The fall of Maximilien Robespierre, or the Coup of 9 Thermidor, was a series of events that resulted in the arrests and executions of Robespierre and his allies on 27-28 July 1794. It signaled the end of the Reign of Terror, the end of Jacobin dominance of the French Revolution (1789-1799), and the beginning of the Thermidorian Reaction.

Since September 1793, Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety had overseen the bloodletting of the Terror, during which hundreds of thousands of French citizens were arrested under suspicion of counter-revolutionary activity; 16,594 of these 'suspects' were executed by guillotine, while tens of thousands more were killed in massacres or died in prison while awaiting trial. The Terror had been implemented to guide the French Republic through a particularly turbulent time. But once the danger had passed, Robespierre refused to give up power, insisting that internal enemies still presented a threat. Some members of the National Convention, fearing they had been marked out for execution, preemptively denounced Robespierre, declaring him to be an outlaw on 27 July 1794.

The Robespierrists took refuge in the Hôtel de Ville, sparking a brief standoff between the Paris Commune and the National Convention. But the Commune's power had diminished during the Terror, allowing Convention troops to swarm the Hôtel, taking Robespierre, Louis Antoine Saint-Just, Georges Couthon, and others into custody. The next day, 21 leading Robespierrists were guillotined without trial in Paris. In the following months, other Jacobin leaders across France were arrested and executed for their own roles in the Terror.

Beneath the Shadow of Terror

5 September 1793 had found the infant French Republic in grave danger. On the frontiers, the armies of despotic Europe encroached further onto French soil, while domestically, several key cities had rebelled against the revolutionary government in the federalist revolts. Inflation was rampant, and unemployment endemic; such was believed to be the work of counter-revolutionary conspirators who worked tirelessly to undermine the Revolution and return France to a state of oppression. Feeling the noose begin to tighten, mobs of Parisians had invaded the National Convention, France's provisional legislature, on 5 September, demanding affordable bread and that their enemies be unmasked and brought to justice.

This was the spark that lit the Terror. The National Convention responded to their demands by heaping executive power onto a twelve-man assembly known as the Committee of Public Safety, which was tasked with defending the Republic and unmasking domestic traitors. To give the Committee its necessary authority, the National Convention agreed to suspend the new Republican Constitution of 1793 and went to work overseeing the arrests and executions of thousands of counter-revolutionary suspects. It reformed the military, leading to major victories by French armies in the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797) at the Battle of Wattignies and the Siege of Toulon. By the end of 1793, the federalist revolts had been crushed, the foreign invasions stymied, and supposed counter-revolutionary agents imprisoned or executed. France had paid dearly for this new security with blood, and many hoped that the Terror could now be ended and that the dormant constitution would now be implemented.

Yet the Committee of Public Safety was not about to give up its executive powers. Maximilien Robespierre, whose position as the dominant figure on the Committee made him the effective ruler of France, was convinced that there were still counter-revolutionaries who needed to be unmasked. Once a small-town lawyer from Arras, Robespierre had risen to prominence in the revolutionary Jacobin Club thanks to his unyielding quest for a virtuous republic, one in which citizens put the greater good above their own selfish desires. A pupil of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Robespierre believed fervently that the only way to reach a just and equal republic was by rooting out the corruption and tyranny present within that society. His refusal to compromise on these beliefs simultaneously made him well-loved by his supporters and regarded as merciless by his enemies; he self-righteously equated his principles with those of the Revolution itself, so that disagreeing with him was tantamount to disagreeing with the Revolution. To Robespierre's mind, this was indistinguishable from treason.

Whether Robespierre was as well-intentioned or simply power-hungry, the fact remains that he consolidated his power in the spring of 1794, sending enemies to both his political left and right to the guillotine. These power struggles in the Reign of Terror saw the executions of Georges Danton and Camille Desmoulins, two revolutionary leaders who had formerly been close friends and allies of Robespierre's but had become his enemies when they advocated for scaling back or even ending the Terror. Robespierre's willingness to sacrifice his friends for his principles proved that he would stop at nothing to achieve his goals, causing many other revolutionary leaders to wonder if they would be next.

