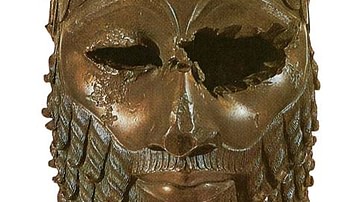

Sargon and Ur-Zababa is a Sumerian poem, date of composition unknown, relating the rise to power of Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE), founder of the Akkadian Empire. The work is classified as a Mesopotamian folktale, relying on motifs such as the dream vision and the scheming king, but it may have been regarded as history in its time.

The poem might have been composed during the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE) when several other works concerning Sargon were written or committed to writing from oral tradition. The kings of the Ur III Period – especially Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) and Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE) – associated themselves closely with the Akkadian kings, specifically with Sargon and his grandson Naram-Sin (r. 2261-2224 BCE). This claim regarding dating is speculative, however, as no certain date has been given for the work.

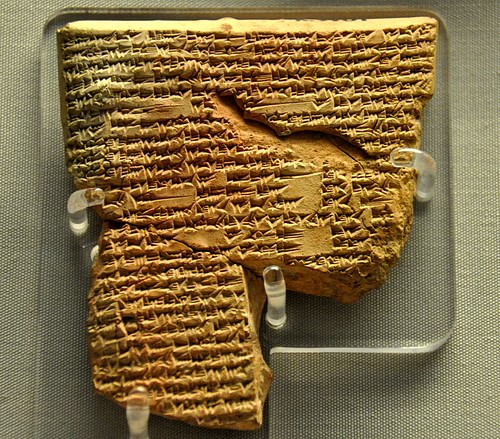

The popularity of the poem is attested by the copies found in the ruins of ancient Mesopotamian cities dating to around the 7th century BCE when the region was controlled by the Assyrians. This clearly suggests tales concerning Sargon – and Naram-Sin – still resonated with audiences over a thousand years after their reigns. The work is unfortunately poorly preserved and exists only in fragments, as noted by scholar Jeremy Black:

Sargon and Ur-Zababa has been tentatively reconstructed from two manuscripts, a fragment from Uruk (Segments A and C) and a more complete tablet from Nippur (Segment B). While the events that concern the poem occur primarily in the north of Babylonia, the tablets on which it is recorded come from the south. (40-41)

The locations of the fragments also attest to the popularity of the piece and further suggest its origin in the Ur III Period when scribal schools – which used such texts as part of the curriculum – proliferated throughout Sumer under the reign of Shulgi of Ur.

The piece is sometimes known as The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, but that title is far more commonly applied to another work relating Sargon's birth, youth, and conquest of the Sumerian city-states. Sargon and Ur-Zababa, on the other hand, focuses on a specific period in the future king's life when, in accordance with the will of the gods, he is delivered from the schemes of the king Ur-Zababa and, it is suggested, replaces him.

Sargon's Legend & Reign

Almost nothing is known of Sargon's life, and what is known comes from texts regarded today as belonging to the genre of Mesopotamian naru literature – the world's first historical fiction – which casts a famous figure (usually a king) as the main character in a fictional tale. The Legend of Sargon of Akkad is among the best-known pieces from this genre and presents Sargon as the illegitimate son of a priestess, set adrift on the Euphrates River, who is taken in and raised by a gardener, eventually becoming king of Akkad and Lord of Sumer. Black comments:

Little is known about Sargon's origins. According to a much later Akkadian legend [The Legend of Sargon of Akkad], he was the illicit child of a priestess who, much in the manner of Moses in the Bible, was placed in a wicker basket and cast adrift upon the water, to be rescued and raised by a gardener. Such folktale motifs were also incorporated into Sumerian literature, including, in Sargon and Ur-Zababa, instances of dreams which foretell the future. This folktale motif is embedded within the narrative which has theological concerns, dreams being regarded as messages predicting a divinely ordained future which man alone cannot resist. (40)

