The railways were perhaps the most visible element of the Industrial Revolution for many. Trains powered by steam engines carried goods and people faster than ever before and reached new destinations, connecting businesses to new markets. There were also unfortunate consequences such as the decline in traditional transport like canal boats and stagecoaches, and the impact on unspoilt countryside.

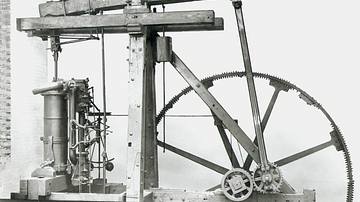

The Steam Engine

The steam engine was perhaps the most important invention of the Industrial Revolution and without it, fast-moving trains would not have been possible. In 1698, a steam-powered pump was invented by Thomas Savery (c. 1650-1715). In 1712, Thomas Newcomen (1664-1729) adjusted Savery's design and greatly increased the power. James Watt (1736-1819) worked on Newcomen's design, and by 1778, he had greatly reduced the fuel consumption of the steam engine. Engineers continued to improve the engine until it worked using a pressure high enough to create the power capable of moving large weights with a minimum amount of fuel. In 1801, Richard Trevithick (1771-1833) invented the first steam-powered vehicle. Trevithick's machine was pretty good, but his real problem was the poor condition of the roads at that time. The inventor solved the problem in 1803 by having his vehicle run on purpose-built tracks of its own. The idea of a steam-powered railway train was born.

Replacing the Old

The driving force behind the Industrial Revolution was commercial enterprise and the search for profit. Transportation was one area where a brand-new power source could really change how things were done. Traditionally, goods in larger quantities were transported across Britain by river and canal boats. Rivers were obviously limited to where they ran but a canal system was built to specifically connect large urban centres. Canal boats could transport goods safely and relatively cheaply, but the problem was the speed. Taking into consideration the necessity to go through lock systems where the terrain rose or fell, the average speed of a canal boat on its journey from one destination to another was around 4.8 km/h (3 mph). Not very impressive. It was usually quicker to transport goods from one continent to another than from one inland town to another. The land journey was the weak link. Another problem was that canals were very expensive to build. Investors and company owners saw that a cheaper but faster alternative to canals would reduce the time taken to reach markets for their goods and open up new markets if a network were built bigger and better than the existing canal system. A second area of potential was private travellers obliged to use horse-drawn stagecoaches, which were slow and uncomfortable. The railways, then, could serve two customer bases: freight companies and passengers.

The Stephensons & Rocket

The first move towards finding an alternative to canals and river boats was to use wheeled carriages running on iron rails with the carriages pulled by horses. This sort of hybrid technology worked well sometimes (for example, on the short Surrey Iron Railway to Croydon) but was hardly the great leap forward big business was looking for. Trevithick's engine on rails showed the way. Next up came George Stephenson (1781-1848), who had his own company in Newcastle that specialised in building railway trains to transport coal over short distances at coal mines. Stephenson designed the Locomotion 1 train engine. This locomotive was powerful enough to pull carriages, and it transported the first steam railway passengers from Stockton to Darlington in the northeast of England in 1825. This line was a success and showed what might be achieved elsewhere on a grander scale as the age of steam took off.

A new railway line was built from Liverpool to Manchester in 1829, the world's first inter-city railway. The problem was the directors of the Liverpool & Manchester Railway Company (L&MR) did not have any locomotives for their line. The directors organised a competition, inviting inventors to the Rainhill Trials where their machines would be extensively tested for speed, reliability, ability to pull carriages, and total fuel and water consumption. The winning locomotive was Rocket, designed by George Stephenson's son Robert Stephenson (1803-1859). Stephenson's Rocket was essentially the sum of all the inventions up to that point regarding steam engines. Running with flanged wheels on smooth cast iron rails, Rocket's top speed was at least 48 km/h (30 mph), not great today but astounding for the people of the mid-19th century and something that had never been seen or experienced before. The L&MR directors immediately commissioned Stephenson to make four more Rocket locomotives, and their train line was opened on 15 September 1830. The line was a roaring success (despite the death of William Huskisson MP, run over by a locomotive on the very first day). Soon the line was carrying 1,200 passengers every day. Goods were also carried on the line where a single train could carry 20 times the cargo of a canal boat and reach its destination eight times faster. It was now merely a question of time before all of Britain had access to the railways.

