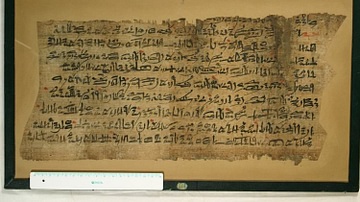

A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe is a Sumerian composition relating a dialogue between an elder scribe and a young graduate from his school. The piece is dated to the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) and, although originally interpreted as an accurate depiction of the life of a scribe, might also be understood as satire.

Scholar Jeremy Black (among others) has pointed out that students used to copy this piece as part of their exercises and it is possible, even likely, considering this work was part of the curriculum for older students, that it was intended as a light-hearted parody of a teacher's lecture. The teacher in the piece speaks condescendingly to the new graduate, emphasizing what a great teacher he had in the past, how he honored that legacy, and how the student should do the same for him, but then, instead of the student accepting the lesson in humility, he responds by listing all he has done for his teacher already, what he continues to do, and how he needs no more lectures.

The piece would have been copied toward the end of the twelve years of instruction required to become a scribe and may have indeed been a form of satire or, perhaps, a work copied and recited in honor of one's teacher before graduation. Although the details of the teacher's lecture and the student's response may be exaggerated for comic effect, the piece is still thought to describe the teacher-student relationship and the responsibilities of a scribe in ancient Mesopotamia upon graduating.

Writing & Schools

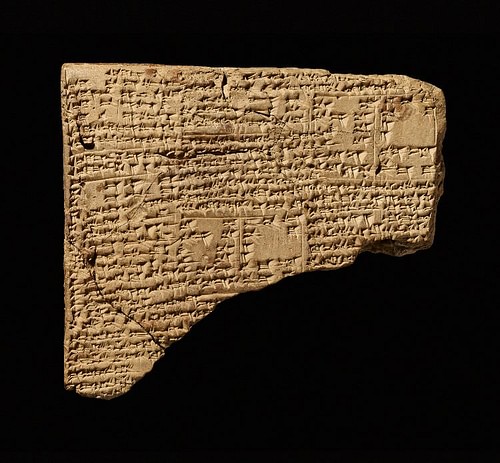

Writing was invented by the Sumerians c. 3500 BCE, and by c. 3200 BCE, had evolved from pictographs to phonograms (symbols representing sound) in the city of Uruk. This writing system, cuneiform, was practiced with a stylus (a reed with a sharpened end) on clay tablets and is thought to have developed in response to a need for long-distance communication in trade. Black writes:

For centuries after the first appearance of writing in southern Iraq in the late fourth millennium BCE, it served an exclusively administrative function. Cuneiform was a mnemonic device designed to aid accountants and bureaucrats, rather than a vehicle for high art. (xlix)

By the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE), phonograms were in use, and one could express more complex thoughts than how many jugs of beer or carts of grain had been sent to or from a given city. Nisaba, formerly a grain goddess, had evolved by this time into the goddess of writing and accounts and her priests understood that, in order for this craft to be preserved, there had to be schools. The Sumerian scribal school (the edubba) developed during this era, teaching writing, reading, history, religion, and mathematics. These schools were firmly established by the Early Dynastic Period and spread throughout Sumer.

Sumerian Education & Schools

The curriculum of the edubba ("House of Tablets") progressed from simple instruction in how to use a stylus and clay tablet to writing signs, symbols, letters, and then words and sentences while also learning what to write about. The word cuneiform comes from the Latin cuneus for wedge and refers to the wedge-shaped style of writing produced by a stylus on a piece of moist clay. One needed to know how to handle the clay tablet and the stylus properly before one could actually write anything, and this instruction began when one entered the edubba at around eight years old.

The process was not as simple as merely pressing the stylus into the clay. One held the tablet in one hand and turned it while making the specific marks with the stylus which could be compared to texting today if one had to continually turn one's device in one hand while making the signs, instead of pressing letters, with the other. Students were therefore taught first how to make the vertical, horizontal, and oblique wedge clearly and exercise tablets unearthed in the modern era show that they practiced this repeatedly until it was mastered.

The majority of the students were boys from upper-class families of the nobility, clergy, and merchant class who had the kind of income to afford education and were not required for agricultural or industrial work. Girls, also from wealthier families, could attend the edubba if they were studying to be priestesses, doctors, or were the daughters of nobility, though there are clear examples of literate women who were merchants, but, overall, girls were a minority. After mastering the basics of cuneiform writing, students would progress to learning and memorizing its 600 characters.

