The Battle of Aliwal on 28 January 1846 saw the British East India Company (EIC) defeat the Sikh Empire. One of four major battles during the First Anglo-Sikh War (1845-6), Aliwal was a decisive victory where the EIC's Bengal Lancers cavalry established their formidable reputation. After one more victory at the Battle of Sobraon, the war was won.

The First Anglo-Sikh War

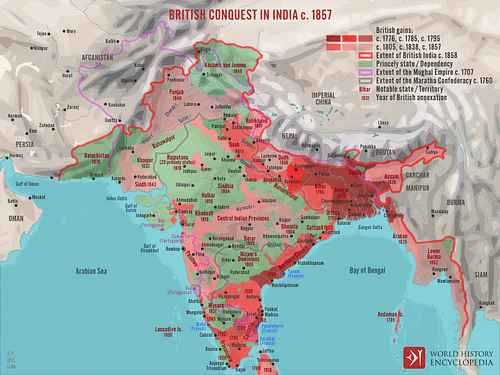

By the mid-18th century, the British East India Company had started to look very much like the colonial arm of the British Crown in India with its territorial expansion across the subcontinent. The Company had won vital encounters with rival powers like the 1757 Battle of Plassey and the 1764 Battle of Buxar, which gave the British a vast and regular income in local taxes, besides other riches. The EIC kept on expanding and defeated the southern Kingdom of Mysore in the three Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799). Intertwined with those wars was a long-running contest with the Maratha Confederacy of Hindu princes in central and northern India. The EIC once again emerged victorious after the three Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1819). Next came expansion in the far northeast and more victories in the Anglo-Nepalese War (1814-1815) and what turned out to be three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824-1885). The next and final target of the EIC was northwest India and the Punjab.

The Punjab, located in the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, is an area which today covers parts of Pakistan and India. It was the heartland of the Sikhs, who had established a state of sorts in the 18th century following the gradual decline of the Mughal Empire (1526-1857). Sikh territories were divided between 12 misls or armies, each led by a chief who collectively formed a loose confederation. The greatest of Sikh leaders was Ranjit Singh (1780-1839), the 'Lion of Lahore'. He forged the Sikh Empire by modernising the army and conquering Multan and Kashmir (1819), Ladakh (1833), and Peshawar (1834). This expansion rang alarm bells in the offices of the East India Company, especially after their failure in the First Anglo-Afghan War (1838-42) to the north. In 1839, the Sikhs, Afghans, and British signed a treaty to protect existing borders. Ranjit Singh died in June 1839, and political turmoil weakened the Sikh government's control over its own army. Rajit Singh's youngest son, Duleep Singh (l. 1838-1893), was selected as the new Sikh ruler in 1843, but as he was but a child, his mother, Jind Kaur (aka Rani Jindan, d. 1863), ruled as regent. Jind Kaur supported a military escapade against the British since, even if the Sikhs lost, this would cut the army down to size, perhaps ending the interference of the generals in government affairs and certainly reducing the threat of a military coup.

The EIC noted with interest this weakening of the Sikh state and took the opportunity to take over the Sindh province (southwest of the Punjab) in 1843. Confident that some of the Sikh misls in the east supported closer ties with the EIC, the British prepared for war in the Punjab and amassed an army of 40,000 men to the southeast of the Sikh state. In the wider world of empires, the British no longer considered the Sikh Empire a useful buffer zone in case of expansion of the Russian Empire into Afghanistan and northern India – the so-called Great Game. To retain their independence, the Sikhs would have to wage war against the most formidable military force in India: the armies of the East India Company.

The First Anglo-Sikh war broke out when a large Sikh army crossed the Sutlej River into EIC territory on 11 December 1845. The first confrontation was the Battle of Mudki on 18 December. The EIC was victorious there and again at the Battle of Ferozeshah (aka Forezeshur) on 21-22 December. There were so many casualties on both sides, Ferozeshah was a marginal victory only, and then largely because the Sikh commanders, with one eye on a post-war regime change, did not apply themselves to the task and refused to go on the offensive. The Sikhs did inflict some serious damage when a British column passed too close to the fort of Bhudowal on 21 January. The EIC army had been treacherously guided to within firing range of the Sikh artillery and suffered a bad mauling.