Railway Mania

The railway lines spread quickly. In 1838, Birmingham was connected to London, and in 1841, passengers could take the train from the capital to Bristol. The latter line was designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) and run by the innovative Great Western Railway which built Paddington Station in London. The line was another success and was later extended into Devon and Cornwall. The iron tracks spread so quickly across Britain, the phenomena became known as 'railway mania'. By 1845, there was a line from Manchester to London, which took eight hours of travel (a passenger on the old stagecoaches would have shaken and shivered for 80 hours to make the same journey). From 1848, passengers could travel from London to Glasgow in 12 hours as trains reached speeds of 80 km/h (50 mph). Newspapers boasted that fortunate businessmen could have breakfast in London, a business lunch in Birmingham, and be back again to dine in London, all in the same day. The trunk lines between major cities began to be connected by secondary lines to smaller cities and towns as the rail network became much denser across Britain. By 1870, there were over 24,000 kilometres (15,000 miles) of rail lines.

It was not all smooth running. Train lines required some major feats of engineering such as viaducts, tunnels, bridges, and the draining of marshlands. Early steam engines lacked the power to pull carriages up very steep inclines and so had to be helped by larger rope-hauling steam machines set by the track. The invention of mass-produced steel by Henry Bessemer (1813-1898) in 1856 allowed for rails that could carry heavier, more powerful, and faster trains, which meant these static engine assistants were no longer required.

As with many new technologies, parallel development meant that sometimes there were compatibility problems across regions. The Stephenson trains ran on rails with a gauge of 1.4 metres (4 ft 8.5 in). Brunel's trains ran on rails with a gauge of 2.1 metres (7 ft), better for the stability of the train when carrying heavy goods but more expensive to build. The 'gauge wars', as these technical differences became known, meant some stretches of line had three parallel rails so that both types of train could run on them. Otherwise, where this was not the case, passengers often had to disembark, luggage and all, and join a different train that could run on the alternative gauge tracks. For goods trains this was even more impractical creating delays reminiscent of a canal boat going through a series of locks, the very system trains were meant to replace. A Royal Commission was charged with investigating this damaging impediment to the progress of the railways, and eventually, the great gauge battle was settled in favour of the narrower gauge. Consequently, the railways were made uniform by an 1846 Act of Parliament.

There were other problems besides engineering ones. Some town councils and large estate owners blocked the building of train lines in their domains (Northampton and Stamford, for example), but this only meant that in the longer term, these places were left behind economically while a nearby rival town that had accepted the railways flourished. Many of those towns that had not accepted a main line were, in any case, eventually obliged to pressure the relevant railway company to build a branch line linking them to the rail network. In short, for good or bad, there was no going back to the old ways. By 1871, trains across Britain were carrying over 300 million passengers and over 150 million tonnes of goods each year.

A Global Phenomenon

The idea of railways spread around the world, and then innovations came back to Britain to improve the railways there. In the United States, the first working railroad was completed in 1833 and connected New York to Philadelphia. The immense size of the USA had always been a problem, but now the railroads forged ahead, meaning that the huge resources such a great land produced could be, at last, fully exploited.

The first railway line in Continental Europe was completed in Belgium in 1835 to connect Brussels and Malines. The American engineer George Pullman (1831-1897) created the first sleeping cars in 1856 which used seat cushions which could be moved to create a sleeping berth. In 1868, the New Yorker George Westinghouse (1846-1914) developed a trio of successful inventions: the air brake, which used compressed air to quickly stop the wheels turning, a signal system, and the frog that meant a train could cross intersecting tracks. By 1870, Canada, Australia, India, and most of Europe had joined in the railway mania. Trains were becoming ever more ambitious in the distance and comfort they promised their passengers. The luxurious Orient Express ran from 1883 and connected Paris to Constantinople (Istanbul). The railroads became a symbol of the modern age, but not everyone benefitted or liked this new and faster world.

