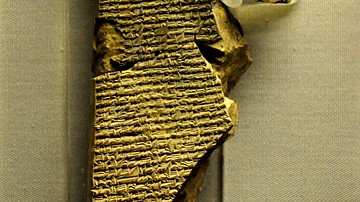

Inanna and Su-kale-tuda (c. 1800 BCE) is a Mesopotamian myth dealing with rape and justice in ancient Sumer. The work has been interpreted as an astral myth or a figurative account of the rise of the southern states against Akkad, but the most direct interpretation of the poem is a condemnation of the crime of rape.

The story centers on Inanna, the goddess of love, sex, and war, who, after traveling the heavens, comes to rest on earth in a garden under the shade of a tree. She falls asleep and is raped by the gardener Su-kale-tuda. Once Inanna awakes and realizes what has happened to her, she begins searching for her rapist, but, with his father's encouragement, he has hidden among "the black-headed people", the Sumerians, in the cities, to escape justice.

Enraged by the violation, Inanna sends three plagues upon the land to drive her rapist into the open: blood instead of water in the wells, storm winds, and flood, blocking off the highways used in trade. Finally, she appeals to the god Enki for justice who allows her to transform herself into a rainbow to search the world for Su-kale-tuda, who by this time is hiding in the mountains and trying to make himself as inconspicuous as possible.

She finds him, however, and decrees he must die for his crime. She tells him that his name will live on as her rapist forever, wherever songs are sung. In a society that valued memory as immortality, Su-kale-tuda is cursed to eternally be remembered as a rapist and coward. The poem is understood as having been transmitted orally until written down c. 1800 BCE and would have served as a cautionary tale regarding divine retribution for the crime of rape.

Summary & Commentary

The poem begins with Inanna as a young woman in the mountains intent on a mission "to detect falsehood and justice, to inspect the Land closely, to identify the criminal against the just" (lines 5-6). Lines 9-10 begin the refrain of "Now, what did one say to another? What further did one add to the other in detail?" which, according to scholar Jeremy Black, "creates an informal style evoking an orally transmitted story" (197) but, as the tale unfolds, also seems to ask an audience what they might do in the situation. What might one say to someone else regarding what they knew of a rape or the location of a rapist?

Lines 42-90 describe Enki, the god of wisdom and Lord of Eridu, teaching a raven the art of gardening, and succeeding, as the bird plants a leek which grows into the first date palm tree. The raven's skill as a gardener is then contrasted with the efforts of the youth Su-kale-tuda in lines 91-111, who cannot manage to make even one plant grow in his garden and is so inept he pulls up vegetables he has planted earlier.

A sudden dust storm blows up, temporarily blinding him, and when he clears his eyes, he sees Inanna descending to his garden to rest in the shade of a Euphrates poplar tree. The text makes clear that he knows he is seeing a goddess "who fully possesses the divine powers" (lines 101-102), but instead of honoring her, he waits until she falls asleep and then rapes her.

When dawn comes (when the sun god Utu-Shamash has risen), Inanna wakes and understands she has been violated. The rest of the poem deals with her pursuit of her rapist, the plagues she sends upon the land, and his eventual capture and condemnation.

The Text

The following passage comes from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al. Owing to considerations of space, only lines 112 (when Inanna is raped) to the conclusion (praising Inanna for her justice) are given. Ellipses indicate missing words or lines, while question marks suggest alternate translations for a word or phrase.

112-128: Once, after my lady had gone around the heavens, after she had gone around the earth, after Inanna had gone around the heavens, after she had gone around the earth, after she had gone around Elam and Subir, after she had gone around the intertwined horizon of heaven, the mistress became so tired that when she arrived there she lay down by its roots. Su-kale-tuda noticed her from beside his plot. Inanna ... the loincloth (?) of the seven divine powers over her genitals. ... the girdle of the seven divine powers over her genitals ... ... with the shepherd Ama-ucumgal-ana ... ... over her holy genitals ... Su-kale-tuda undid the loincloth (?) of seven divine powers and got her to lie down in her resting place. He had sex with her and kissed her there. After he had had sex with her and kissed her, he went back to beside his plot. When day had broken and Utu had risen, the woman inspected herself closely, holy Inanna inspected herself closely.

129-136: Then the woman was considering what should be destroyed because of her genitals; Inanna was considering what should be done because of her genitals. She filled the wells of the Land with blood, so it was blood that the irrigated orchards of the Land yielded, it was blood that the slave who went to collect firewood drank, it was blood that the slave girl who went out to draw water drew, and it was blood that the black-headed people drank. No one knew when this would end. She said: "I will search everywhere for the man who had sex with me". But nowhere in all the lands could she find the man who had had sex with her.

