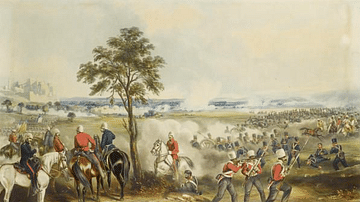

The Battle of Ferozeshah (aka Forezeshur) on 21-22 December 1845 was one of four major battles during the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-6) between the Sikh Empire and the British East India Company (EIC). The British relentlessly attacked the Sikh defensive positions and, thanks to the Sikh commanders' duplicitous ineptitude, gained a marginal victory with high casualties on both sides.

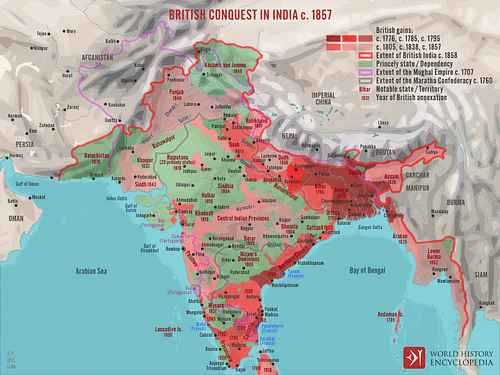

The war continued with similarly bloody encounters to Ferozeshah until the British won the war in March 1846. The territories of the Sikh Empire were reduced, and an EIC resident was installed to supervise the ruling maharaja. After the Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9), the British annexed the Punjab completely and so were finally in control of all of India.

First Anglo-Sikh War

The British East India Company had started as a trading company but by the mid-18th century, it had begun to look like the colonial arm of the British Crown in India with its territorial expansion across the subcontinent. The Company had won vital encounters with rival powers like the 1757 Battle of Plassey and the 1764 Battle of Buxar, which gave the British a vast and regular income in local taxes, besides other riches. The EIC kept on expanding and defeated the southern Kingdom of Mysore in the three Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799). Intertwined with those wars was a long-running contest with the Maratha Confederacy of Hindu princes in central and northern India. The EIC once again emerged victorious after the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819). Next came expansion in the far northeast and more victories in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-1815) and what turned out to be three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-1885). The next and final target of the EIC was northwest India and the Punjab.

The Punjab, located in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, is an area which today covers parts of Pakistan and India. It was the heartland of the Sikhs, who had established a state of sorts in the 18th century following the gradual decline of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). Sikh territories were divided between 12 misls or armies, each led by a chief who collectively formed a loose confederation. The greatest of Sikh leaders was Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), the 'Lion of Lahore'. He forged the Sikh Empire by modernising the army and conquering Multan and Kashmir (1819), Ladakh (1833), and Peshawar (1834). This expansion rang alarm bells in the offices of the East India Company, especially after their failure in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42) to the north. In 1839, the Sikhs, Afghans, and British signed a treaty to protect existing borders. Ranjit Singh died in June 1839, and political turmoil weakened the Sikh government's control over its own army. Rajit Singh's youngest son, Duleep Singh (l. 1838-1893), was selected as the new Sikh ruler in 1843, but as he was but a child, his mother, Jind Kaur (aka Rani Jindan, d. 1863), ruled as regent. Jind Kaur supported a military escapade against the British since; even if the Sikhs lost, this would cut the army down to size, perhaps ending the interference of the generals in government affairs and certainly reducing the threat of a military coup.

The EIC noted with interest this weakening of the Sikh state and took the opportunity to take over the Sindh province (southwest of the Punjab) in 1843. Confident that some of the Sikh misls in the east supported closer ties with the EIC, the British prepared for war in the Punjab and amassed an army of 40,000 men to the southeast of the Sikh state. In the wider world of empires, the British no longer considered the Sikh Empire a useful buffer zone in case of expansion of the Russian Empire into Afghanistan and northern India – the so-called Great Game. To retain their independence, the Sikhs would have to wage war against the most formidable military force in India: the armies of the East India Company.

On 11 December 1845, a large Sikh army crossed the southern frontier into EIC territory. This action broke the terms of the 1809 treaty, and so the EIC declared war on the Sikh Empire on 13 December. So the First Anglo-Sikh War began. The first battle of the war was at Mudki on 18 December 1845, which, thanks to numerical superiority and despite the skilled Sikh artillery batteries and sniper fire, the EIC won. Many of the British officers had believed the Sikhs would hastily retreat when the fighting started, but the bloody Battle of Mudki showed beyond doubt that this was going to be a war of attrition.

