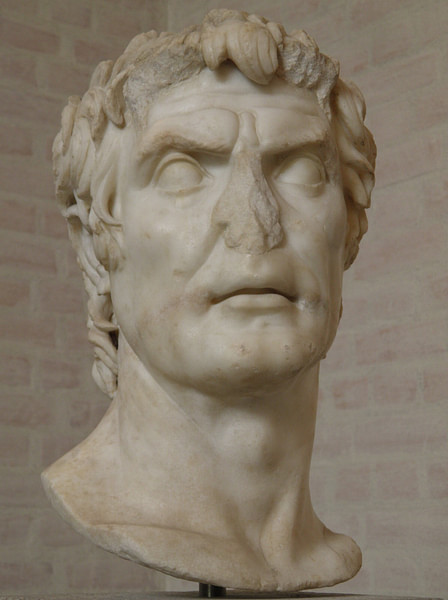

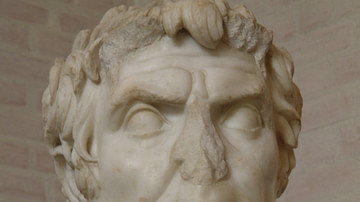

In 88 BCE, Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138-78 BCE) marched on Rome and entered the city's sacred inner boundary, the pomerium, bearing arms. Breaking this taboo, he sought to gain political power and control of the army of the East that had been offered to his enemy, Gaius Marius (c. 157-86 BCE). A second march occurred in 83-82 BCE when he assumed the title of dictator.

Early Career & Service under Marius

Lucius Cornelius Sulla was born into a noble patrician family in 138 BCE. Married three times, he has been described as physically striking as well as charming with a rare brilliance. Unfortunately, upon his father's death, he was left penniless. Historian Tom Holland in his book Rubicon stated that Sulla "gradually sunk into a world of seedy lodgings and some seedier companions" (61). According to historian Mike Duncan in his The Storm Before the Storm, Sulla was fluent in Greek and "highly literate in art, literature and history" (116). At the age of 30, his future looked promising when his stepmother died, leaving him with an inheritance that allowed him to enter upon a much-desired aristocratic career. Most historians agree that Sulla sought and gained prestige.

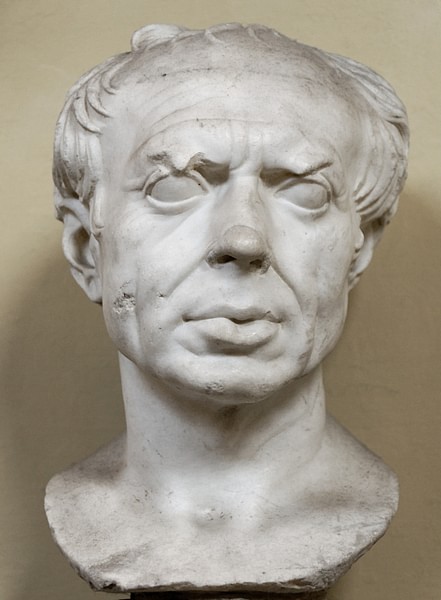

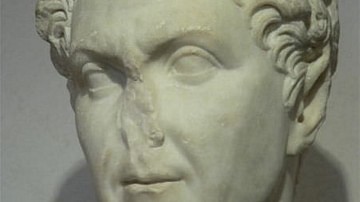

In 107 BCE, serving under the consul Gaius Marius (c. 157-86 BCE), Sulla travelled to Libya where he distinguished himself in the Numidian War. He acquired, through diplomacy and the treachery of King Bocchus I of Mauretania, the surrender of Jugurtha (r. 118-105 BCE), the king of Numidia; thereby ending the seven-year war. The defeated king was delivered in chains to Marius. The historian Plutarch (45/50 to 120/125 CE) wrote that the surrender of Jugurtha by Sulla "grieved" Marius, but not Sulla. The victorious commander was "by nature vainglorious" and had an appetite for distinction that "carried him to such a pitch of contention" (501).

In 104-103 BCE, he again served under Marius in Germania. Plutarch wrote that "Sulla, perceiving that Marius bore a jealous eye over him and would no longer afford him opportunities of action, but rather opposed his advance, attached himself to Catulus, Marius's colleague…" (502). Sulla had grown, by this time, to despise Marius; it was a mutual feeling. Quintus Lutatius Catulus, a worthy but not energetic general, trusted him with important commands and "he rose at once to reputation and power" (502).

