The HMS Gloucester was wrecked in the North Sea, about 30 miles off the shore of Norfolk, England, shortly after dawn on 6 May 1682. It was a warship in the navy of Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), and at the time of its loss, it was the flagship of a small fleet of ten ships on their way to Scotland to fetch Mary of Modena, the pregnant wife of James, Duke of York, the brother of Charles and the future James II of England (r. 1685-1688).

James Recalled from Exile

James and his wife had been in virtual exile for the best part of three years because they were Catholics, and a vitriolic anti-Catholic mood had spread through the nation in the late 1670s. But Charles, aware of his own failing health and his lack of a legitimate child, was becoming increasingly anxious to rehabilitate James, as his heir, at the center of government.

James, for his part, now that he was being allowed back into London was anxious to make a great show of his return to center stage. So, instead of a low-key voyage in a single royal yacht, which would have been his more usual style of transport, he decided to travel in a third-rate warship, accompanied by five other warships and four royal yachts. The third-rates were the favored ships for longer voyages, faster and more nimble than their larger consorts, and more comfortable and capacious than the smaller ones. The disaster, however, that ensued, and which resulted in the loss of over 150 lives, caused a great furore at the time, and has been a subject of much conjecture and controversy ever since.

On its final voyage, the Gloucester was carrying not just James, but a large coterie of his most loyal friends and supporters, aristocrats like the Earl of Roxburgh, merchants such as Sir James Dick who was Lord Provost of Edinburgh, the slave trader William Freeman, the famous scientist and physician Sir Charles Scarborough, and military men like John Churchill, who was later to become the Duke of Marlborough. As well as these notables, a large number of James' royal household were on board, together with a handpicked selection of royal musicians for entertainment on route, and his own huntsmen for his amusement when he arrived. In addition to all these passengers, there were nearly 200 seamen on the ship.

But what makes this disaster unique is that the entire drama was closely observed by the great diarist Samuel Pepys. Pepys watched events unfold from the poop deck of a yacht which had managed to anchor close by. The horror of it made a great impression on him and he returned to it on several occasions both in his letters and his naval minutes.

Departure

Early on the morning of the 4th May the royal yachts Mary, Charlotte, Katherine, and Kitchin, together with the small sixth-rate Lark, sailed out of the Thames Estuary, where they were joined by the larger warships Gloucester, Happy Return, Pearl, Ruby, and Dartmouth, which had come round from Portsmouth. James, his entourage, and the royal luggage were then transferred from the yacht Mary to the Gloucester. There followed the usual firing off of cannons to mark the importance of the occasion and the fleet got underway for Edinburgh around 11:00 a.m., the wind coming from the south.

The voyage was a shambles from the very start. By 8:00 p.m., they had only managed to sail about 25 miles, and as the weather was murky and wet, the decision was taken to moor up for the night. The Gloucester fired a gun intending to signal that the fleet should close and drop anchor. Three out of the ten ships interpreted this signal as requiring them to immediately tack seawards. As a result, they became lost from the main fleet and never rejoined it. One of them called the Ruby under Captain Allin ran onto the dangerous Galloper sands in the darkness, but luckily the ship came off again without serious damage.

The Gloucester and the six ships that were still in attendance did not weigh anchor until 8:00 the following morning, although it had been daylight for at least four hours. There has been much speculation about the reasons for such a late start. The most obvious explanation is that there had been so much partying during the previous evening that there were a large number of hangovers.

At 8:00 p.m. that evening, shortly after dusk, Captain Gunman, in charge of the Mary yacht which was sailing out in front, ran up under the Gloucester's stern. Gunman shouted that the fleet was heading far too close to the sandbanks off Yarmouth and "the pilot was mad if he did not tack off". It was the second such intervention Gunman had made that same evening. He later told his wife in a letter that he was so angry that he stamped and flung his hat on the ground. A huge row broke out. Eventually, the pilot on board the Gloucester, called Captain Ayres, who was the man supposedly in charge of the course that they were all following, was overruled. It was James himself who made the fatal decision, and the fleet tacked off further out to sea. Somewhat strangely the Captain of the Gloucester, Sir John Berry, did not offer an opinion.

Dangerous Sands

As darkness fell at the end of this second day of sailing, the Gloucester did not moor up. The weather was blustery, but the winds were blowing from a favorable direction. The diminished fleet of seven ships continued to sail at a speed of somewhere around 6 knots through the darkness. This was a very fast speed for large sailing ships at night time and is in marked contrast to the lack of activity of the previous night. But none of the various journals, letters, log books, or diaries offer an explanation for the sudden urgency.

At 4:00 a.m. the following morning, just as it was beginning to get light, the pilot, Captain Ayres, went off duty. The yacht Mary under Captain Gunman was still sailing out in front. Gunman also went off duty at 4:00 a.m. The belief on both ships was that they must by then have passed all the dangerous sands, including the notorious Leman and Ower. At 5:00 a.m., the Mary suddenly came into shallow water. They immediately tacked to the port and waved a flag from the poop deck to warn the Gloucester. But it was too late. Within a few minutes the Gloucester, following about half a mile behind, had crashed at speed into a sandbank.

