On 10 May 1796, in the later stages of the French Revolution (1789-1799), a group of leftwing agitators were arrested in Paris, charged with plotting to overthrow the French Directory. After a series of trials, two of them were guillotined and seven were deported, and the extremist Jacobins were once again kept from regaining power in France.

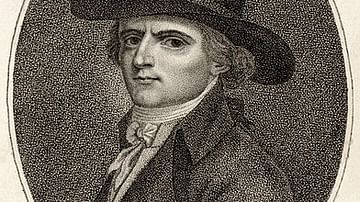

What could have been a minor footnote in the history of the French Revolution became something more when one of the surviving conspirators, the Italian-born Filippo Buonarotti, wrote a book detailing his recollections of this coup that never was. This book, entitled Buonarotti's History of Babeuf's Conspiracy for Equality (1828) was immensely successful, selling over 50,000 copies. It ensured the survival of the story of the Conspiracy of Equals, as well as that of its protagonist, an idealistic dreamer called Gracchus Babeuf (1760-1797).

Babeuf's conspiracy is famous, not for its impact on the French Revolution, which was minimal, but for its effect on later political thinkers and later revolutions. Babeuf is considered to be a proto-communist, whose ideas bridged the gap between French Jacobinism and the socialist movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. During Babeuf's lifetime, the terms 'communist' and 'anarchist' did not exist, yet both terms have been utilized by later scholars to describe Babeuf's ideas. He maintained that true equality could only be reached through the complete abolition of private property and that the state should distribute goods equally among the people. He believed that society needed to be restructured in such a way that no individual would desire riches or power over others. Babeuf and his failed conspiracy would later be praised by Karl Marx as "giving rise to the communist idea", and Babeuf himself would be called "the First Revolutionary Communist” (Furet, 179).

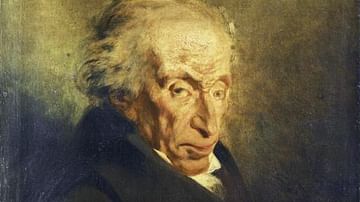

Babeuf's Early Life

François-Noël Babeuf was born on 23 November 1760 near the town of Saint-Quentin. His father was a retired soldier who married late in life but produced a large family, one that was perpetually in danger of slipping into poverty. As a child, Babeuf received some education from his father and attended a few years of primary school but was largely self-taught. His father died in 1780, and two years later, Babeuf married and started a family of his own. He was an affectionate husband and a loving father to his two children.

At the age of 18, Babeuf was apprenticed to a feudiste, a keeper of land records who specialized in feudal matters. In this capacity, Babeuf maintained records of seigneurial titles, estate management, and payments of feudal dues. As the years passed, this career led Babeuf to dwell on the ways land ownership led to imbalances of power as well as societal and economic inequality; as he later explained in an issue of his newspaper Le Tribun du Peuple, "It was in the dust of the seigneurial archives that I discovered the frightful secrets of the usurpations by the noble class" (Harkins, 434).

In 1786, he wrote an essay as part of a contest hosted by the Academy of Arras, in which he argued that society's individualistic economy failed to serve the common good and that France had to be restructured in a manner that fostered economic sharing. Around the same time, he began writing his pamphlet Permanent Survey, which he would scrap and rewrite in various forms before its publication in November 1789. In it, Babeuf advocates for the creation of a welfare state; his ideas are described by scholar James Harkins:

Society, for Babeuf, was a large family, and within that large family each member would contribute what he could according to his abilities, and each would be assured all that he needed. (438)

Babeuf's pamphlet also calls for equal access to education, on the basis that the absence of equal education lays the groundwork for oppression and tyranny. "In human society," Babeuf writes, "there must be no education at all or there must be equal access for everyone" (438). Babeuf also championed an equal redistribution of lands, similar to the Agrarian laws of the Roman Republic. Babeuf's personal heroes were the Gracchi brothers, the ancient Roman tribunes of the plebs who fought for similar land reforms and who were both assassinated for their efforts. Babeuf took steps to identify himself with the brothers, first through the name of his newspaper, Le Tribun du Peuple ("Tribune of the People") and then through his self-styled nickname, Gracchus.

Revolutionary Career

Babeuf was in Paris shortly after the French Revolution began in May 1789. On 4 August, the new National Assembly passed the August Decrees which abolished feudal dues and made Babeuf's feudiste occupation obsolete. Babeuf applauded the decision nonetheless, writing to his wife, "whatever it costs me, [feudal titles and privileges] can go to the devil" (Harkins, 434). He decided to try his hand at political journalism instead and travelled to the town of Roye in 1790. He wrote in defense of the poor and attacked the policies of the aristocrats in the National Assembly; his rhetoric earned him two brief prison stints in 1790.

