging on a regular basis. Their ‘diplomacy first; military consequence if necessary' message was a common theme. As their rulers hung long scabbards of swords about their waists and set themselves apart with a festooned display of loose-fitting clothing with multiple horizontal pleats their statues show nobles thus dressed and armed but waving in a friendly manner. Similarly, a popular image on their coins shows the king seated on his throne benignly holding out a bow, flat, not drawn with an arrow, but strung and ready to go - if necessary. Their diplomacy-first policy was also tried on the Romans. Before Crassus made his unprovoked attack on Parthia, Parthia made peaceful overtures. Even when Crassus was in Syria on his way into Parthia, king Orodes II (r. 57-37 BCE) "sent envoys to censure him for the invasion and ask causes of the war," to which Crassus answered, "he would tell him in Seleucia [Parthia's westernmost capital city] the causes of the war." To this, the lead envoy laughed and said, pointing to the palm of his upturned hand, "O Crassus, hair will grow there before thou shalt see Seleucia." Moreover, to place a seed of doubt, Orodes prefaced his message that they already knew Crassus' invasion was unpopular in Rome. (Cassius Dio, 40.16; Plutarch, 18.1-2) Such craft would prove effective for Parthia before and during the battle at Carrhae. Nevertheless, to make matters worse for the Romans, circumstances of weather combined with Crassus' bungled decisions and statements made the perfect storm of self-doubt for his troops. As a result, they would be psychologically shaken before they got to Carrhae.

Crassus' Blunders

Concerning the psyche of Crassus' troops, they, like many Romans, were highly superstitious. For the Romans, before seminal events - appointment to offices, engagements in war - sacrifices and the 'reading' of animal intestines to predict the favorability of outcome was practiced. Augury, the study and meaning of bird behavior, was also performed. Coincidental to Crassus' unauthorized decision to invade Parthia, Cassius Dio says: "Many portents occurred in Rome: owls and wolves were seen, prowling dogs did damage, some sacred statues exuded sweat and others were destroyed by lightning. The offices, chiefly by birds and omens were with difficulty filled."(40.17) Moreover, the effect of words on destiny, especially in a curse, was also considered to have real effect.

Though it appears Rome's long-term plan was to take over the silk routes of Mesopotamia - as it blocked access to the Mediterranean by taking Syria and controlling the silk routes through Arabia - Crassus' particular decision on Parthia was at the time unpopular, and as Appian points out, considered inauspicious. To wage an unprovoked war on a nation they were at treaty with, was met with extreme disfavor by the tribunes. (Civil Wars, 2.3.18) In fact, the city was in an uproar as Crassus had to be safely escorted out of town by Pompey. Ateius, the tribune, was so upset that he announced a rare curse on Crassus at the city's gates. The effects of the curse and inauspiciousness of Crassus' decision were thought to have been the cause of other bad omens as well. But his many blunders did not help either. After his exit from Rome, he went to Brundisium, a favorite port for departure to the east. There Crassus would commit his second false start. Because of the terrific storms in the Mediterranean during the winter months, maritime traffic in ancient times came to a standstill. It was still winter, but Crassus decided to go anyway. With approximately 1,000 nautical miles to get to Syria, he lost many of his vessels carrying troops and supplies.

After landing at Galatia just north of Syria, then crossing the Euphrates and taking and garrisoning some of Parthia's westernmost less loyal cities, he crossed back over to Syria to wait for his son, Publius, who was coming from Caesar's war in Gaul. Crassus' plan was to follow the Euphrates east, as supplies were conveyed on it, and proceed toward Seleucia. But Artavasdes II (r. 55-34 BCE), king of Armenia and ally of Rome, had different advice. He knew the terrain and the Parthians. The Parthians, with their horses, warred best in the open areas of Mesopotamia. He suggested the Romans go by way of Armenia and attack from the mountains, as the king would help and provision them on their way. Regardless, Artavasdes promised troops to help fight the Parthians. Though Mark Antony (83-30 BCE) would later try the mountain route in 36 BCE, Crassus stuck to his plan - which might have worked, except for a spy sent by Surena. Once an ally of Pompey, Ariamnes, an Arab chief, also knew the capabilities of the Parthians and switched allegiance. Gaining Crassus' confidence, he claimed he knew where the Parthians were, and they were few in number; but the Romans needed to hurry as they were gathering their belongings to flee to Scythia; besides this, their king was nowhere to be seen (Orodes was in fact attacking Artavasdes). Keeping Surena informed, Ariamnes led the Romans into the desert waste, then disappeared. It was a trap! Thirsty and exhausted, the Romans finally came to a spring when they discovered the Parthians were indeed close by. Cassius (c. 86-42 BCE), Crassus' senior lieutenant, suggested they rest at the spring overnight to refresh and attack in the morning, but Publius wanted to go now, and Crassus agreed. Yet Cassius' advice would have been best. Not only were the troops physically taxed, but several things happened along the way that made them unnerved as well.