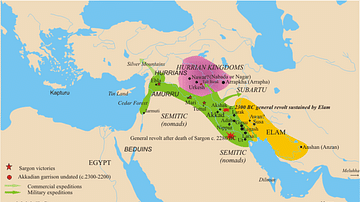

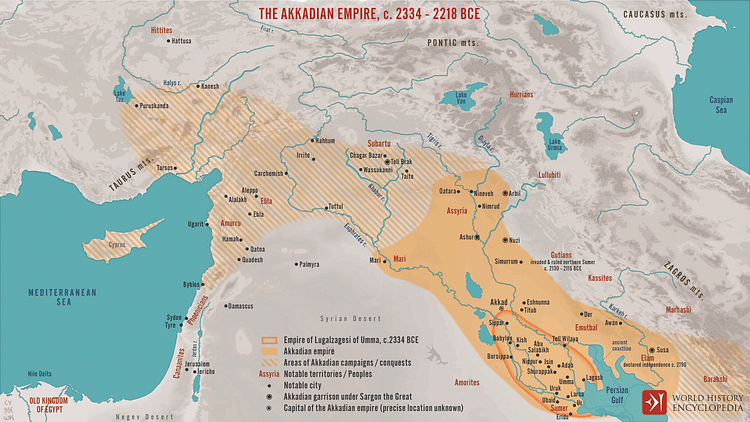

Sargon, according to the poem, is favored by the gods who have him raised by the gardener, Akki, to become cupbearer to the king Ur-Zababa of Kish, whose reign they have decreed must end. Historically, at this time, Sumer was largely under the control of Lugalzagesi of Umma (r. c. 2358-2334 BCE), who was conquering the city-states and building an empire. In the poem, Ur-Zababa, growing suspicious of Sargon after an ill-omened dream, sends his cupbearer to the king with instructions to kill him. Lugalzagesi instead befriends Sargon, who turns on his former master, and together they conquer Kish.

Sargon then broke his pact with Lugalzagesi, defeated him in battle, and imprisoned him. After creating a professionally trained army and consolidating his power, Sargon revolutionized Mesopotamian warfare in leading his army on a campaign of conquest throughout the entire region, eventually establishing the Akkadian Empire (2334-2218 BCE), which would become legendary down through the time of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 BCE). Scholar Paul Kriwaczek notes:

For at least 1,500 years after his death, Sargon the Great ... was regarded as a semi-sacred figure, the patron saint of all subsequent empires in the Mesopotamian realm. Indeed, two much later kings, one who ruled Assyria around 1900 BCE and the other at the end of the eighth century BCE, adopted his official name, or rather title, Sargon [which means] "Legitimate King", as if to steal a bit of his thunder for themselves. (111)

Kriwaczek is referring to the Assyrian kings Sargon I (r. c. 1920-1881 BCE), about whom little is known, and Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE) who became as legendary as Sargon of Akkad, especially after his victory over the kingdom of Urartu in 714 BCE. The popularity of Sargon of Akkad among the Assyrians is attested, not only by these kings, but by the copies of works relating to him found in the ruins of the Library of Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE) at Nineveh and, as noted, elsewhere.

Summary & Commentary

The poem relates how Sargon was chosen by the gods to fulfill his destiny by overthrowing Ur-Zababa even though, as the work begins, Sargon himself seems content as Ur-Zababa's servant, oblivious to the gods' plans. In section A, the dramatic scene is set describing the glorious city of Kish under the rule of Ur-Zababa. The king has raised the city from a ruin ("like a haunted town") to a prosperous and thriving agricultural and urban center.

The great gods An (Anu) and Enlil, however, have decided that Ur-Zababa's time is at an end. Sargon is introduced toward the conclusion of this segment, and his father's name is given as La'ibum – a name given nowhere else (in The Legend of Sargon of Akkad, he claims to have never known his father) – and it seems the poem originally described Sargon in full, but the fragment breaks off and the rest is lost.