Opposing Armies

The British had at their disposal a total of 54,000 men, but these were dispersed around the Punjab in various army groups. The commander-in-chief of the EIC was the aged Irishman Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Gough (1779-1869), a crusty old veteran who believed in full-frontal bayonet charges on the enemy despite the high casualties such a strategy brought when fighting an equally well-equipped and courageous enemy as the Sikhs. To complicate the command structure, the man in charge of the East India Company, the Governor-General Lord Hardinge (in office 1844-48), was so keen to see action, he placed himself as Gough's second-in-command.

The EIC British soldiers, sepoys (Indian infantry), Gurkhas (from Nepal), and cavalry were all confident, given their long run of successes in the past half-century. Both the EIC and Sikh armies were well-equipped with cap-ignited muskets, more traditional breech-loading muskets, bayonets, swords, and cannons of all sizes.

The Sikh army, known as the Khalsa, had been well-trained by European mercenaries. By 1845, the Sikh army had some 6,200 cavalry, 70,000 infantry, and 500 artillery pieces. This core army was increased by raising local levies and employing irregular untrained troops and cavalry. Finally, there was a unit of 1,000 cavalry known as the Akalis, who were religious fanatics who fought bravely but rarely accepted to take battle orders. A typical Sikh army brigade was composed of around 3,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry, and 35 cannons, making them efficient, compact, and mobile fighting units.

A weakness of the Sikh army was the ill-discipline which had beset it during the turbulent post-Ranjit Singh period. Another problem was that many commanders had been selected for their political allegiance rather than their martial abilities. Even worse, the Sikh commander at Ferozeshah was Lal Singh (d. 1866). Post-war events reveal that Lal Singh may have been lacking in offensive-minded warfare because he wanted a prominent position in the new British-dominated Punjab.

Ferozeshah

After the Battle of Mudki, the Sikh army withdrew to ready-prepared fortified positions at Ferozeshah. Gough, never the most patient of commanders, did not want his men to ponder the discouraging fatalities at Mudki, and so after a few days of rest, he marched his army to Ferozeshah early on the morning of 21 December. His force was ultimately joined by 5,000 fresh men commanded by Major-General Sir John Littler (1783-1856). The total EIC force was composed of around 18,000 men and 69 guns.

The Sikh army numbered some 22,000 men and had over 100 cannons. The Sikhs were protected on three sides by defensive earthworks; inside this perimeter was the village of Ferozeshah. The main front was protected by a ditch 1 metre (3.3 ft) deep and 2 metres wide. They had taken the precaution of clearing away a large area in front to remove cover the enemy might use during an attack. The Sikhs had also planted random mines in the approach to their positions. The two weak points were the absence of earthworks on the northern side and the sheer length of the defences, which meant the army was spread out relatively thinly.

Battle – Day 1

Prior to the battle, Governor-General Hardinge wanted to delay an attack and wait for reinforcements (Littler's army), but Gough was adamant to proceed in case the Sikhs benefitted themselves from adding to their army. Hardinge pulled rank, and Gough was obliged to wait a few more hours. The British finally attacked in the mid-afternoon of 21 December. The British were already taking a risk by starting the battle more than halfway through the shortest day of the year, and they lengthened the odds of success further by Gough inexplicably charging the strongest point of the Sikh defences, the southern wall. The only possible explanation for this move is that Gough feared the time taken to assemble the army to attack another side of the Sikh defences might have permitted the expected Sikh reinforcements to arrive.

The fighting began with the usual artillery barrage from both sides. The skill of the Sikh gunners was quickly evident as they "fired at a considerably higher rate, three shots for every two they received in reply" (Smith, 47). This imbalance and the fact that the Sikh cannons were larger, eventually resulted in the British cannons being all put out of action. Gough then sent in his infantry, again, attacking the south side of the Sikh defences and using fixed bayonets.

The Sikh cannon fire, now sending grapeshot across the battlefield, was ferocious. In one stunning barrage, the Sikhs removed 260 men of the British 62nd Regiment in a mere ten minutes. The gunpowder weapons caused terrible wounds, smashing limbs, decapitating or cutting in half soldiers as they stood, even wiping out several men with the same shot. Eventually, the persistence of the British meant they broke through the Sikh defences, but then Sikh infantry troops, arranged for that eventually, drove the British back out of the defensive rectangle. EIC troops withdrawing now confused the progress of those brigades still advancing as the battlefield became more chaotic. The Sikh defences were once more breached at certain points. The old veteran Gough led from the front, wearing his own odd choice of battledress – a long white overcoat with a matching pith helmet. His tactics may have been suspect but certainly not his courage.

