During the 21st century BCE, an era known as the Ur III period in Mesopotamia, many records of court hearings were drawn up in Umma, a city in what is now southern Iraq. One court record relates a dispute between two women. The name of one of the women is unknown, she was described in the text only as the wife of a man named Ur-lugal. The other woman was named Geme-Suen. Court cases like theirs give us a vivid sense of how the Mesopotamian judicial system worked.

Geme-Suen's Case

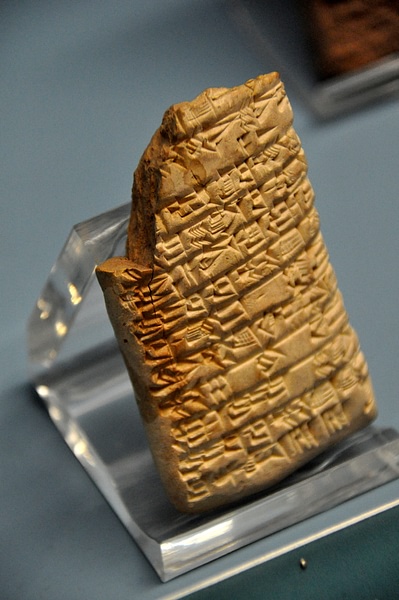

In the Ur III period, many court records were drawn up in the city of Umma. We do not know exactly where this court proceeding took place, but it was probably close to a temple. A scribe kept track of what happened, and it is his record that is to be found in the British Museum on a tablet that is just a little more than two inches wide and three inches tall. The discussion began with Geme-Suen stating that the wife of Ur-lugal had borrowed two minas of silver from her, and that she still owed some of the money. Two minas represented a large amount of wealth, even for a relatively rich person. One shekel of silver was equivalent to 300 liters of barley, and a manual worker was paid 60 liters of barley per month; therefore a shekel of silver represented five months of pay. 60 shekels made a mina, so the two minas that Ur-lugal's wife had borrowed were equivalent to 120 shekels, or 50 years' pay for a worker. It is unclear what Ur-lugal's wife needed it for, but Geme-Suen must have been a wealthy woman to have had that amount on hand and available to lend. Ur-lugal was described as the head-gardener, so his wife would not have been poor either.

It is possible that a contract had been drawn up at the time that Geme-Suen had lent the silver to Ur-lugal's wife. Contracts were widely used by this time to create formal records of such things as loans or sales. It would have been written by a scribe, in the presence of witnesses, and the interest rate might have been listed. Usually, for loans of silver, this was steep – 20 percent. Some loan contracts also listed a time when the loan had to be repaid.

Back in the court room, the wife of Ur-lugal had an answer to Geme-Suen's demand for the rest of the loan to be repaid. "Ki'ag closed my case," she stated, presumably speaking to the judge who was presiding (Molina, 202). She meant that this case had already been tried and decided in her favor. She did not owe anything. The man named Ki'ag, who had overseen the previous trial, seems to have been present for this new one as well. He was one of three known judges at Umma who presided in court cases, so he would have been well known to the judge to whom the wife of Ur-lugal was speaking. We know from other sources that Ki'ag had also donated animals for sacrifice at the city's New Year's festival, and on one occasion he had administered an oath to someone in his own house. He was an eminent man of Umma.

The wife of Ur-lugal continued to speak in her own defense, by identifying another powerful man who would support her claim: "Lu-Suen was my commissioner in the concluded case," she said (Molina, 202). Commissioners, with the title mashkim, oversaw court cases in the Ur III period. They prepared everything in advance of the trial, recorded the outcome, and are mentioned frequently in the documents. In this instance, the judge decided to check her story. He called on Lu-Suen to confirm that the wife of Ur-lugal was telling the truth, but it turned out that she had made a mistake in mentioning him. Lu-Suen did not help her. The record states that "he declared: 'It is a lie'" (Molina, 202).

What seems to have happened next is that, interestingly, Ki'ag, the judge from the first case, got involved. He asked all five of Ur-lugal's children to swear an oath, presumably to confirm that their mother had been telling the truth. But they decided not to support her and refused to swear. Had they agreed, they would all have been required to go to the temple so that the oath could be taken in the presence of the god. At this point, Ur-lugal's wife decided to back down. Neither the commissioner from the previous trial nor her own children were willing to lie for her. She acknowledged that, yes, she still owed ten shekels of silver to Geme-Suen. Not only that, but one of her sons admitted that he also owed five shekels.

The court case does not say anything else, except to list five witnesses who attended the court proceeding. Records like this almost always ended with the oath, whether or not the people involved decided to swear it because the oath (or refusal to swear it) often determined the judge's decision. In this case, Geme-Suen won the lawsuit, and the wife of Ur-lugal had to pay back the rest of the silver.

Legal System in Mesopotamia

This little slice of life in Umma reflects several aspects of the legal system there, which are confirmed by other court cases as well. First, unlike in most other Mesopotamian cities and other times, each case in Umma was tried by one judge. Elsewhere, a whole panel of judges – as many as seven of them – was needed. No one at this time was a judge by profession; men like Ki'ag who took on the role from time to time were literate and important in the city, but they had other jobs as well. Second, the judge cared about evidence and wanted to make sure that the parties to the case were telling the truth. That was why he questioned Lu-Suen, and that was what the oath would have been for – judge Ki'ag tried to get Ur-lugal's children to swear in support of their mother so that he could determine whether she was being truthful.

The original statements in a trial were rarely made under oath, but oaths often came in later in the proceedings and were seen as potent legal tools throughout ancient Near Eastern history. Oaths brought the power of the gods into the lawsuit. They are mentioned in Ur-Namma's laws as well. One law states that "if a man appears as a witness, but retracts (his) oath, he will make compensation for whatever was the matter in that trial" (Ur-Namma's Law, 38). The children of Ur-lugal had not presented themselves as witnesses – they had been called up by the judge – and they were wise not to take that oath. Apparently, they refused because their mother was lying and they knew they would have perjured themselves. It would not have been worth it: they could have been responsible for the silver due in the case. Another nagging concern no doubt prevented them from lying under oath: the gods would have known they had done so, and the gods had no patience with humans who swore false oaths in their names. The children would have believed that the gods' punishment was likely to have been much worse than paying an amount of silver. So, refusing to take an oath was a way of telling the judge that you would be lying if you did so. This helped him determine the truth of the case.

In the case of Geme-Suen v. Ur-lugal's wife, the judge decided in favor of the richer, more powerful of the two women, but this was not a result of the judicial system favoring the rich. The court records reflect surprising transparency in the legal system, and a genuine desire for justice to prevail. Had Geme-Suen been at fault, it is clear from other cases that she would have been the one who would have had to pay. It is also clear, not just from the laws but also from records of court cases, that fines were by far the most common form of punishment.