Masters of France

And indeed, by June 1794 it appeared that many of them were right to worry. On 8 June (or 20 Prairial in the French Republican calendar), the Jacobins held a massive festival on the Champ de Mars to celebrate the new Cult of the Supreme Being, a deist religion completely devised and implemented by Robespierre. Dressed ostentatiously in a sky-blue coat, golden trousers, and a tri-colored sash, Robespierre took on the role of the high priest of this strange new cult, delivering self-indulgent speeches from atop a massive, artificial mountain. By some accounts, half a million people attended this festival, marking the peak of Robespierre's popularity. Many deputies of the Convention were disturbed by this development, seeing it as Robespierre's attempt to solidify himself as dictator. Jacques-Alexis Thuriot, who had been a friend of the executed Danton, muttered to a companion, "Look at the bugger. It's not enough for him to be master, he has to be God" (Doyle, 278).

Just two days after the Festival of the Supreme Being, Robespierre introduced the infamous Law of 22 Prairial to the National Convention. Penned by Georges Couthon, a Robespierrist on the Committee of Public Safety, the law was drafted in response to two assassination attempts on Robespierre and fellow Committee member Collot d'Herbois back in May. Effectively, the law intensified the Terror by accelerating trials and increasing the likelihood of a guilty verdict, which now necessarily meant death. Between the implementation of this law on 10 June and 27 July, 1,400 people were guillotined in Paris alone.

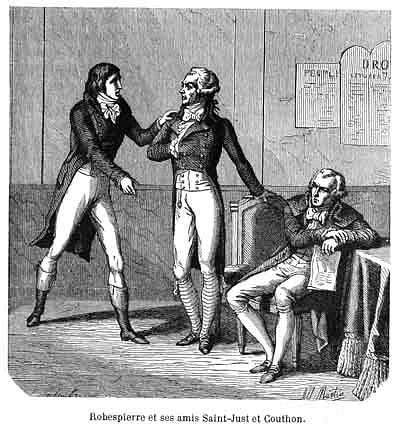

Meanwhile, Robespierre continued to cement his power. He had long controlled the massively influential Jacobin Club, and now dominated the powerful Committee of Public Safety as well. Within the Committee, Robespierre formed an unofficial triumvirate with his supporters Couthon and Louis Antoine Saint-Just; the three of them had devised the Law of 22 Prairial and now reigned as the true masters of France. Of course, they could not hold onto power without their allies in the Paris Commune. The city government was controlled by Robespierre's friend Claude Payan while Fouquier-Tinville, the dreaded chief prosecutor of the Revolutionary Tribunal, was known to take marching orders from Robespierre. The National Guard was commanded by François Hanriot, a foul-mouthed sans-culotte who had helped bring the Jacobins to power by causing the fall of the Girondins the year before. By July 1794, Robespierre and his supporters appeared to be on their way to permanent dictatorship; if they were not stopped, France would sink further into the depths of Terror.

Conspirators Gather

One does not become the virtual dictator of a regime of Terror without making enemies. And one as self-righteous as Robespierre had certainly made more than a few. Joseph Fouché, a representative-on-mission, had been recalled to the capital by Robespierre due to his atheistic policies and his particularly brutal repression of the Revolt of Lyon. Paul Barras, who had been overseeing the Siege of Toulon, was similarly recalled after being accused of enriching himself in the aftermath of the siege. Jean-Lambert Tallien felt slighted when Robespierre ordered the arrest of his 21-year-old mistress. Marc-Guillaume Vadier, a leading member of the Committee of General Security who had played a large role in the Terror himself, was turned against Robespierre when the latter stripped him of much of his authority over policing. All of these men had reason to believe they were next on Robespierre's list of traitors.

