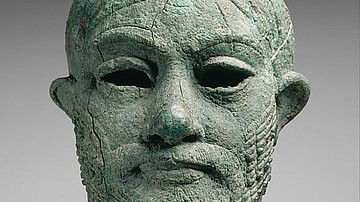

The Dialogue of Pessimism (c. 1000 BCE) is a Babylonian poem featuring a master and his slave in ten exchanges during which the master proposes an action, and the slave gives reasons for and against its pursuit. The piece has been interpreted as an existential statement, satire, a theodicy, and social commentary.

The work is best known from the existential interpretation advocating suicide as the only response to a meaningless world in which there is no good reason to pursue one course over another. It is catalogued as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian wisdom literature and was copied as part of the curriculum of the scribal schools. It is clear the piece served as an educational text, but whether students took its content and theme seriously is unknown. It is possible the piece was simply a comedic dialogue making fun of popular proverbs and their conventional use in the classroom in the same way the poems Schooldays and A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe satirize the Mesopotamian educational system.

The poem's title is a modern-day designation (given by W. G. Lambert), and the original, if it ever had one, is lost. The piece develops through ten exchanges on the futility of action since anything one considers worth doing can be countered by equally good reasons not to:

- On Visiting the Palace

- On Dining

- On Hunting

- On Marriage

- On Leading a Revolution

- On Sex

- On Religious Sacrifice

- On Investing

- On Philanthropy

- On Public Service

The piece ends with a final stanza in which the master concludes that the only reasonable response to life is to seek death, but before taking that step, he will send his slave on ahead of him. The slave, who appears the wiser of the two, has the last line on how his master would not be able to survive three days without him. Based on this, and the slave's responses throughout, the poem can also be understood as a satire on social class, featuring the "wise servant" and "foolish master", a popular motif in ancient and modern works of literature.

Origin & Purpose

The poem may have originally been a Sumerian composition performed as part of a student's final exam period in the edubba ("House of Tablets"), the Sumerian scribal school. The edubba was established in Sumer by the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) to train scribes in ancient Mesopotamia, and its curriculum focused on copying, memorizing, and reciting various texts. Students progressed from copying simple lists and hymns to more difficult written works but also committed oral works to writing.

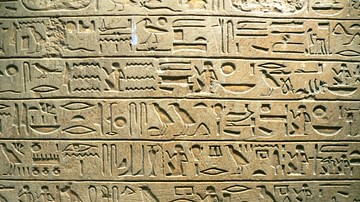

Prior to the invention of cuneiform script c. 3500 BCE, stories and poems existed only as an oral tradition. One of the earliest jobs of scribes in ancient Mesopotamia would have been preserving these works in written form, as scholar Jeremy Black notes:

Although a literary composition about oral transmission may seem to be paradoxical or perverse, it is simply a reflection of the scribes' everyday reality: patterns of preservation of tablets suggests strongly that our manuscript sources are not the traces of a copied literary tradition but one of telling, listening, and memorization. Ironically, many of the tablets preserving the world's oldest literary tradition are ephemera: they were produced as part of the memorization process and were never intended to last. (275)

Clay writing tablets used for student exercises, in fact, were frequently recycled by instructors who would drop them into tubs of water to soften, be erased, and reformed as new ones. Texts of established written works were preserved, however, for future students to memorize and recite and, among these, was the Dialogue of Pessimism. The extant copies are from Assyria and Babylonia, written in Akkadian script, but as with many other such works, it is most likely much older and, as noted, of Sumerian origin.

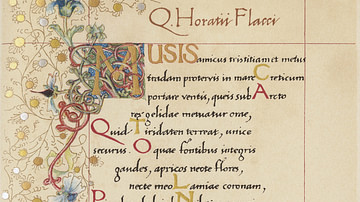

Its purpose would have been to entertain while also providing students with an interesting piece to practice from, and although it is labeled as 'wisdom literature' in the present day, it may not have been regarded as such in ancient Mesopotamia. The designation 'wisdom literature' itself is a modern construct applied by biblical scholars to the books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Job long before works of Mesopotamian literature were discovered in the mid-19th century. Once cuneiform was deciphered, works such as The Instructions of Shuruppag (c. 2600-2000 BCE), Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi (c. 1700 BCE), and others similar to or thought to have influenced the later biblical books were given that same label.