Segment B, as Black notes, is the most complete and opens with the dream of Ur-Zababa, which, though the details are not given, frightens him and is understood as an omen of his impending fall from grace. The narrator notes how the goddess Inanna has chosen to side with Sargon who also has a dream in which Inanna drowns Ur-Zababa in a river of blood.

Ur-Zababa interprets Sargon's dream to mean Inanna wants Sargon killed, not himself, and devises a scheme by which he will send Sargon to his head smith at the temple where statues are cast, and the smith will throw Sargon into one of the casting molds. Sargon, suspecting nothing, goes on the errand for the king but is stopped at the temple gate by Inanna who tells him he cannot enter because he is polluted by blood. This would normally mean he had killed or seriously injured someone, but, as Black notes, in this case, may be understood as pollution from his dream of the river of blood.

Sargon completes his errand, still seemingly oblivious to Ur-Zababa's plans or those of the gods, and returns to the king, which frightens Ur-Zababa even more as it begins to dawn on him that the gods favor Sargon. He then sends Sargon on a mission to Lugalzagesi, allegedly offering a peace treaty but actually bearing a tablet telling the king to kill the messenger.

Section C, badly damaged, suggests Sargon has an affair with Lugalzagesi's wife, but for unknown reasons, the king ignores this (or never learns of it) and Ur-Zababa's request and spares the young man. The last part of the poem seems to deal with Lugalzagesi's realization that Sargon will also replace him, though this is speculative as most of the lines have been lost. Historically, however, it is established, as noted above, that Sargon did in fact defeat Lugalzagesi as one of the first steps in establishing his empire.

Text

The following is taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al. Ellipses indicate missing lines or words while question marks suggest an alternate translation for a word.

A.1-9: To ... the sanctuary like a cargo-ship; to ... its great furnaces; to see that its canals…waters of joy, to see that the hoes till the arable tracts and that ... the fields; to turn the house of Kish, which was like a haunted town, into a living settlement again – its king, shepherd Ur-Zababa, rose like Utu over the house of Kish. An and Enlil, however, authoritatively (?) decided (?) by their holy command to alter his term of reigning and to remove the prosperity of the palace.

A.10-13: Then Sargon – his city was the city of ... his father was La'ibum, his mother ... Sargon ... with happy heart. Since he was born ... (unknown number of lines missing).

B.1-7: One day, after the evening had arrived and Sargon had brought the regular deliveries to the palace, Ur-Zababa was sleeping (and dreaming) in the holy bedchamber, his holy residence. He realized what the dream was about, but did not put it into words, did not discuss it with anyone. After Sargon had received the regular deliveries for the palace, Ur-Zababa appointed him cupbearer, putting him in charge of the drinks cupboard. Holy Inanna did not cease to stand by him.

B.8-11: After five or ten days had passed, king Ur-Zababa ... and became frightened in his residence. Like a lion he urinated, sprinkling his legs, and the urine contained blood and pus. He was troubled, he was afraid like a fish floundering in brackish water.

B.12-19: It was then that the cupbearer of Ezina's wine-house, Sargon, lay down not to sleep, but lay down to dream. In the dream, holy Inanna drowned Ur-Zababa in a river of blood. The sleeping Sargon groaned and gnawed the ground. When king Ur-Zababa heard about this groaning, he was brought into the king's holy presence, Sargon was brought into the presence of Ur-Zababa (who said) "Cupbearer, was a dream revealed to you in the night?"

B.20-24: Sargon answered his king: "My king, this is my dream, which I will tell you about: There was a young woman, who was a high as the heavens and as broad as the earth. She was firmly set as the base of a wall. For me, she drowned you in a great river, a river of blood."

