To climatologists, the period of seven to twelve centuries ago was known as a "Climate Anomaly" or a "Warm Period" (800-1300 CE). To archaeologists, it was a time of great change, a period when cultural patterns were put into place that lasted into the modern era. Although the medieval period is better known in Europe and the Old World, it was a global phenomenon. It happened in the New World, too.

New World Cultures of the Warm Period

In the Mississippi valley, this was the era of the Mississippian culture. In North Mexico and the American Southwest, it encompassed the Puebloan, Hohokam, Mogollon, and early Casas Grandes cultures. In Mesoamerica, which is to say from about Culiacan, Mexico, on the Pacific coast to Tampico, Mexico, on the Gulf coast and south to Nicaragua, the era encompassed the Epi-Classic, Terminal Classic, and early Postclassic periods and included the so-called Toltec, Huastec, and Maya civilizations, among others. Whatever the names and whomever the people, all appear to have been part of a phenomenon – a cult or cults of Thunderers or Winds-that-bring-rain gods – that swept the continent over the course of 200-300 years.

The sweeping effects were profound, leaving lasting imprints on diverse peoples and their civilizations and establishing ways of life that were to last through the arrival of Europeans. These effects were observed by the earliest European conquistadors and colonists in the 1500s – unbeknownst to them – long after the world had moved past the medieval era. Indeed, we base some of what we think happened in the medieval era on later Spanish observations. That said, some of these earliest European intruders make poor guides. They include Hernán Cortés, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado, Hernando de Soto, and Juan de Oñate. These men cared little about the native history and heritage that they were assaulting.

But other European explorers, especially the four men who survived the failed Pánfilo de Narváez expedition of 1528-1536, are quite good guides. These four men, the most notable of whom was Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, crisscrossed much of the same territory covered in this book, meeting colonial-era descendants of medieval peoples who had caused many of the historic changes that gave shape to the provinces that the Spaniards later called La Florida, Nueva Galicia, Nueva España, and the Yucatan.

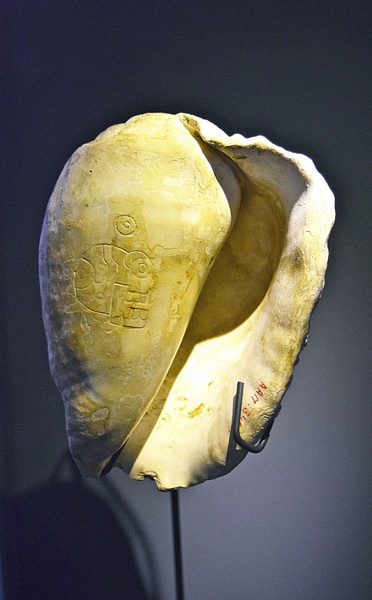

Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and his three companions, about to travel on their long journey west in 1535, had chided the Avavare people for their story of the Bad Thing, never considering that the story might have been the myth of an evil creator god – Tezcatlipoca or perhaps Xolotl – lord of the night winds or underworld, counterpart to a bearded beneficent creator god – Quetzalcoatl. Yet the Avavares and subsequent groups met by Cabeza de Vaca, Estevanico, Castillo, and Dorantes, considered the bearded foreigners to be the Children of the Sun – god-men who journeyed west. Cabeza de Vaca himself had carried seashells from group to group during his years as an itinerant middleman in the Texas interior. How often had he placed a shell up to his ear to wonder about the sounds of wind and crashing waves inside?

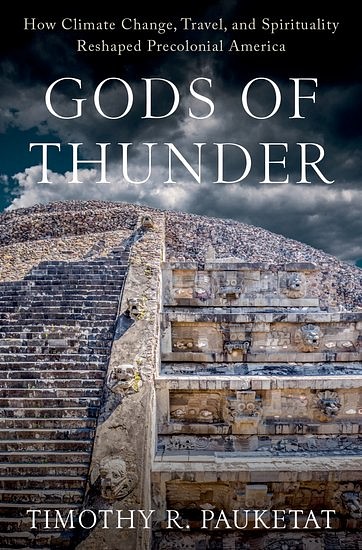

Shrines & Monuments

Now, consider the prominence and number of such shells, along with circular shrines, at a number of medieval-era archaeological places: Aztec, Cahokia, Chaco, Cherry Valley, Chichen Itza, Crenshaw, Cuicuilco, Calixtlahuaca, Emerald, George C. Davis, Ixtlan del Rio, Las Flores, Los Guachimontónes, Paquime, Tamtoc, Tenochtitlan, Trempealeau, and Tula Chico. Those shells meant something profound to descendants of peoples who lived through the Medieval Climate Anomaly. And those shells were often associated with wind, water, and circular temples, shrines, and pyramids that were frequently, in turn, paired with square platforms, buildings, or pyramids. They were connected to temples, sacred fires, and the realm of the dead by elevated causeways sometimes to or through water and occasionally with reference to a great water-bringer spirit – the Moon. And they were connected to or through upright poles and twisted ropes that reached up into the sky to the winds and clouds from whence lightning flashed.

Obviously, the various cultures north and south of the Pánuco developed on their own and were not all the same. Yet the peoples of these various regional traditions still communicated with each other, in one way or another, sharing certain understandings of the world around them, adopting the bundled practices of their neighbors near and far, and arriving in the modern era as distinctive peoples who nevertheless shared deeply enmeshed concepts and engrained practices. Circular shrines and monuments came to be central to the religious and urban complexes of the people in the volatile climatic regime of the Medieval Warm Period. Members of surrounding communities, one might presume, came to water shrines routinely to pray for rain or to be healed.

For farmers, there would have been very little more important in the world than healing the body, soul, community, and cosmos. These were the laborers who did the tilling and planting, the tending and harvesting, the cleaning and processing, and the storage and hauling of all the foodstuffs without which no city could have existed. Their fields were subject to floods and droughts and their bodies were subject to the aches and pains and illnesses and injuries of the sort that laborers are always disproportionately prone. They understood the plants they grew and the animals that might raid their fields. But as for how to be healed or how to control the weather – these were the jobs of shamans, priests, and elites who had access to the gods and who understood the cosmos.

Farmers needed them. They needed the blessings and healing power of the spirit world. They needed to get right with the gods. And so growers, pilgrims, and the curious from far away came into the sacred shrines and the cities that grew up about them. They carried in their ailing aunts and sick cousins, fathers, and mothers. They came into the shrines to pray to the gods, celebrate life, drink the healing waters, and be blessed inside the steamy dark chambers. In the process, the histories of Mesoamericans, Chichimecs, Caddos, Cahokians, Chacoans, and so many more to the north became intertwined.

None of these original indigenous cultures, with their overlapping philosophies and ontologies, developed in a vacuum. Rather, across North America, history swirled around medieval climatic shifts like the wind in a conch shell. If you listen carefully, you can still hear it. The atmosphere and the people were one, and so climate happened through people, and climate history was human history. It is the central lesson of America's medieval period and its gods of Thunder, from the Maya westward into Central Mexico, northward into the American Southwest and southern Plains, and, finally, up the Mississippi.