137-138: Now, what did one say to another? What further did one add to the other in detail?

139-140: The boy went home to his father and spoke to him; Su-kale-tuda went home to his father and spoke to him:

141-159: "My father, I was to water garden plots and build the installation for a well among the plants, but not a single plant remained there, not even one: I had pulled them out by their roots and destroyed them. Then what did the stormwind bring? It blew the dust of the mountains into my eyes. When I tried to wipe the corner of my eyes with my hand, I got some of it out, but was not able to get all of it out. I raised my eyes to the lower land and saw the high gods of the land where the sun rises. I raised my eyes to the highlands and saw the exalted gods of the land where the sun sets. I saw a solitary ghost. I recognised a solitary god by her appearance. I saw someone who possesses fully the divine powers. I was looking at someone whose destiny was decided by the gods. In that plot – had I not approached it five or ten times before? – there stood a single shady tree at that place. The shady tree was a Euphrates poplar with broad shade. Its shade was not diminished in the morning, and it did not change either at midday or in the evening."

160-167: "Once, after my lady had gone around the heavens, after she had gone around the earth, after Inanna had gone around the heavens, after she had gone around the earth, after she had gone around Elam and Subir, after she had gone around the intertwined horizon of heaven, the mistress became so tired that when she arrived there she lay down by its roots. I noticed her from beside my plot. I had sex with her and kissed her there. Then I went back to beside my plot."

168-176: "Then the woman was considering what should be destroyed because of her genitals; Inanna was considering what should be done because of her genitals. She filled the wells of the Land with blood, so it was blood that the irrigated orchards of the Land yielded, it was blood that the slave who went to collect firewood drank, it was blood that the slave girl who went out to draw water drew, and it was blood that the black-headed people drank. No one knew when this would end. She said: "I will search everywhere for the man who had sex with me". But nowhere could she find the man who had had sex with her."

177-181: His father replied to the boy; his father replied to Su-kale-tuda: "My son, you should join the city-dwellers, your brothers. Go at once to the black-headed people, your brothers! Then this woman will not find you among the mountains."

182-184: He joined the city-dwellers, his brothers all together. He went at once to the black-headed people, his brothers, and the woman did not find him among the mountains.

185-193: Then the woman was considering a second time what should be destroyed because of her genitals; Inanna was considering what should be done because of her genitals. She mounted on a cloud, took (?) her seat there and ... The south wind and a fearsome storm flood went before her. The pilipili (one of the cultic personnel in Inana's entourage) and a dust storm followed her. Abba-cucu, Inim-kur-dugdug, ... adviser ... Seven times seven helpers (?) stood beside her in the high desert. She said: "I will search everywhere for the man who had sex with me". But nowhere could she find the man who had had sex with her.

194-195: The boy went home to his father and spoke to him; Su-kale-tuda went home to his father and spoke to him:

196-205: "My father, the woman of whom I spoke to you, this woman was considering a second time what should be destroyed because of her genitals; Inanna was considering what should be done because of her genitals. She mounted on a cloud, took (?) her seat there and ... The south wind and a fearsome storm flood went before her. The pilipili and a dust storm followed her. Abba-cucu, Inim-kur-dugdug, ... adviser ... Seven times seven helpers (?) stood beside her in the high desert. She said: "I will search everywhere for the man who had sex with me". But nowhere could she find the man who had sex with her."

206-210: His father replied to the boy; his father replied to Su-kale-tuda: "My son, you should join the city-dwellers, your brothers. Go at once to the black-headed people, your brothers! Then this woman will not find you among the mountains."

211-213: He joined the city-dwellers, his brothers all together. He went at once to the black-headed people, his brothers, and the woman did not find him among the mountains.

214-220: Then the woman was considering a third time what should be destroyed because of her genitals; Inanna was considering what should be done because of her genitals. She took a single ... in her hand. She blocked the highways of the Land with it. Because of her, the black-headed people ... She said: "I will search everywhere for the man who had sex with me". But nowhere could she find the man who had had sex with her.

221-222: The boy went home to his father and spoke to him; Su-kale-tuda went home to his father and spoke to him:

223-230: "My father, the woman of whom I spoke to you, this woman was considering a third time what should be destroyed because of her genitals; Inanna was considering what should be done because of her genitals. She took a single ... in her hand. She blocked the highways of the Land with it. Because of her, the black-headed people ... She said: "I will search everywhere for the man who had sex with me". But nowhere could she find the man who had had sex with her."

231-235: His father replied to the boy; his father replied to Su-kale-tuda: "My son, you should join the city-dwellers, your brothers. Go at once to the black-headed people, your brothers! Then this woman will not find you among the mountains."