James' Rescue

James was one of the first to be on deck after the striking, and for the first few minutes, he was hopeful that the ship might be saved. Sir George Legge, on the other hand, one of James' most trusted supporters, and his general Mr Fix-It, was anxious to get James disembarked as quickly as possible. James was, after all, the heir to the throne. The first priority had to be to save his life. Only after James was safely away could attention be given to getting the other passengers and the crew into rescue boats. Legge later told his son that even when James had finally agreed to evacuate, he spent far too long trying to save his strongbox:

My father with some warmth asked him whether there was anything in it worth a man's life. The Duke answered that there were things of so great consequence, both to the King and himself, that he would hazard his own life rather than it should be lost. (The Correspondence of Henry Hyde)

In the event, the strongbox had to be abandoned and went down with the ship. James was rowed in a small shallop to the Mary yacht which was moored at about half a mile away. A few of his closest supporters went with him including John Churchill. Large numbers of people, who were already floundering in the water, attempted to climb aboard. In order to stop the royal boat from being overwhelmed and everyone drowning, the order was given for those trying to climb in, to have their hands severed. It was not just James' rescue boat that was preserved from being swamped in this brutal manner. Sir James Dick was in a different boat, but he describes in a private letter the same desperate scramble for survival.

The majority of those who drowned were ordinary sailors but there were high profile losses as well, men like the 2nd Lieutenant on the Gloucester, James Hyde, son of the Earl of Clarendon, and Sir Joseph Douglas of Pompherton, and John Hope the laird of Hopton. The most distinguished person to drown was the Earl of Roxburgh. His young wife never forgave James for what she regarded as his betrayal in abandoning her husband, and for the next 71 years, she remained an embittered and inconsolable widow.

Aftermath

Criticism of James' actions was not limited to his concern for his strongbox. Bishop Burnet, a contemporary historian, who, for very obvious reasons, did not actually publish his account until after James lost the throne, accused him of saving only his priests and his pet dogs and of going off in a ship that could have held 80 more people. A careful study of what actually happened proves the bishop to have been wrong on all three counts. But his smear stuck and has been often repeated.

As soon as James had returned to London the entire Stuart public relations machine was cranked into action. Paintings were commissioned that depicted James' salvation as an act of divine providence. Medals were struck celebrating his steadfastness at a moment of crisis. Even more importantly, because they reached the widest audience, poems and panegyrics were written in large numbers. One by Nathaniel Wanley gives a good feel for the average content. He wrote that as soon as the sailors "perceived ... the Duke out of danger, they all of 'em threw off their caps and made loud acclamations and huzzahs of joy ... and in this rapture sunk to the bottom of the sea" (The Life of Lord Sothward, Bishop of Salisbury) There was even a rumor spread about that the sinking of the Gloucester was part of a republican plot to murder James. The alleged plan was that the ship's pilot, Ayres, had been commissioned to deliberately run the Gloucester onto a sandbank.

One of James's more astute pieces of political management that helped turn the Gloucester disaster into a personal success story, was that he ordered special bounty payments to be made to the widows of those sailors who had lost their lives. Bounty payments were not customarily paid to the dependent relatives of shipwrecked sailors, but only to those who died in battle. But in this instance, James ordered that an exception should be made. He wanted to be seen to be doing the generous thing.

It is through the bounty payment records that it is possible to learn much detail about the ordinary sailors who had been on board and who lost their lives. They were men like Thomas Smith, the deck swabber, who had just been released from debtor's gaol. His poor blind wife Joan, travelled to London to claim her money, but her paperwork was not in order, and she made the mistake of getting a friend to try and forge the necessary documents.

The pro-James campaign clearly worked. He ascended the throne three years later with very little in the way of opposition. But within another three years, he had squandered that goodwill, and in 1688, he was forced to flee the country in a most ignominious manner. After 1688, an entirely different version of the Gloucester sinking became dominant which painted James's actions in a far more damaging light.

Modern Research

Somewhat oddly, in view of all the controversy that has raged down the centuries, very little attention has ever been paid to what was most probably the main cause of the disaster, namely the deplorable state of contemporary cartography. The standard sailing directions that were in use at the time were John Seller's English Pilot. Different editions show the Leman and the Ower sandbanks, which was where the Gloucester wrecked, in a great variety of distances from the mainland, all of them wildly inaccurate by a distance of around 14 miles. No attempt had ever been made to actually plot the position of the sandbanks accurately. It is hardly surprising then that the unfortunate pilot, who ended up court-martialed and sentenced to life in Marshalsea Prison, believed that the Gloucester was safely past all the dangers.

One of the other great mysteries about the wreck of the Gloucester that has received very little attention up until now is why Samuel Pepys refused to go on the ship, despite being asked more than once by James himself to do so. This disaster cannot be properly understood without the closest attention being paid to his puzzling behavior before, during, and after the sinking.

The wreck was located in 2007. It is of immense historical and archaeological importance because of the extraordinary diversity of people who were on board at the time of its sinking, most of whom lost all their personal possessions, and many of them also their lives. A large number of amazing artefacts have already been recovered including a wine bottle with the coat of arms of the Washington family emblazoned on it, a forerunner of the Stars and Stripes flag. The bottle probably belonged to Sir George Legge who was married to a Washington. The debris field is now to be fully excavated by underwater archaeologists and a preliminary exhibition of recovered artefacts is being opened to the public in Norwich Castle Museum, England, from February 2023.

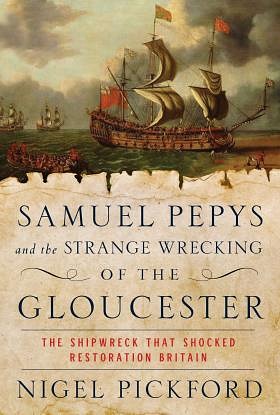

Nigel Pickford is a maritime historian who has researched historic shipwrecks for the last 40 years. He carried out the archival and navigational analysis that led to the discovery of the Gloucester. He has written numerous books on shipwrecks and is published by both Dorling Kindersly and National Geographic. 'Samuel Pepys and the Strange Wrecking of the Gloucester', Pegasus Publishing, is his latest work.