B.25-34: Ur-Zababa chewed his lips, he became seriously afraid. He spoke to ..., his chancellor: "My royal sister, Inanna, is going to change (?) my finger into a ... of blood; she will drown Sargon, the cupbearer, in the great river. Belis-tikal, chief smith, man of my choosing, who can write tablets, I will give you orders, let my orders be carried out! Let my advice be followed! Now then, when the cupbearer has delivered my bronze hand-mirror (?) to you, in the E-sikil, the fated house, throw them (the mirror and Sargon) into the mould like statues."

B.35-38: Belis-tikal heeded his king's words and prepared the moulds in the E-sikil, the fated house. The king spoke to Sargon: "Go and deliver my bronze hand-mirror (?) to the chief smith!"

B.38a-42: Sargon left the palace of Ur-Zababa. Holy Inanna, however, did not cease to stand at his right-hand side, and before he had come within five or ten nindan [19 feet/6m] of the E-sikil, the fated house, holy Inanna turned around toward him and blocked his way, (saying): "The E-sikil is a holy house! No one polluted with blood should enter it!"

B.43-45: Thus, he met the chief smith of the king only at the gate of the fated house. After he delivered the king's bronze hand-mirror (?) to the chief smith, Belis-tikal, the chief smith ... and threw it into the mould like statues.

B.46-52: After five or ten days had passed, Sargon came into the presence of Ur-Zababa, his king; he came into the palace, firmly founded like a great mountain. King Ur-Zababa ... and became frightened in his residence. He realized what it was about, but did not put it into words, did not discuss it with anyone. Ur-Zababa became frightened in the bedchamber, his holy residence. He realized what it was about, but did not put it into words, did not discuss it with anyone.

B.53-56: In those days, although writing words on tablets existed, putting tablets into envelopes did not yet exist. King Ur-Zababa dispatched Sargon, the creature of the gods, to Lugalzagesi in Uruk with a message written on clay, which was about murdering Sargon... (unknown number of lines missing).

C.1-7: With the wife of Lugalzagesi ... She (?) ... her femininity as a shelter. Lugalzagesi did not ... the envoy. "Come! He directed his steps to brick-built E-ana!" Lugalzagesi did not grasp it, he did not talk to the envoy. But as soon as he did talk to the envoy…the lord said, 'Alas!" and sat in the dust.

C.8-12: Lugalzagesi replied to the envoy: "Envoy, Sargon does not yield. After he has submitted, Sargon ... Lugalzagesi ... Sargon ... Lugalzagesi ... Why ... Sargon?"

Conclusion

Although Sargon and Ur-Zababa is routinely regarded today as a folktale, it may have been understood as history in its time – just as The Legend of Sargon of Akkad seems to have been – but, like the other works of its kind, would still have served as popular entertainment. Scribes in ancient Mesopotamia not only learned to read, write, and copy works but also to memorize and recite them. According to scholars including Samuel Noah Kramer, Jeremy Black, and Paul Kriwaczek, these compositions could have even been memorized by illiterate performers who would have then added them to their repertoire.

The poems concerning Sargon and his empire continued to be copied and recited century after century. Kriwaczek comments:

Most [of these fragments] read like dictation taken down as a record of an oral performance. From these fragments, many inscribed at least a millennium after the events they relate, we may guess that bards and other popular entertainers went on performing epic tales about Sargon and his dynasty for centuries after his lifetime. These tales tell of their protagonists' heroic prowess at arms, of their religious piety, of their overriding concern for personal worth and honor; of their boldly doing what no man had done before and boldly going where no man had gone before ...Yet, at the same time, the great kings can be shown in a very human light. (113)

The character of Sargon in Sargon and Ur-Zababa is just such a hero. He is presented as humble, faithful to his master, and trusting to the point that he suspects nothing even when he is given the message that is essentially his death warrant. The historical record supports the image of Sargon as a conqueror and empire-builder, establishing his rule and crushing any dissent, but in the legends and lore that grew up after his death, he is also the unassuming servant and friend of the gods whose devotion is rewarded not only by earthly power while he lived but also with immortality in verse, copied, sung, and recited long after his time on earth was through.