Circumstances, Statements & 'Signs'

After Crassus' initial token of success in western Mesopotamia, then joining with his son, who brought a thousand handpicked cavalry, he lost crucial time levying taxes and plundering the temple in Syria. That allowed the Parthians time to accrue strength and solidify plans. As a bad portent, on leaving the temple of the Syrian nature-goddess Atargatis at Hieropolis, Publius stumbled and fell at its gate as Crassus fell over him. Then, as Crassus' men were led at first to believe their confrontation with the Parthians would be a cakewalk, those escaping Parthia's retaking of their western cities brought stories of horse archers shooting armor-piercing arrows and of their unstoppable horse tanks, the Parthian cataphracts. "When the soldiers heard this, their courage ebbed away." Even some of Crassus' officers, Cassius as well, thought the whole expedition should be reconsidered. On top of this, the seers let it be known all the signs from their sacrifices were "bad and inauspicious" (Plutarch 18.2-5). Nevertheless, Crassus was having none of it.

On crossing back over the Euphrates to invade Parthia, several more bad occurrences and ‘signs' happened. First, great peals of thunder and lightning, with torrential rain and hurricane-like wind, hit the group. Next, one of Crassus' finest horses, richly caparisoned, dragged its handler under the waves. Then, two lightning bolts struck the area where the troops were to encamp. Then at mealtime, lentils and salt were served first. That was considered a bad omen because lentils and salt were "tokens of mourning and offerings to the dead" (19.5). Exasperated, Crassus harangued his men for their timidity and superstition. Not helping things, he angrily said he ought to destroy the bridge they had just crossed because not one of them was going to return! Taken by his men to mean they were all going to die, Plutarch says Crassus should have rephrased what he really meant - that destroying the bridge might keep them from retreating - but did not. Moreover, when Crassus was handed the viscera after the customary sacrifice was performed, he dropped it to the ground. Then, after seeing his men were "beyond measure distressed," he smiled, saying flippantly, "Such is old age, but no weapon, you may be sure, shall fall from its hands" (19.6). Finally, after receiving word that aid from Artavasdes was not coming because he was under attack by Orodes; on the day of battle, as they were ready to move out, Crassus came out of his tent wearing a black robe instead of the customary purple one. Then, after quickly changing, it happened the standard bearers were able, only after great exertion, to extract the eagle standards from the ground. Knowing these incidents would be construed as more bad omens, he made light of them. Nonetheless, when Crassus finally saw but few scouts straggling back with reports the others were killed and the enemy was gathering in great numbers, he realized he had been deceived. The Parthians were not fleeing; neither were they few in number; neither was their king AWOL! Finally, after all his cavalier statements and actions, Crassus, according to Plutarch, was beside himself. And Surena, no doubt, would pile on.

The Battle

As the two sides closed ranks, Surena hid the bulk of his force behind his advance guard so his army would appear small. Then, "to confound the soul and unseat judgment," the Parthians filled the plain with a deafening beat of kettledrums. Plutarch describes their sound as "like the bellowing of beasts mixed with sounds resembling thunder" (23:7). Then, prior to the Romans' advance, Surena had his cavalry cover their armor with skins and robes. After the Romans came closer, the Parthians spread out, uncovered their armor, and were suddenly seen by the Romans "blazing in helmets and breastplate; their Margianian steel glittering keen and bright" (24.1). These psychological tactics could only have added disquiet to the legionaries' already frazzled nerves.

When it came to the battle itself, the Parthians would show how their light and heavy horse worked flexibly and in concert. Though Surena thought at first to send his cataphracts to break the Roman lines, when he saw the depth of the Roman formation, with shields interlocked, he decided on missile bombardment. Surrounding the Romans, the Parthian horse archers released an unmerciful barrage of arrows that tore through armor. Thinking the Parthians might run out of ammunition when Crassus saw Parthian camels coming with a fresh supply of arrows, he sent his son, Publius, at the head of the cavalry to attack. The Parthian light horse then feigned retreat and after a long chase, ran the Romans into an ambush of cataphracts. As the Romans halted, the Parthian light horse circled about and kicked up such a thick cloud of dust the Romans tightened their formation and were again easy targets. Finally, Publius charged the cataphracts, but the cataphracts, with their superior horses, armor, longer lances, and probably more skilled riders, soon prevailed. That day the Romans suffered their worst defeat: Publius died in battle; Crassus would later be executed; few Romans would escape, and worst of all, their standards were taken.

Conclusion

While Crassus was an accomplished politician and wealthy businessman with prior martial success, his defeat at the hands of the Parthians was a result not only of his tactical blunders and verbal missteps but occurrences beyond his control that were viewed as ominous by his troops who were physically and mentally taxed before battle. Adding to this, Parthia's warfare of subliminal messaging and diversion by Orodes, misinformation by a spy, Surena's display of aggression, and feigned movements on the battlefield - all contributed to Rome's defeat at Carrhae. But perhaps the most significant psychological blow for the Romans was Surena's capture of their standards, which certainly would have been displayed as trophies. Using the pretext of retaking the standards, Mark Antony would come at the Parthians again in 36 BCE by the route the king of Armenia suggested to Crassus - from the mountains to the north - but he too would be defeated in retreat. These two setbacks caused Rome to sue for peace in 20 BCE as Augustus was also able to negotiate, and Rome could breathe a sigh of relief, the return of her standards. This peace between the two sides would last for over a hundred years (until Trajan came at Parthia again in 115 CE) and was a direct result of Surena's brilliant campaign against Crassus of Rome in 53 BCE.