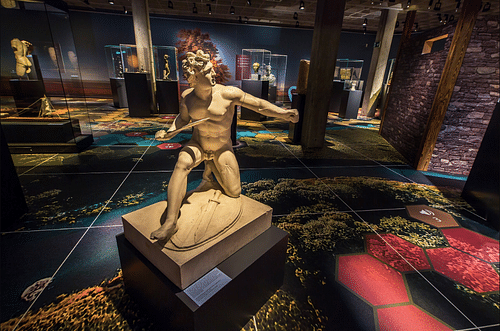

In ancient times, the Rhine was a major communications artery stretching right across Europe, allowing trade, contacts, and cultural exchange between different regions. Then as now, the river was of immense importance strategically for controlling trade routes and as a source of raw materials. Along the Rhine, Celtic, Germanic, and Mediterranean cultures met, fought, and influenced one another. A new exhibition at the Antikenmuseum in Basel, Switzerland – Ave Caesar! Romans, Gauls and Germanic tribes on the Banks of the Rhine – reevaluates the profound changes brought about by centuries of exchange in the region during Antiquity. James Blake Wiener speaks to Dr. Esaù Dozio, a curator at the Antikenmuseum, in order to learn more.

JBW: Many thanks for speaking with me yet again, Dr. Esaù Dozio. For thousands of

years, people have viewed the Rhine River as a boundary of sorts, dividing northern and

southern Europe. The Rhine River was a conduit of wealth and exchange. Nonetheless, I am curious to know why you and your fellow curators chose the Rhine River as the focus of the Antikenmuseum’s latest exhibition. I would suspect that Basel’s location, sitting astride the Rhine, had some role in this.

ED: Between fall 2022 and summer 2023, the Netzwerk Museen is dedicating an international exhibition series to the Rhine. Thirty-eight museums from Germany, France, and Switzerland highlight the importance of this river for our region from different perspectives. For the Antikenmuseum, it was a fitting occasion to present the ancient history of the Rhine. In this context, Basel and the surrounding region have a special role to play, especially since the Celtic settlement of Basel-Gasfabrik, the fortified oppidum on the local Münsterhügel and the nearby Roman colony of Augusta Raurica provide outstanding conditions for such a project.

JBW: Long before the arrival of the Romans, Greeks, and Etruscans had already made

their way to the Rhine River. Why were Greek and Etruscan merchants interested in trading with the Celtic inhabitants along the Rhine in Antiquity? What was their economic relationship like, and how is it reflected within the exhibition?

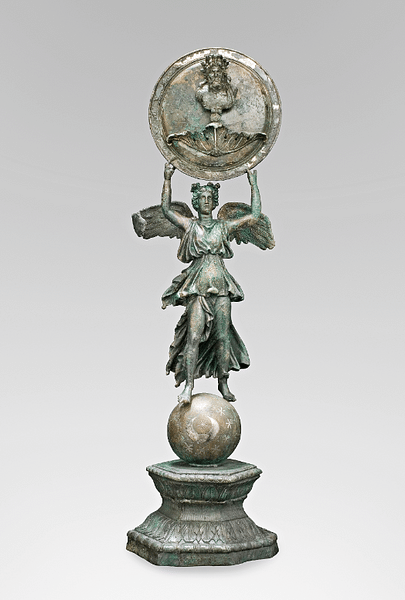

ED: These trade relations were very diverse. The Celtic upper class seems to have been particularly interested in wine as a prestige product, as well as in the ceramic and bronze

tableware associated with its consumption. For the southern traders, access to the tin deposits in Cornwall was very important, but also the Rhine gold, salt, furs, and, of course, slaves. In the exhibition, for example, Greek pottery from the Breisach Münsterberg and Etruscan bronze vessels from the vicinity of Bonn show the importance of such early "international" trade relations across Europe.