Feeling backed into a corner, these men, later known as the Thermidorians, were made much more dangerous by the fact that their lives were on the line. They were inadvertently aided by Robespierre himself, who retreated from public life on 18 June and seldom reappeared until 26 July. The reason for this withdrawal is unknown; it has been speculated that his health was failing, as he had become visibly frailer since his rise to power ten months before. Others have argued that he was fatigued, or that the executions of Danton and Desmoulins still weighed heavily on his conscience.

Whichever case, his absence allowed his enemies time to gather and plan their attack. They spoke openly on the Convention floor about Robespierre's tyranny, referring to him as a "murderer" and denouncing his self-centered behavior at the Festival of the Supreme Being. They were aided in their argument by the realities of the Terror, which was still escalating; in the month of Messidor, an average of 26 people were being executed every day. In the words of Fouquier-Tinville himself, "heads were falling like slates off the roof" (Davidson, 222). While not all of Robespierre's enemies necessarily wanted to end the Terror, much of France had become tired of the bloodshed, a fact that played into the hands of the conspirators.

Robespierre Returns

On 8 Thermidor (26 July), Robespierre emerged from his seclusion to defend himself from political attack. He gave a two-hour speech before the National Convention, which he began with the grandiose statement:

The French Revolution is the first to have been founded on the theory of the rights of humanity and justice. Other revolutions have required nothing but ambition; ours imposes virtue. (Scurr, 344).

But what started as an inoffensive tribute to the Revolution slowly transformed into a warning of a vast counter-revolutionary conspiracy meant to topple the Republic. He defended himself against charges of dictatorial aspirations, wondering who could truly believe that he wished to see the Convention "cut its own throat with its own hands" (Scurr, 345). The true "monsters," he declared, were masquerading as devoted patriots, hiding in both the Convention and the Committee of Public Safety. He claimed to possess a list of traitors, who would soon be unmasked and brought to justice. He named no names except, curiously, for Pierre Cambon, head of the Finance Committee, content to let the rest of the deputies wonder which among them were traitors.

At first, the speech appeared to be warmly received. Georges Couthon proposed a vote on whether it should be printed and distributed to the provinces, as was usual with Convention speeches. The Convention seemed ready to blindly follow along with protocol, until Cambon meekly stood, probably realizing that if he did not speak now he would surely be carted off to the guillotine. With nothing to lose, Cambon declared that "it is time to tell the whole truth: one man is paralyzing the National Convention; that man is the one who has just made a speech; it is Robespierre!" (Scurr, 349).

Cambon was shouted down by Robespierre's allies, but it was too late; like a flood bursting from a cracked dam, deputies stood and called for Robespierre to name the names of those he accused. Robespierre refused. Now in an uproar, the Convention voted against publishing Robespierre's speech. That evening, a defiant Robespierre read his speech again at the Jacobin Club, where it was met with rapturous applause; Collot d'Herbois and Billaud-Varenne, two of Robespierre's rivals on the Committee of Public Safety, were chased from the club by frenzied Jacobins, who were shouting "to the guillotine!" Robespierre concluded his speech with his usual promise that he would gladly give his life for the good of the fatherland. He had no idea just how soon that promise would come to fruition.

Thermidor

Just four years earlier, Louis Antoine Saint-Just had been an unknown boy who excitedly wrote a fan letter to his idol, Robespierre. Now, at just 26, he was one of the most powerful men in France, whose position, and life, depended on how well he could defend the man he had once idolized. He had been up all night preparing the speech that he was now about to deliver before the National Convention, on the beautiful sunny morning of 27 July 1794. But he barely uttered his first sentence when he was shouted down by a cascade of voices.