Within the Sikh defensive line, the fighting continued in and around the Sikh camp with Sikh snipers using the cover of the tents to pick off their targets. The British cavalry was now in the fray and also made it into the enemy camp, but their freedom of movement was impeded by the vast arrangements of stores and tents. Meanwhile, the Sikh cannons kept on firing. Even when charged down by cavalry or overwhelmed by infantry, the Sikh gunners kept at their posts and maintained their fire until killed. Adding to the confusion, many EIC troops were distracted as they began to look for much-needed water and food several hours into the battle.

Darkness fell and the fighting paused, but the night of the 21st was an ordeal for everyone with bitterly cold temperatures. The British had no means of protecting themselves from the cold since Gough had ordered the tents to be left behind that morning in order to speed up the march to Ferozeshah. Most of the soldiers did not even have their greatcoats. Fires could not be lit as they only attracted the attention of Sikh snipers. The battle hung in the balance, with many thinking it had been lost and others of the opinion that it had been won. It became clearer, though, in the bright moonlight, that the fighting must continue the next day to decide the issue.

Battle – Day 2

The British forces were in disarray and exhausted, but the Sikh army did not press its advantage. The Sikhs remained behind their defences and the cavalry remained totally inactive. The Sikh commander Lal Singh had thought an EIC victory only a matter of time in the First Anglo-Sikh War. Consequently, he seems to have conducted the campaign in such a way as to minimise the effectiveness of the Sikh army. Lal Singh even ordered large numbers of his men to withdraw from the defensive lines during the night. Still the Sikh cannons kept firing into the darkness on a bitter and despairing night for the British, as here summarised by Lieutenant Bellars of the 50th Regiment:

A burning camp on one side of the village, mines and ammunition wagons exploding in every direction, the loud orders given to extinguish the fires as the sepoys lighted them, the volleys given should the Sikhs venture too near, the booming of the monster guns, the incessant firing of the smaller ones, the continued whistling noise of the shell, grape and round shot, the bugles sounding, the drums beating, and the yelling of the enemy, together with intense thirst, fatigue and cold, and not knowing whether the rest of the army were the conquerors or conquered – all contributed to make this night awful in the extreme.

(Bruce, 142)

At 7.00 a.m. the British attacked again, and this time their progress went much better than the previous day. The Sikh troops that still manned the defences fought bravely, but their depleted numbers meant the camp was soon overrun. The exhaustion of the British and the temptation of the plentiful supplies in the Sikh camp meant the retreating enemy was not pursued.

Just as it seemed the British had won the battle, the Sikh commander Tej Singh (1799-1862) arrived at Ferozeshah with a fresh army, which immediately began to bombard the British with cannon fire. Tej Singh, like Lal Singh, was convinced of the futility of the war, and his delay in arriving at the battle is suggestive. An even clearer signal of Tej Singh's loyalties was his order to retreat and not fight the severely weakened EIC army, even if it was now using the defences the Sikh army had used the previous day. Incredibly, after seemingly all but defeated, Gough had engineered a famous victory.

In the 36 hours of battle, the EIC army suffered perhaps between 2,500 and 3,000 men dead or wounded. More casualties came after the battle as the Sikh camp had been heavily mined, and these hidden devices claimed many unfortunate soldiers confident the danger to life and limb had passed. It was a marginal victory for the EIC, given the high casualties. Victory had come from the bravery of the EIC troops charging into the face of terrific fire and the Sikh commanders' ineptitude and refusal to employ the cavalry or fight on. Significantly, both Lal Singh and Tej Singh, as they had hoped, secured high administrative positions when the British took over the Punjab.

Aftermath

In the third major engagement of the war, Major-General Harry Smith (1787-1860) oversaw another British victory at the Battle of Aliwal on 28 January 1846. Then, on 10 February, General Gough's ability to inspire his men and the fact that he had gathered about him the largest army yet seen in the war gave him victory at the Battle of Sobraon. This battle ended the war. Under the Treaty of Lahore, signed on 9 March, the EIC established the Punjab as a 'sponsored state', and parts of the Sikh Empire came under direct EIC rule. The EIC received a massive indemnity payment; they also took over Jammu and Kashmir (as part payment of the indemnity).

Unrest lay beneath the surface, though, in the Punjab. Certain Sikh chiefs felt they had been let down by their generals in the field during the first war (which indeed they had been), and they wanted a second crack at the British. Given the crushing terms of the Treaty of Lahore, the Sikhs had little to lose but potentially much to gain in another war. The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) began in April 1848 and was largely fought in the south and west of what had once been the Sikh Empire. Once again, it was a short and bloody campaign with one siege and three major battles, including the Battle of Chillianwala on 13 January 1849, which resulted in high losses on both sides. The EIC was victorious yet again in this war. The whole of the Punjab was annexed in March 1849, and the EIC now reigned supreme in India.