Moving from the elementary to the second stage, students were taught how to use these characters to form words and then sentences. Exercise tablets give evidence of students making lists of people, places, and things – nouns – repeatedly before advancing on to the third stage of writing grammatically correct sentences and learning mathematical principles, accounting, and literature. Black comments:

The scribal schools were undoubtedly training the next generation in Sumerian literacy. But to learn literature is to learn more than literacy. The students were being inculcated with the values of their society and the values of the profession in which they were to serve. (xliii)

To instill these values and maintain discipline, students were beaten if they failed to perform as expected or broke the rules of the edubba. A student could be beaten for failure to produce an assignment, speaking back to a teacher, speaking in class without permission, absenteeism, leaving the school early without permission, inappropriate dress, sloppy work, or any other infraction of the rules set by the teacher (supervisor) of the school.

Schools seem to have begun in private homes, and the rules were dictated by the individual homeowner. In time, separate buildings were designated as schools, but it seems the supervisor of each individual school still made the rules. The discovery of exercise tablets in the ruins of buildings identified as homes led to the understanding that Sumerian children were home-schooled or that all schools operated out of homes, but a more likely explanation for these finds is that students brought home their school tablets to recite to their parents as an aspect of homework assignments or to practice their skills.

These tablets might have been discarded in the home or kept there and reused in the same way they were at school. Black notes, "as the recycling bins in [scribal schools] hint, tablets were not meant to be kept unless there was a good economic need for them: to prove ownership or rights" (xlvii). The exercises found written on the tablets in homes were almost certainly not the ones that first appeared on them. Schools regularly collected the clay tablets, soaked them in bins of water to soften them, and then reused them. The assignments that have survived for over 2,000 years would have been tablets that had been overused and discarded as a whole at one time or individually.

Having mastered reading, writing, math, and history, as well as being informed in their religion, values, and culture, the last stage of a student's education was the study of literature, which included the elementary texts of the Tetrad (groups of four compositions) and the Decad (groups of ten compositions). The Tetrad was comprised of works using simple words and expressing single themes such as the Hymn to Nisaba while the works that made up the Decad were more complex compositions in form, theme, and overall meaning. Following the Decad, were even more intricately crafted texts such as The Curse of Agade and, among these, was A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe, also known in the modern era by its catalog title of Edubba C.

The Text

The first part of the text (lines 1-28) gives the lecture of the teacher who begins by telling the new graduate how greatly he honored his own teacher and how worthy a student he had been, before passing on the advice that his teacher had given to him. Based on the protocol of the edubba, the student would have been expected to receive the lecture in silence and answer with some humble words of gratitude, but the graduate responds by essentially telling the teacher he does not need to hear any of this (lines 29-53). The teacher accepts the rebuke and gives the graduate his blessings (lines 54-55), the graduate accepts and thanks the teacher (lines 56-59), the teacher then extends his blessings (lines 62-72), and the piece ends with the traditional conclusion of a composition by praising Nisaba (lines 73-74). Ellipses throughout indicate words or lines missing from the text.

The following passage is taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al.

1-2: (The supervisor speaks:) "One-time member of the school, come here to me, and let me explain to you what my teacher revealed."

3-8: "Like you, I was once a youth and had a mentor. The teacher assigned a task to me – it was man's work. Like a springing reed, I leapt up and put myself to work. I did not depart from my teacher's instructions, and I did not start doing things on my own initiative. My mentor was delighted with my work on the assignment. He rejoiced that I was humble before him, and he spoke in my favour."

9-15: "I just did whatever he outlined for me – everything was always in its place. Only a fool would have deviated from his instructions. He guided my hand on the clay and kept me on the right path. He made me eloquent with words and gave me advice. He focused my eyes on the rules which guide a man with a task: zeal is proper for a task, time-wasting is taboo; anyone who wastes time on his task is neglecting his task."

16-20: "He did not vaunt his knowledge: his words were modest. If he had vaunted his knowledge, people would have frowned. Do not waste time, do not rest at night – get on with that work! Do not reject the pleasurable company of a mentor or his assistant: once you have come into contact with such great brains, you will make your own words more worthy."