Tallien accused him of giving an unapproved speech, while Billaud-Varenne recounted how he had been chased from the Jacobins the night before. Collot d'Herbois, who was fatefully serving as the Convention president that day, did nothing to stop the madness. At the tribune, Saint-Just froze, tongue-tied and unable to mount one of the fiery counterattacks he had become famous for. Robespierre jumped to Saint-Just's defense, at which point he was loudly booed and heckled by the gathered deputies, who shouted, "down with the tyrant!" Deputies laughed at Robespierre's desperate attempts to speak over the commotion, with one deputy shouting, "It is the blood of Danton that chokes him!" To this, Robespierre raised his voice enough to retort: "Danton! Is it Danton you regret? Cowards! Why did you not defend him?" (Scurr, 352).

Brandishing a dagger, Tallien demanded the arrest of Robespierre and his allies including Saint-Just, Couthon, Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas, and Hanriot, commander of the National Guard, the last of whom was not present. This motion was carried by a large majority. Robespierre's younger brother, Augustin, asked to be arrested alongside them; this was granted. Yet the arrests of the Robespierrists caused great anger from the Commune and the Jacobin Club, which threatened to revolt against the Convention. Hanriot ordered the Paris prisons to refuse to accept any prisoners being delivered by order of the National Convention. Subsequently, by nightfall, all five prisoners were free and hiding out in the Hôtel de Ville. It seemed the stage was set for a climactic battle between the Paris Commune and the National Convention.

Showdown

As it happened, the uprising promised by Hanriot and the Jacobins never came. Rather ironically, the power of the Commune and the Parisian sans-culottes had been greatly diminished by the Terror, as Paris' sections had been infiltrated by agents loyal to the Convention. Additionally, communication and troop movements were hampered by a sudden nighttime storm. As the sluggish insurrection struggled to organize itself, the Convention declared that the escaped Robespierrists were outlaws, thereby depriving them of their right to a trial. At 2 a.m. on 28 July, soldiers in the pay of Paul Barras entered the Hôtel de Ville, having snuck passed Hanriot's National Guardsmen by guessing the rather obvious password: "Vive Robespierre".

As the soldiers advanced up the stairs, Robespierre was in the middle of signing a decree officially calling the Commune to arms. When the soldiers burst into the room where the Robespierrists had gathered, chaos immediately ensued. Augustin Robespierre attempted to escape through a window, edging his way along a ledge until he slipped and landed on the street below; he was later picked up, half dead. The wheelchair-bound Couthon fell down a staircase, splitting his head open. Le Bas revealed two pistols, handed one to Robespierre, and used the other to commit suicide. Robespierre, having never handled a firearm in his life, perhaps tried to do the same; if so, the attempt was botched, and the bullet did nothing more than shatter his jaw. In another version of the story, Robespierre was shot by one of the trigger-happy gendarmes. Only Saint-Just remained still, stoically accepting his fate.

Execution

Between 2 and 3 in the morning, the wounded Robespierre was transported to the Committee of Public Safety, lying on a plank. Someone tied a white bandage around his jaw, which was bleeding profusely. Robespierre spent the last night of his life fading in and out of consciousness, in excruciating pain. At 9 a.m., Robespierre, Couthon, and Saint-Just were finally taken before the Revolutionary Tribunal; the mangled corpse of Le Bas and the dying Augustin Robespierre were also dragged in, as were Hanriot, Payen, and 16 other officials loyal to Robespierre. They were all condemned to die that day and were carted off to the guillotine. Robespierre sat in the tumbril, eyes closed, features obscured by his bandages. As they rolled through the streets to the scaffold, a woman was heard to shout: "Go now, evil one, go down into your grave loaded with the curses of the wives and mothers of France" (Scurr, 357).

Some of the condemned had to be carried up to the guillotine, but Robespierre ascended the steps unaided. He removed his bloodstained jacket before the executioner ripped the bandages off his face to give the guillotine's blade an unobstructed fall. Such an act caused Robespierre agonizing pain in his final moments; he let out a sharp, primal scream that was only silenced with the fall of the blade. The tenth of his group to be executed, Robespierre's death caused uproarious applause from the crowd that apparently lasted for 15 minutes. With him died the Terror and the dominance of the Jacobin ideology, which would be suppressed during the ensuing Thermidorian Reaction.