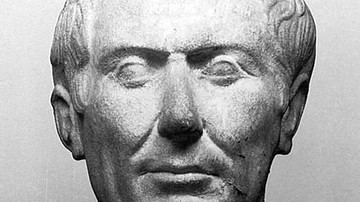

JBW: Between 58-52 BCE, Julius Caesar exploited quarrels between the Celtic tribes to expand Roman rule as far as the Rhine. The river thus became the frontier of the Roman

Republic. The Romans tried to acculturate locals – Germans or Celts – as much as

possible; local elites were allowed to keep their positions of power, too. With this in mind, how do we see the gradual acculturation of Celtic and Germanic peoples into the Roman world reflected in archaeological remains? Are there any objects in Ave Caesar, which show this process at work?

ED: Through Caesar's campaigns, no real upheaval can be observed on the Rhine.

Nevertheless, the direct presence of the Romans accelerated the already existing cultural

processes. This can be seen on all levels of society, from eating habits to architecture one now notices exciting news. The Romans very skillfully tried to integrate the native elites. Those who were willing to be loyal to the Roman power were granted Roman citizenship with its related privileges. This made him an active participant in the new political system. The Romans hoped this would provide a stable political situation in the newly conquered territories. Another factor of integration was the Roman army: Gauls and Germanic tribesmen from all social classes could join it, and in return, after the end of their service, they also received Roman citizenship for themselves and their own descendants: for many an important social advancement. In the exhibition, the helmet of the Gallic Sollionius Super as well as the grave stele of the Germanic horseman Niger testify to such a social development: being a Roman was not an ethnic coincidence, but primarily a political decision.

JBW: Tell us about the artifacts from the Roman country estates on show within the

exhibition – what do they reveal about the tremendous impact the Romans had on trade

and agriculture along the Rhine River? What do they tell us about the lifestyles of Roman

elites and plebeians in turn?

ED: With the Romans, the eating habits on the Rhine also changed. On the one hand, they improved the existing agriculture and animal husbandry. In the archeological layers from Roman times, for example, the bones of cattle are longer, from which we can conclude that the animals became bigger thanks to better breeding. During this period, new types of fruit were cultivated along the Rhine, such as grapevines, cherries, plums, coriander, etc. The Rhine region was now also a part of the globalized Roman world, so that pepper and cinnamon from India, for example, could be enjoyed here in our country.

JBW: Several Roman emperors spent time in close proximity to the Rhine. Who were these Emperors? I suspect it is fair to say that their time so close to the border left an indelible imprint on how they approached war and statesmanship.

ED: In the early imperial period, the Rhine frontier provided young Roman nobles with an excellent opportunity to demonstrate their leadership skills and make themselves popular with the army. Tiberius commanded a military campaign on the High Rhine under Augustus. Caligula, son of the famous general Germanicus, lived for two years in the legionary camps on the Rhine, later returning here as emperor. Vespasian lived in Avenches as a child and was legionary legate in Germania. Trajan and Hadrian also commanded legions on the Rhine. Many important figures in Roman history have seen the Rhine with their own eyes....

JBW: I have read previously that written culture also spread to the Rhine region thanks

to exchanges between Mediterranean peoples and Celts and Germans. What evidence is there for this across time and space?

ED: In fact, the Celts were not a written culture, so the first written evidence in our region is documented only from Roman times. Caesar nevertheless reports that the Gauls were quite capable of using Greek letters for short texts. The intensification of contacts with the south from the Latène period onwards also led to the adoption of certain cultural achievements, such as the minting of coins, north of the Alps. Writing, however, remained limited to certain individual cases. No wonder that the first known inhabitant of Basel by name was a Roman: it was only around the end of the first century BCE or the beginning of the first century CE that Titus Torius left his name on a luggage tag on the Basel Münsterhügel.

JBW: Esaù, Many thanks for introducing us to the exhibition and sharing your expertise

with us!

ED: Thank you very much and hope to see you again soon at the Antikenmuseum!

The exhibition runs until 30 April 2023 at the Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig in Basel, Switzerland.

Dr Esaù Dozio studied classical archaeology at the University of Basel in Switzerland and was also a member of the Swiss Institute in Rome, Italy. He has contributed to several exhibition projects, mostly in Switzerland and Germany, and since 2013 he has been a curator at the Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig in Basel, Switzerland.