Interpretations of the Text

It is possible, however, that the early scribes did take the Dialogue of Pessimism as seriously as other works now grouped together as 'wisdom literature.' The British scholar and archaeologist Wilfred G. Lambert notes:

The Dialogue of Pessimism, if it is to be taken seriously, takes the final step, declaring all life to be futile, and suicide to be the only good. (17)

Understood as a serious commentary on the futility of existence, the work can be compared to The Dispute Between a Man and his Ba (soul) from the period of Egypt's Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) which, like the Dialogue of Pessimism, is thought to have influenced the Book of Ecclesiastes, certain biblical proverbs, and part of the Book of Lamentations. In the Egyptian work, a man discusses life's difficulties with his soul, asking why he should continue living when there seems no point to it. The soul tells him he should just enjoy what life has to offer and focus on the good rather than the bad.

There is some question as to whether the work was intended to be taken seriously at all, however. Scholars including Jean Bottero and A. Leo Oppenheim argue against the seriousness of the piece, noting its clear absurdity and comedic tone. Oppenheim writes:

[The Dialogue of Pessimism] presents a master and his servant engaged in an obviously comic dialogue. The master gives order after order, to which the servant responds with a number of proverbial sayings that are meant to prove the wisdom of the master's wish. When the master abruptly changes his mind and revokes each order, the servant has no difficulty in finding other proverbs to support the latest orders. The purpose – other than to amuse the reader – seems to have been a demonstration that the wisdom of proverbs is no reliable guide. To enliven the presentation, the servant is shown as much brighter than his master, whom he patently attempts to please and to appease. (273-274)

Scholars who claim the work is a satire on proverbial wisdom note how the slave consistently responds with conventional maxims – "Repeated dining relaxes the mind" and "The man who loves a woman forgets sorrow and fear" as well as the many others – and also references literary works such as The Epic of Gilgamesh (line 54) and even quotes a proverb (line 57). Among the varied interpretations of the poem, these two – existential statement or satire on proverbial wisdom – are the most common.

Text

The following passage is taken from Babylonian Wisdom Literature, translated by W. G. Lambert. Line numbers given here differ from Lambert's for the purpose of clarity. Ellipses indicate missing words or sentences. The text is one of the more complete extant, only fragmented between lines 16-24, with both the beginning and conclusion intact.

1."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

2. "Quickly, fetch me the chariot and hitch it up so that I can drive to the palace."

3. "Drive, sir, drive. It will be to your advantage. When he will see you, the king will give you honor."

4. "No, slave, I will by no means drive to the palace."

5. "Do not drive, sir, do not drive. When he will see you, the king may send you ... and will make you take a route that you do not know; he will make you suffer agony day and night."

6. "Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

7. "Quickly, fetch me water for my hands, and give it to me so that I can dine."

8. "Dine, sir, dine. Repeated dining relaxes the mind ... his god's repast; Shamash accompanies washed hands."

9. "No, slave, I will certainly not dine."

10. "Do not dine, sir, do not dine. Hunger and eating, thirst and drinking, come upon a man." (i.e. you should just eat and drink when you want to)

11. "Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

12. "Quickly, fetch me the chariot and hitch it up so that I can drive to the open country [to hunt]."

13. "Drive, sir, drive. A hunter gets his belly filled. The hunting dogs will break the [prey's] bones, the hunter's falcon will settle down, and the fleeting wild ass ..."

14. "No, slave, I will by no means drive to the open country."

15. "Do not drive, sir, do not drive. The hunter's luck changes; the hunting dog's teeth will get broken, the home of the hunter's falcon is in ... wall, and the fleeting wild ass has the uplands for its lair."

(the next stanza combines marriage and litigation as the tablet is fragmented with several lines missing)

16. "Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

17. "I am going to set up a home and have children."

18. "Have some, sir, have some. The man who sets up a home ... a door called 'The Snare' ... robust, two-thirds a weakling."

19. "... I will burn, go and return. I will give way to my prosecutor."

20. "So give way, sir, give way."

21. "So, so, I will make a home."

22. "Do not make a home. A man who follows this course breaks up his father's home ... Remain silent, sir, remain silent."

23. "No, slave, I will not remain silent."