In 1792, Babeuf became an administrator in the new revolutionary government for the General Council of the Somme Department. He served in this position until he was caught committing a forgery, forcing him to flee to Paris in February 1793 to avoid the punishment, which was a 20-year prison sentence. He did not stay a free man for long; that autumn, he was arrested for unrelated reasons and was left to languish in a Paris prison for six months, released only days after the fall of Maximilien Robespierre in July 1794. After his release, Babeuf initially wrote in praise of the conservative Thermidorians for bringing an end to the Terror and referred to Robespierre as "Maximilien the exterminator". This was an interesting reaction, completely at odds with the rest of his career, and perhaps reflected the general atmosphere of relief in Paris directly after the Terror, as the looming threat of the guillotine finally subsided.

But Babeuf soon returned to his old ways, founding Le Tribun du Peuple and attacking the bourgeois Thermidorians for their conservatism. He was arrested, again, in February 1795, and his newspapers were burned by the muscadins, a group of foppish thugs who were dedicated to rooting out leftwing extremism. Babeuf was transferred to a prison in Arras, where he became influenced by the other radical prisoners. Most significantly, he became acquainted with Filippo Buonarroti, an Italian national who had become a French citizen in 1793 and worked as a low-level administrator in the Robespierrist regime. Through his conversations with Buonarroti, Babeuf became further radicalized. He came to believe that property redistribution was not enough and that the concept of private property had to be completely abolished for true equality to be attained. It was around this core idea that the Conspiracy of Equals was born.

Tribune of the People

Babeuf, Buonarotti and their associates were released from prison in October 1795; the conservative royalists were becoming an increasing threat to the new French Directory, so the government decided to put leftwing agitators back on the streets as a counterbalance. Babeuf was released at the beginning of a harsh and dreadful winter, one that exacerbated the suffering of the poor and seemed to highlight the societal imbalances under the Directory. Babeuf resumed publishing Le Tribun du Peuple, voicing ideas that were more radical than even the most extreme Jacobin policies had been. "What is the French Revolution?" Babeuf wrote, "An open war between patricians and peasants, between rich and poor" (Doyle, 325). The Revolution, he argued, must not be allowed to end until it moved into its final stage, which was a class war. He believed that things had been heading in that direction under Robespierre but had been derailed when the bourgeois Thermidorians seized power and restored society to the way it had always been, with the rich at the top.

Babeuf's rhetoric found a large audience, particularly with Jacobins and sans-culottes who had been forced from the political stage. His paper was widely read throughout northern France and sold 2,000 copies within weeks of its first release. After the publication of the first two issues, the police were sent to arrest Babeuf, but he was hidden by sans-culotte supporters. By mid-February 1796, passionate readings of his paper were a common occurrence in the Pantheon Club, a place where radical leftists gathered after the closure of the Jacobin Club. After members of the Pantheon were heard denouncing the Directors as tyrants, the club was closed on 27 February by soldiers commanded by General Napoleon Bonaparte.

This did nothing to dissuade these neo-Jacobins, who began a secret organization which they named the Secret Directory of Public Safety. Members of this group included Babeuf and Buonarotti, as well as Jacobins who were better known to the public; Robert Lindet had been a member of the Committee of Public Safety during its heyday, and Marc-Guillaume Vadier had sat on the Committee of General Security during the Terror. One member, Sylvain Maréchal, was a follower of Babeuf who penned the Manifesto of Equals. It was from this manifesto that the society drew its charter: "we intend from now on to live and die as equals, just as we were born. We want true equality or death: that is what we must have" (Furet, 183). Before long, Babeuf, Buonarotti, and other members of the Secret Directory began to plot the Conspiracy of Equals, which had moved beyond simple idealism; the conspirators planned to take over the government.

Conspiracy of Equals

The goal of the conspirators was to overthrow the Directory, which they viewed as a corrupt government that was leading France backwards, back into the oppressive fog of despotism. Their conspiracy was based around the belief that private property should be abolished, and that all land should be communal; this necessitated a strong, authoritative central government to ensure things ran smoothly. The state would be responsible for the equal distribution of goods, which would be doled out according to each individual's needs.

The conspirators did not agree on everything; one hotly debated topic was Maréchal's statement: "Let the arts perish, if need be, as long as real equality remains". Yet for the most part, they rallied behind the Constitution of 1793, which had been written by the Jacobins but never implemented and had since become a banner for leftwing rebellion. They also promised to enact the Ventôse Decrees, another piece of Jacobin legislation that called for the redistribution of property. Some neo-Robespierrist conspirators also wanted to bring about a second Reign of Terror, to punish the Directory and its bourgeois leaders. Babeuf and his followers praised the butchery of the September Massacres, insisting something similar was needed to bring down the Directory.