In 98 BCE, believing his military achievements would entitle him to a career in the Roman government, he attempted to acquire a position as a praetor but failed. Plutarch wrote:

… thinking that the reputation of his arms abroad was sufficient to entitle him to a part in civil administration, he took himself immediately from the camp to the assembly, and offered himself as a candidate for a praetorship, but failed. (502)

Politically, Sulla was conservative – an Optimate – with an objective to restore the Roman Senate's traditional authority. In 97 BCE, he became praetor urbanus and was assigned to Cilicia in Asia Minor, remaining there until 92 BCE.

The Social War

Leaving Cilicia and returning to Rome, Sulla quickly learned that the reward for fame was to seize the opportunity for greater achievements and renown. In 89 BCE, Sulla took another giant step towards his ultimate goal: a consulship. During the Social War or War of the Allies (91-87 BCE), he joined with the Roman forces in opposition to the rebels (alae or allies) and quickly distinguished himself at the siege of Pompeii. In addition, he also forced the surrender of the rebels at Campania.

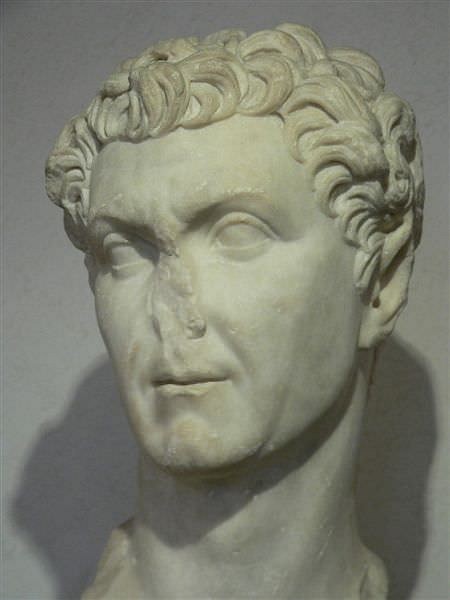

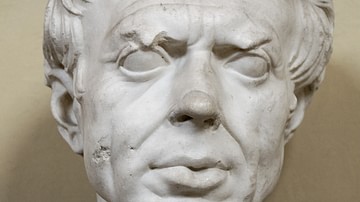

In the following year, at the age of 50 and as a reward for his Social War achievements, he became consul alongside Quintus Pompeius Rufus. Besides the consulship, he was given command of the Roman army in the East – a command that would soon become a war against the king of Pontus: Mithridates VI Eupator Dionysius (120-63 BCE). Mithridates had taken advantage of the Roman Republic's distraction in the Social War and exploited the hatred felt towards Rome by many of the eastern states. The war in the East had already cost numerous Roman citizens and Italians their lives. Sulla's consulship and his control of the army in the East fueled the hatred further between Sulla and the retired Marius who had long relished a war against the Pontus king for the riches and respect it would bring. Victory against Mithridates meant a triumph for Sulla and humiliation for Marius.

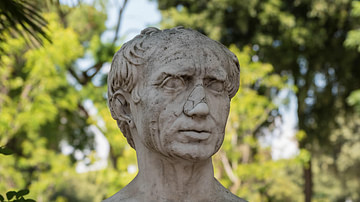

Rise of Sulpicius

In political opposition to Sulla was the tribune (and Populare) Sulpicius Rufus. Plutarch wrote that "He was cruel, bold, rapacious and in all of these points utterly shameless and unscrupulous" (505). The tribune had a personal agenda. Realizing his path to power was through the Italians, he proposed legislation that would grant Roman citizenship and rights to the allies – a measure Sulla and Rome strongly opposed. However, Sulpicius Rufus needed support to help get his measures through the Assembly. That help came from the willing but elderly Marius who had an agenda of his own: opposition to Sulla and a command in the East. If Sulpicius were successful, he promised he would give the eastern command to Marius.

These proposals led to clashes in the streets. Riots erupted throughout the city, and the cruel and bold Sulpicius and his anti-Senate mob were at the heart of them. Sulla and his army were stationed at Nola, a pro-ally city still resisting Rome. Returning to the city, Sulla and his co-consul Pompeius Rufus immediately staged an intervention, declaring a holiday (furiae) with all public houses closed, but this edict only further fueled discontent. The armed crowd turned hostile and, fearing for his life, Sulla sought the closest and safest refuge – the home of Marius on Palatine Hill. Unfortunately, Pompeius Rufus' son, who strongly defended his father, was a casualty of the mob.

After the riot was finally quelled, the Assembly met and passed Sulpicius' legislation. Supposedly Marius told Sulla that his only hope for safety was to allow Sulpicius' laws to pass. With Sulla returning to Nola and Pompeius Rufus forced to resign his consulship, things turned ugly in Rome. While Sulla was out of the city, Sulpicius withdrew his appointment to command in the East and gave it to Marius. Hearing rumors of his removal, Sulla addressed his army; they were outraged. If Marius took command and fought Mithridates, his veterans, not Sulla's, would receive the riches. Marius sent two military tribunes to remove Sulla from his command; they were both stoned to death. Sulla's next, and in his mind the only, move was to march on Rome. In Rome, Sulpicius took complete control, and the friends of Sulla were quickly identified and assassinated. Plutarch wrote that Marius "proceeded to put the friends of Sulla in the city to the sword, and rifled their goods. Every kind of removal and flight went on, some hastening from the camp to the city, others from the city to the camp" (506).