24. "Do not stay silent, sir, do not stay silent ... unless you open your mouth ... Your prosecutors will be savage to you ... "

25."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

26."I will lead a revolution."

27."So lead, sir, lead. Unless you lead a revolution, where will your clothes come from? Who will enable you to fill your belly?"

28."No, slave, I will by no means lead a revolution."

29."The man who leads a revolution is either killed, or flayed, or has his eyes put out, or is arrested, or is thrown into jail."

30."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

31."I am going to love a woman."

32."So love, sir, love. The man who loves a woman forgets sorrow and fear."

33."No, slave, I will by no means love a woman."

34."Do not love, sir, do not love. Woman is a pitfall – a pitfall, a hole, a ditch, Woman is a sharp iron dagger that cuts a man's throat."

35."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

36."Quickly, fetch me water for my hands and give it to me so that I can sacrifice to my god."

37."Sacrifice, sir, sacrifice. The man who sacrifices to his god is satisfied with the bargain; he is making loan upon loan."

38."No, slave, I will by no means sacrifice to my god."

39."Do not sacrifice, sir, do not sacrifice. You can teach your god to run after you like a dog, whether he asks of you `rites' or `Do you not consult your god?' or anything else."

40."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

41."I am going to make loans as a creditor."

42."So make loans, sir, make loans. The man who makes loans as a creditor – his grain remains his grain, while his interest is enormous."

43."No, slave, I will by no means make loans as a creditor."

44."Do not make loans, sir, do not make loans. Making loans is like loving a woman; getting them back is like having children…They will eat your grain, curse you without ceasing, and deprive you of the interest on your grain."

45."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

46."I will loan food to my country."

47."So loan, sir, loan. The man who loans food to his country, his grain is enormous."

48."No, slave, I will not loan food to my country."

49."Do not loan, sir, do not loan. They will eat your grain, diminish the interest on your grain, and curse you without ceasing in addition."

50."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

51."I will perform a public benefit for my country."

52."So perform, sir, perform. The man who performs a public benefit for his country, his deeds are placed in the ring of Marduk."

53."No, slave, I will by no means perform a public benefit for my country."

54."Do not perform, sir, do not perform. Go up on to the ancient ruin heaps and walk about; see the skulls of high and low. Which is the malefactor, and which is the benefactor?"

55."Slave, listen to me." "Here I am, sir, here I am."

56."What, then, is good?"

57."To have my neck broken and your neck broken and to be thrown into the river is good. `Who is so tall as to ascend to the heavens? Who is so broad as to compass the underworld?'"

58."No, slave, I will kill you and send you first."

59."And my master would certainly not outlive me by even three days."

Conclusion

The Dialogue of Pessimism, in addition to the above-mentioned interpretations, is also understood by some scholars as a theodicy – a vindication of a god against claims of unjust suffering by humans – exemplified by works such as the Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi and the Book of Job. This interpretation seems untenable, however, as the divine is referenced only twice (lines 35-39 and line 52). The first time it is suggested that humans can make the gods their servants by neglecting sacrificial offerings and the second time is simply how the divine (Marduk) approves of public service.

A fourth interpretation of the work, focusing on the stock characters of the "wise servant" and "foolish master", reads it as satire on social inequality. The master clearly has vast resources but lacks any insight on how best to use them, while his slave, who has nothing, can recognize not only the value of those resources but the possible consequences, pro and con, of utilizing them. Several proverbs and folktales from Mesopotamia deal with this same theme, often using animals as characters. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

Behind the Mesopotamian humor, of course, is a serious message about social injustice: how a poor peasant might not be able to afford a decent plot to work; how the talents of a worker might be taken advantage of by an unfeeling boss; and how the rich and powerful might lord it over the humble. Despite the legal codes of Ur-Nammu and Hammurabi, unlegislated (and perhaps unlegislatable) inequities still lurked between the lines – even as they still do today despite all our laws. (180)

The message of the poem may be as simple as the popular saying, "the wrong people have all the money" in referencing the wealthy who spend lavishly on whatever they please while others work their lives away for basic necessities. The slave has the last word in the piece, claiming that, without him, his master would not survive even three days; just as the more affluent in any society depend on those they consider beneath them to sustain their wealth and the luxury of choice in what they will or will not do.