21-26: "And another thing: you will never return to your blinkered vision; that would be greatly to demean due deference, the decency of mankind. Worthy plants calm the heart, and sins are absolved. An empty-handed man's gifts are respected as such. Even a poor man clutches a kid to his chest as he kneels. You should defer to the powers that be and … that will calm you."

27-28: "There, I have recited to you what my teacher revealed, and you will not neglect it. You should pay attention – taking it to heart will be to your benefit!"

29-35: The learned scribe humbly answered his supervisor: "I shall give you a response to what you have just recited like a magic spell, and a rebuttal to your charming ditty delivered in a bellow. Do not make me out to be an ignoramus – I will answer you once and for all! You opened my eyes like a puppy's, and you made me into a human being. But why do you go on outlining rules for me as if I were a shirker? Anyone hearing your words would feel insulted!"

36-41: "Whatever you revealed of the scribal art has been repaid to you. You put me in charge of your household and I have never served you by shirking. I have assigned duties to the slave girls, slaves, and subordinates in your household. I have kept them happy with rations, clothing, and oil rations, and I have assigned the order of their duties to them, so that you do not have to follow the slaves around in the house of their master. I do this as soon as I wake up, and I chivvy them around like sheep."

42-49: "When you have ordered offerings to be prepared, I have performed them for you on the appropriate days. I have made the sheep and banquets attractive, so that your god is overjoyed. When the boat of your god arrives, people should greet it with respect. When you have ordered me to the edge of the fields, I have made the men work there. It is challenging work which permits no sleep either at night or in the heat of day, if the cultivators are to do their best at the field-borders. I have restored quality to your fields, so people admire you. Whatever your task for the oxen, I have exceeded it and have fully completed their loads for you."

50-53: "Since my childhood you have scrutinised me and kept an eye on my behaviour, inspecting it like fine silver – there is no limit to it! Without speaking grandly – as is your shortcoming – I serve before you. But those who undervalue themselves are ignored by you – know that I want to make this clear to you."

54-55: (The supervisor answers:) "Raise your head now, you who were formerly a youth. You can turn your hand against any man, so act as is befitting."

56-59: (The scribe speaks:) "Through you who offered prayers and so blessed me, who instilled instruction into my body as if I were consuming milk and butter, who showed his service to have been unceasing, I have experienced success and suffered no evil."

60-72: (The supervisor answers:) "The teachers, those learned men, should value you highly. You who as a youth sat at my words have pleased my heart. Nisaba has placed in your hand the honour of being a teacher. For her, the fate determined for you will be changed and so you will be generously blessed May she bless you with a joyous heart and free you from all despondency…at whatever is in the school, the place of learning. The majesty of Nisaba …silence. For your sweet songs even the cowherds will strive gloriously. For your sweet songs I too shall strive and shall …They should recognise that you are a practitioner (?) of wisdom. The little fellows should enjoy like beer the sweetness of decorous words: experts bring light to dark places, they bring it to closes and streets."

73-74: Praise Nisaba who has brought order to…and fixed districts in their boundaries, the lady whose divine powers are divine powers that have no rival!

Conclusion

On the surface, the piece seems to be a complimentary text a Sumerian graduate would have copied and, perhaps, recited to his teacher, and this may be exactly the purpose the work served. Jeremy Black, however, suggests a different interpretation:

Such compositions have often been used as primary evidence for the working conditions and professional attitudes of Old Babylonian scribes. But the archaeological evidence from scribal schools shows that this work and others like it were copied by the trainee scribes in the process of their education…this means we need to think quite carefully about how the students themselves interpreted them. Did they recognize in these dialogues a true picture of school life, or some humorous heightened reality which bore only tangential similarity to their own experiences and feelings? (277)

Black notes several instances of humor and sarcasm in the student's response beginning with "your charming ditty delivered in a bellow" (lines 30-31) and continuing on through. These gibes at the teacher (such as "without speaking grandly – as is your shortcoming", lines 51-52) suggest the work was intended as satire and is more of a reflection of how the author, who would have almost certainly been a teacher, imagined a student would like to respond to a superior than a record of any actual conversation. At the same time, however, the respect the teacher and his former student show each other is understood as an accurate representation of that kind of relationship in the scribal schools of ancient Sumer.