Sulla Marches on Rome

Leading an army of six legions, Sulla marched down the Via Appia to Rome. The Senate, hoping to broker peace, sent two praetors, Brutus and Servilius, to Sulla. When asked why he was marching on Rome, Sulla simply replied that he was defending the city from tyrants. What frightened the Senate most was that the troops were loyal to Sulla, not Rome. To enter the city, Sulla and his army had to cross the sacred inner boundary of Rome, the pomerium – a furrow supposedly plowed by the founder of the city, Romulus – within which no Roman citizen was allowed to bear arms. To cross it with an army was a religious taboo. This taboo caused a number of his officers and soldiers to desert Sulla – one exception was a quaestor and future commander named Lucius Licinius Lucullus (c. 117-57/56 BCE).

The Esquiline Gate soon fell to Sulla's troops. After Sulla seized the city gates, he paraded his army through the streets. Fire arrows sailed through the air. Among the commander's initial orders were that Sulpicius' laws were repealed, and Marius and Sulpicius were declared enemies of the state. Marius, temporarily seeking asylum in the Temple of Tellus, would escape to Africa, while Sulpicius would be killed by his servant – the servant would later be killed for betraying his master.

After a number of reform measures, Sulla saw to the naming of two new consuls: Gnaeus Octavius and Cornelius Cinna. Both swore to uphold Sulla's legislation. At this time, Sulla left to meet Mithridates and his army in Greece. However, shortly after Sulla left, Marius reentered Rome. Duncan wrote that for five days "the people of Rome cowered under a bloody terror" (211). Octavius was killed, and Marius was named the new consul but died soon after. The absent Sulla was indicted for the murder of Roman citizens. Although accused of being crazed with bloodlust, Marius settled personal vendettas but was no better or worse than anyone else. Pompeius Rufus escaped the city and was given the army of Pompey Strabo to command, but the change in command was not appreciated, and Pompeius was murdered.

As the city was plagued by chaos, Sulla unknowingly left one legion at Nola and headed east and engaged Mithridates in battle. Sulla defeated the Pontus king at Chaeronea and Orchomenos. The Roman commander Fimbria went on a rampage in Asia, nearly capturing Mithridates. Finally, in 83 BCE, Sulla and Mithridates met in person on an island in the Aegean. Mithridates agreed to peace but returned to Pontus and rebuilt his forces.

Sulla Returns to Rome

With peace having been reached, Sulla realized the need to return to Rome. The consul Cinna and his army made a futile attempt to stop Sulla, but Cinna was killed by his own mutinous troops. Another attempt came at the Colline Gate from the Samnites, an old enemy from the days of the Social War. While Marcus Licinius Crassus smashed the Samnite left, Sulla rallied his troops; the Battle of Colline Gate was won, with 3,000 prisoners taken and another 3,000 surrendered. The Campus Martius or Plain of Mars served as a temporary headquarters of Sulla before he entered the city. A massacre soon followed at the Circus Flaminius where the supposed prisoners of war were being held – the bodies were thrown into the Tiber.

In 82 BCE, Sulla entered the city and assumed the title of dictator, with both supreme authority and an indefinite term of office. He was immediately granted immunity for his action, both past and future. Simon Baker in his Ancient Rome wrote that Sulla "proceeded to wreak a brutal and violent revenge on the populists" (106). Proscription lists were posted in the Roman Forum; enemies were hunted down. Many were killed while others were forced to flee the city. Duncan wrote that 80 names were posted to be killed on sight, 220 came next, followed by a list of 800. Murder groups roamed the city. He wrote, "Far from relieving tension, the proscription lists blanketed Italy under a reign of terror." (247)

Aftermath

However, among Sulla's legislation was an increase in the size of the Senate from 300 to 600, the number of praetors was increased to eight, and the number of quaestors was increased to 20. Veterans were settled on the confiscated lands in Campania and Etruria. He gave the Senate control over the jury courts. He passed strict laws concerning the magistracies. Remembering his troubles with Sulpicius, tribunes were forbidden to present bills directly to the people's assembly. He also cancelled the grain ration. Having achieved much of what he wanted, he addressed the public assembly and requested the surname of Felix ("Lucky"). He retired to Campania in 79 BCE, dying there the following year. Despite a number of objections, Sulla received a public funeral.