236-238: He joined the city-dwellers, his brothers all together. He went at once to the black-headed people, his brothers, and the woman did not find him among the mountains.

239-244: When day had broken and Utu had risen, the women inspected herself closely, holy Inanna inspected herself closely. "Ah, who will compensate me? Ah, who will pay (?) for what happened to me? Should it not be the concern of my own father, Enki?"

245-249: Holy Inanna directed her steps to the abzu of Eridu and, because of this, prostrated herself on the ground before him and stretched out her hands to him: "Father Enki, I should be compensated! What's more, someone should pay (?) for what happened to me! I shall only re-enter my shrine E-ana satisfied after you have handed over that man to me from the abzu."

250: Enki said, "All right!" to her. He said, "So be it!" to her.

251-255: With that, holy Inanna went out from the abzu of Eridu. She stretched herself like a rainbow across the sky and reached thereby as far as the earth. She let the south wind pass across, she let the north wind pass across. From fear, Su-kale-tuda tried to make himself as tiny as possible, but the woman had found him among the mountains.

256-261: Holy Inanna now spoke to Su-kale-tuda: "How ...? ... dog ...! ... ass ...! ... pig ...!”

262-281: Su-kale-tuda replied to holy Inanna: "My lady (?), I was to water garden plots and build the installation for a well among the plants, but not a single plant remained there, not even one: I had pulled them out by their roots and destroyed them. Then what did the stormwind bring? It blew the dust of the mountains into my eyes. When I tried to wipe the corner of my eyes with my hand, I got some of it out, but was not able to get all of it out. I raised my eyes to the lower land and saw the exalted gods of the land where the sun rises. I raised my eyes to the highlands and saw the exalted gods of the land where the sun sets. I saw a solitary ghost. I recognised a solitary god by her appearance. I saw someone who possesses fully the divine powers. I was looking at someone whose destiny was decided by the gods. In that plot – had I not approached it three or six hundred times before? – there stood a single shady tree at that place. The shady tree was a Euphrates poplar with broad shade. Its shade was not diminished in the morning, and it did not change either at midday or in the evening."

282-289: "Once, after my lady had gone around the heavens, after she had gone around the earth, after Inanna had gone around the heavens, after she had gone around the earth, after she had gone around Elam and Subir, after she had gone around the intertwined horizon of heaven, the mistress became so tired that when she arrived there she lay down by its roots. I noticed her from beside my plot. I had sex with her and kissed her there. Then I went back to beside my plot."

290-295: When he had spoken thus to her, ... hit ... ... added (?) ... ... changed (?) him ... She (?) determined his destiny ..., holy Inanna spoke to Su-kale-tuda:

296-306: "So! You shall die! What is that to me? Your name, however, shall not be forgotten. Your name shall exist in songs and make the songs sweet. A young singer shall perform them most pleasingly in the king's palace. A shepherd shall sing them sweetly as he tumbles his butter-churn. A young shepherd shall carry your name to where he grazes the sheep. The palace of the desert shall be your home."

307-310: Su-kale-tuda ... Because ... destiny was determined, praise be to ... Inanna!

Conclusion

According to some scholars (notably Konrad Volk), the poem is a mythic retelling of the fall of the Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great (represented by Inanna) to the southern states of Babylonia and the Gutians (imagined as Su-kale-tuda). Scholar Jeffrey L. Cooley, among others, sees the story as an astral myth explaining why the planet Venus (associated with Inanna) moves across the sky as it does and, sometimes, seems to disappear. Scholar Gwendolyn Leick claims one cannot attribute human actions – such as rape – to divine figures literally, as myths are meant to be understood figuratively, and so the 'rape' of Inanna must have some other meaning besides the obvious.

Whatever merit these interpretations may or may not have, the simplest and, therefore, most likely reading of the poem is a condemnation of the act of rape. Su-kale-tuda is presented from his first appearance as a sorry loser who cannot even manage a garden as well as a raven and violates the laws of hospitality by raping a young woman who has sought rest in his garden under the one tree he does not seem to have had anything to do with. His father, instead of forcing him to face up to what he has done and accept punishment, encourages him to hide, bringing the three punishments upon the land.

As the poem makes clear, however, there is no hope of hiding from divine justice for a crime as serious as rape. Su-kale-tuda is caught by Inanna and sentenced to death but condemned to live in the memory of others eternally as a rapist who, for no apparent reason other than lust and, perhaps, his own sense of powerlessness and ineptitude, violated a goddess. Whenever this poem would have been performed, the men hearing it would have been presented with a powerful warning against doing the same to any young woman they could just as easily have protected.