The seven major conspirators who directed the plot included Babeuf, Buonarotti, and Maréchal, alongside Augustin-Alexandre Darthé, a radical agitator and friend of Babeuf's; Pierre-Antoine Antonelle, an ex-noble and a former president of the Jacobin Club; Felix Lepeletier; and Georges Grisel. The conspirators laid their plans throughout March and April of 1796. They planted agents in each of Paris' arrondissements to discreetly find support for their coup, and worked to subvert the new Police Legion, which had replaced the National Guards as the enforcers of law and order in Paris. The conspirators settled on 19 May as their day of action, which they referred to as the Day of the People. In preparation, they drafted an Insurrectionary Act, which proclaimed in the name of "Equality, Liberty, and the Common Happiness" that the people's sovereignty had been usurped by tyrannical bourgeois agents who the people needed to overthrow and bring to justice. However, it would not be long until these carefully laid plans became undone.

The Conspiracy Unravels

As it happened, the conspirators were not nearly as discreet as they thought. Paul Barras, one of the five Directors, had learned about the plot from his informants early on, yet decided to let events play out; Barras, a shrewd politician, was happy to keep a leftwing threat to check the growing influence of royalism. One of Barras' colleagues, however, was not content with leaving things be. Lazare Carnot was a former military officer now serving alongside Barras as a Director. Of the 'Twelve Who Ruled', the men who sat on the Committee of Public Safety during the Reign of Terror, Carnot was the only one who retained executive power. Although he had once shared power with Robespierre, the two never got along, and Carnot was eager to distance himself from Jacobin extremism.

Carnot learned of the conspiracy from one of the conspirators themselves; Georges Grisel sold the plan out in exchange for money. Carnot believed this was the perfect chance for him to wipe the Jacobin stain from his reputation and began to prepare to have the conspirators arrested. Meanwhile, on 28 April, units of the Police Legion mutinied. If the conspirators had seized on this opportunity to initiate their coup, they could have made use of the momentum and the confusion; instead, they decided to wait for the designated date of 19 May. In doing so, they lost their chance. The police mutiny was violently put down with 17 executions. Not long after, on 10 May, Babeuf and Buonarotti were arrested on Carnot's orders. Over the following days, 128 others were arrested in connection to the conspiracy across France, including Lindet, Vadier, and Jean-Baptiste Drouet, a member of the Directory who had been the postmaster that recognized King Louis XVI during the Flight to Varennes. During the arrests, Carnot's men seized the list of subscribers to Babeuf's papers; any high-ranking official whose name was listed was kicked out of his office.

Babeuf, Buonarotti, and the others were initially kept in the Tower of the Temple, the same prison that had once held King Louis XVI of France. While the conspirators languished in prison, the Jacobins of Paris were not ready to abandon their hopes of seizing power. There were 10,000 French soldiers encamped at Grenelle, who, according to rumor, were disgruntled, underpaid, and fed up with the Directory. On 9 September 1796, several hundred Jacobins began a march toward Grenelle, hoping to incite the soldiers to rebellion. But the Jacobins were unaware that the Directory had been tipped off; when they came within sight of the army camp they were met not by sympathetic soldiers, but with steel. The soldiers charged them, swords drawn, and they cut 20 Jacobins to pieces before scattering the rest. 30 of the leaders were arrested and executed. No further attempts were made to act on the Conspiracy of Equals.

Trials, Executions, & Legacy

In February 1797, Babeuf and his co-conspirators were transferred to Vendôme in iron cages to stand trial. Of the 128 men who had been arrested in connection to the conspiracy, 65 were tried; of those, 56 were acquitted. Babeuf had played a significant role in the conspiracy but had never been its leader. But for political reasons, he received the lion's share of the blame and was sentenced to death on 26 May 1797. Upon hearing the verdict, he attempted to commit suicide and stabbed himself multiple times in the courtroom. None of the wounds were fatal, and he was guillotined the next day without appeal. Another conspirator, Darthé, was also guillotined, while Buonarroti and six others were sentenced to deportation. None of the others were punished.

For the next 30 years, Babeuf's conspiracy, as the event became known, was remembered as nothing more than a minor footnote in the history of the French Revolution. But in 1828, Buonarotti wrote his History of Babeuf's Conspiracy for Equality. In it, Buonarotti recounts his memories of the conspiracy and relays the main tenets of Babeuf's ideas. This gave rise to Babouvism, which acted as a bridge between Jacobinism and later communism. The book was written at great personal risk to Buonarotti, who had to use an alias, but was successful, selling 50,000 copies. Through Buonarotti's efforts, the Conspiracy of Equals served as an inspiration to later political thinkers; Friedrich Engels and Karl Marx referred to the conspiracy as the "first appearance of a truly active communist party," and Leon Trotsky regarded Babeuf as a founder of the communist legacy.

Babeuf's conspiracy, therefore, would have a lasting effect on history, even though the initial coup never even got off the ground. Even amongst the conspirators, there was a consensus that it was impractical to expect such a socialist utopia to exist in their lifetimes. In his Manifesto of Equals, Maréchal writes: "The French Revolution is only the forerunner of another, far greater, more solemn revolution, which will be the last" (Furet, 184). It was a statement that seems to herald the rise of Bolshevism and the Russian Revolution in the early 20th century.