Impact of the Railways

At first, many train companies bought out the canals in their area so that they could control the competition. Many canals were kept running, but eventually, they simply could not compete with the trains, and the canal system fell into neglect. The other direct competitor of trains, the stagecoaches, fared no better. Stagecoach and mail coach operators, coaching inns dotted along the roads, turnpike roads (private roads which charged a passage toll), and those who bred and cared for horses all suffered badly as trains took their business. As an example of the decline, before the railways, 29 stagecoaches travelled from Manchester to Liverpool every day, but after the arrival of the trains, there were only two providing this service.

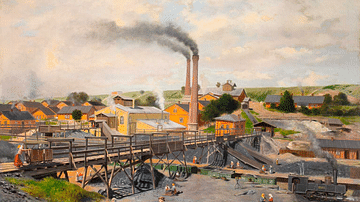

People had to leave their homes and family land to make way for the metal tracks being laid everywhere. Private Acts of Parliament were passed for each line, and these gave the railway companies the right to buy the land they needed and evict anyone that blocked the building plans. People worried that passing trains scared livestock and disrupted forest hunting. Finally, air pollution, both from the trains themselves and the coal mines that fed them, noticeably worsened.

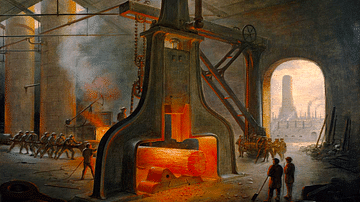

There were many positives to the new railways besides cheaper and faster transportation of people and goods. Steam trains needed huge amounts of coal, which resulted in more mines and more jobs (far more than were lost in other areas). The steel and iron needed for the locomotives, carriages, rails, bridges, and tunnels caused a boom in those industries. Britain produced annually just 2.5 million tonnes of coal in 1700, but by 1900, this figure had rocketed to 224 million tonnes. The railways created vast construction projects which employed tens of thousands of labourers. The railway companies also needed engineers, drivers, stationmasters, ticket collectors, and in the stations were porters, lavatory attendants, and staff for refreshment rooms as millions of first-, second-, and third-class passengers were now using the train services regularly.

Factory owners could now build their factories anywhere, no longer restricted to sites close to waterways or coal fields. Outer suburbs developed in cities as workers commuted by train to their jobs in city centres. The cost of raw materials decreased and business practices changed. Manufacturers no longer had to keep a large inventory of goods but could move them on as soon as ready. The cost savings of reduced warehouses meant more money and factory space could be devoted to manufacturing, further bringing down costs and creating more jobs.

As the trains connected more and more towns, people could travel to places they had never or very seldom been to. Seaside resorts, in particular, boomed thanks to cheap weekend excursion tickets and factory workers forming clubs which were paid into regularly to save up for a works outing. Places like Blackpool, Scarborough, and Brighton became familiar names around the country, conjuring up images of fun and holidays by the sea. The same worked for schools as children could now travel to prestigious private institutions far from home.

The ever-greater efficiency of trains meant goods could be transported more cheaply, and so they became more affordable to more people. Businesses could now sell their products to new markets. Products like fresh fish were available in inland areas for the first time. This resulted in a boom in advertising as the physical distance between businesses and their customers grew. Train stations became mass gathering places of humanity and so were perfect locations in which to advertise.

Trains carried mail, which became cheaper than ever after Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882) created the Universal Penny Post in 1840 where senders used the famous Penny Black postage stamps. Trains allowed someone in Scotland to read the morning newspaper issued that day in London. The whole world seemed to have shrunk, and people, goods, and information whizzed from one place to another at a pace never before imagined. The celebrated author Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) was not exaggerating when he noted that the railways had brought more change than any other development since the Norman conquest of England in 1066.