The Two Armies

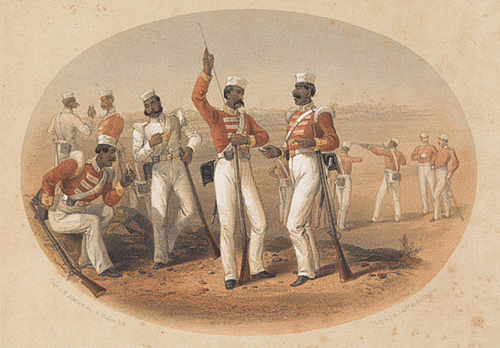

The armies of the EIC had enjoyed a string of victories thanks to its winning combination of British troops, regular British army regiments, sepoy (Indian) and Gurkha (Nepalese) infantry, cavalry, and well-trained artillery units. The principal weapon was the musket, either breech-loaded or the more modern version with a quicker cap-ignited mechanism. The preferred tactic remained, though, the infantry charging at the enemy with fixed bayonets. The EIC commander-in-chief was Lieutenant-General Sir Hugh Gough (1779-1869), a crusty old veteran who led from the front. Major-General Harry Smith (1787-1860) commanded the EIC army at Aliwal, which numbered around 10,000 men and which possessed 32 cannons.

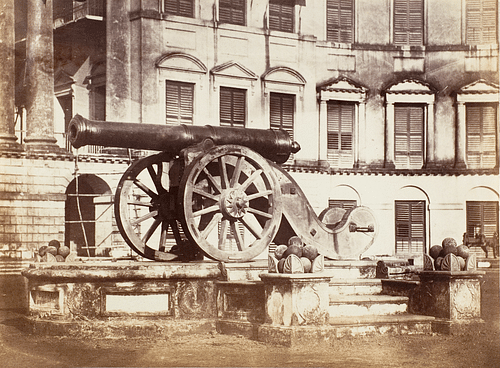

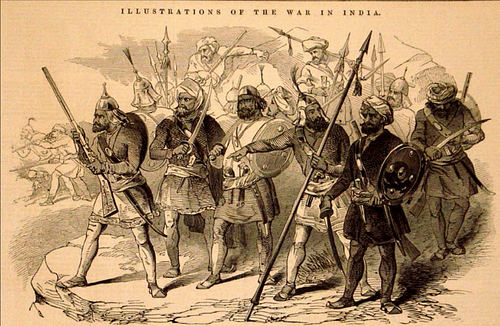

The Sikh army, known as the Khalsa, was as well-trained as the EIC army, thanks to the employ of European mercenaries. It was also well-equipped (although its cap-ignited muskets were inferior replicas) and had far more and bigger cannons than the EIC force could mobilise in this part of India. These monster cannons were dragged to the battlefield using huge teams of bullocks and elephants. A typical Sikh army brigade was composed of around 3,000 infantry, 1,500 cavalry, and 35 cannons making them efficient, compact, and mobile fighting units. The commander-in-chief of the Sikh Empire was Tej Singh (1799-1862), a leader of experience and ability. The direct commander at Aliwal was General Ranjodh Singh (aka Ranjur Sing, d. 1872), and he had at his disposal around 14,000 men and 75 cannons.

Battle Lines

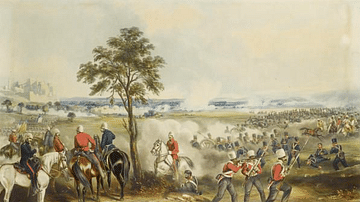

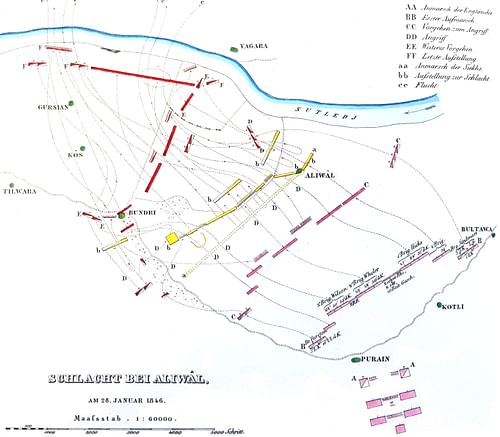

The two armies clashed along a long curved front 1.5 miles (2.5 km) in length not far from the village of Aliwal. The battlefield was a wide grassy plain with some trenches prepared by the Sikh army for its own defence. Ranjodh Singh spread his cannons all along his battle line. Both armies had their cavalry positioned on the wings. The Sikh army had the Sutlej river just one mile (1.6 km) behind it, a fact that would hamper the troop movements during the battle.

Mid-morning of 28 January, both sides exchanged artillery fire for around 30 minutes. Smith then concentrated his infantry to attack the right side of the battlefield, and the Sikh lines gathered around the moderately fortified village of Aliwal. The Sikh artillery continued to fire into the advancing EIC infantry. The devastating effectiveness of the Sikh gunners was recorded by one Tom Pierce: "The first man that was killed stood only a few yards from me. A 9-pound shot took his head from his body. I felt rather sick at seeing the men fall by threes and fours around me." (Bruce, 166)

Both sides' cavalry were involved around Aliwal, but the British infantry gained the upper hand over their Sikh counterparts, mostly as these were less-disciplined irregulars. Smith had his artillery units move forward to keep pace with the progress of his infantry and cavalry.

The Charge of the 16th Lancers

At this point, Ranjodh Singh had already left the battlefield, and his troops were left to reorganise themselves into a second line further to the rear and around the village of Bhundri. The EIC cavalry unit that grabbed the plaudits after the battle was the 16th Lancers, which operated on the left flank of the army and repeatedly charged the Sikh infantry. The Sikh troops had formed their traditional defensive arrangement of equilateral triangles. Sergeant William Gold (who incorrectly describes the formation as a square) gives the following account of the action:

We had to charge a square of infantry. At them we went, the bullets flying around like a hailstorm. Right in front of us was a big sergeant, Harry Newsome. He was mounted on a grey charger, and with a shout of "Hullo, boys, here goes for death or a commission," forced his horse right over the front rank of kneeling men, bristling with bayonets. As Newsome dashed forward he leant over and grasped one of the enemy's standards, but fell from his horse pierced by 19 bayonet wounds.

Into the gap made by Newsome we dashed, but they made fearful havoc among us. When we got to the other side of the square our troop had lost both lieutenants, the cornet, troop sergeant-major, and two sergeants. I was the only sergeant left.

(Holmes, 367-8)

The EIC cavalry, infantry, and artillery combined to smash this second line of defence as well as the reserves being kept in the Sikh camp behind. Some of the Sikh artillery units had managed to regroup to defend this new line, but they only managed to get off one salvo before they were overwhelmed by the British advance.

The British Victory

The entire Sikh army, now in total disarray, fled the field and crossed the Sutlej river using whatever boats could still be found from the original crossing the army had made some days before. All of the Sikh cannons were captured in the chaos, and the British artillery – some 20 cannons – were moved up to maintain a fierce fire at the retreating army. The British artillery blew several boats out of the water, and the persistent barrage prevented the Sikhs from regrouping on the far bank. By around 5.20 p.m., Smith had won an important victory, especially after the debacle at Bhudowal; he described the battle as a

Stand-up, gentlemanlike battle, a mixing of all arms and laying-on, carrying everything before us by weight of attack and combination, all hands at work from one end of the field to the other.

(Holmes, 65)

It is perhaps for this reason that the Battle of Aliwal was frequently described as 'the battle without a mistake'. Another reason is that there were relatively few casualties compared to earlier battles in the war. The Sikhs suffered hundreds of dead and wounded (but not the thousands in other battles), and the EIC army counted only 151 fatalities and 413 wounded (and 25 missing in action). The 16th Lancers took the most casualties at Aliwal in proportion to their total number: 59 dead, 83 wounded, and 101 horses killed or wounded.

Aftermath

The First Anglo-Sikh War went on, but the Sikh Empire was looking increasingly fragile after losing three major battles in a row. On 10 February, General Gough's ability to inspire his men and the fact that he had gathered about him the largest army yet seen in the war gave him victory at the Battle of Sobraon, where the last Sikh army south of the Sutlej was destroyed. This battle ended the war. Under the Treaty of Lahore, signed on 9 March, the EIC established the Punjab as a 'sponsored state', and parts of the Sikh Empire came under direct EIC rule. The EIC received a massive indemnity payment; they also took over Jammu and Kashmir (as part payment of the indemnity).

Unrest lay beneath the surface, though, in the Punjab. Certain Sikh chiefs felt they had been let down by their generals in the field during the first war (which indeed they had been), and they wanted a second crack at the British. Given the crushing terms of the Treaty of Lahore, the Sikhs had little to lose but potentially much to gain in another war. The Second Anglo-Sikh War (1848-9) began in April 1848 and was largely fought in the south and west of what had once been the Sikh Empire. Once again, it was a short and bloody campaign with one siege and three major battles, including the Battle of Chillianwala on 13 January 1849, which resulted in high losses on both sides. The EIC was victorious yet again in this war. The whole of the Punjab was annexed in March 1849, and the EIC now reigned supreme in India.

Besides being a key turning point in the Anglo-Sikh Wars, the Battle of Aliwal had a further cultural impact. The daring exploits of the 16th Lancers were the beginning of a myth of the all but invincible 'Bengal Lancers' that became something of a cliche of warfare in India thereafter. This was perpetuated thanks to hugely successful books like the autobiographical The Lives of a Bengal Lancer by Francis Yeats-Brown (published in 1930). In 1935, the book was made into the critically-acclaimed Hollywood film of the same title, starring Gary Cooper.