Burial in ancient Mesopotamia was the practice of interring a corpse in a grave or tomb while observing certain rites, primarily to ensure the passage of the soul of the deceased to the underworld and prevent its return to haunt the living. Considerations of health in disposing of a corpse were secondary to spiritual concerns.

Ghosts in ancient Mesopotamia were understood as a fact of life, and this belief had a long history. Although there is no universal agreement among scholars on when burial first came to be associated with the prevention of hauntings, it seems to date from at least the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE) based on grave goods. It is possible, however, that the association and attendant funerary rites go back further. The earliest grave found thus far in the Near East is the Shanidar Cave in the Zagros Mountains, which dates to between 60,000 and 45,000 years ago and, according to some scholars, provides evidence of funerary rites. If so, this suggests an association between burial and an afterlife dating back to the time of the Neanderthals.

Funerary rituals were intended to honor the dead and send them respectfully on to the next world, but according to inscriptions from the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) onwards, there was a persistent fear the dead might return. Sometimes, a fugitive soul would manage to escape from the underworld by their own design, other times, they were given leave to return to the living to right a wrong or deliver a message, but the most common reason for a haunting was improper burial and funerary rites.

The deceased was supposed to be buried respectfully with grave goods and their final resting place tended by family members bringing food and drink offerings. Failure to observe the accepted burial traditions prevented the soul from finding their place in the afterlife, and as a restless spirit, they would return to haunt the living.

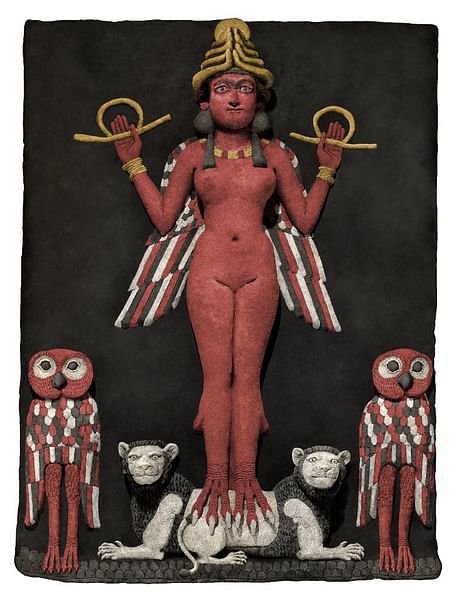

The afterlife in ancient Mesopotamia was a dim, gray world of inactivity in which souls were said to eat dust, drink from puddles, and stand or sit listlessly for eternity. Presided over by the goddess Ereshkigal (later with her consort Nergal), it resembled a prison far more than a paradise, and souls were thought to be ready to seize any opportunity to return to the light of the sun. Improper burial practices provided just such an opportunity, as Ereshkigal, who made sure the dead remained in her realm, could grant a soul a leave of absence to terrorize its relatives into tending to responsibilities they should have taken care of in the first place.

Gods, Life, & Spirit

According to the Babylonian flood story, Atrahasis (c. 17th century BCE), humans were created by the gods combining clay with the animating spirit and intelligence of one of their own: the god We-Ilu who sacrificed himself for this purpose. The goddess Nintu (Ninhursag) mixed the blood, flesh, and spirit with clay to produce the first 14 human beings, who were created to serve and assist the gods in their work. Humans were, therefore, a combination of an earthly body, which at death would decay and return to the clay it was made from, and the immortal spirit from We-Ilu.

The gods had created order out of chaos, but to maintain that order, they needed to work constantly. Humans were purposefully designed to take care of the day-to-day tasks of maintenance, so the gods were freed for their own responsibilities and pursuits. Humans, not gods, would now dig the canals and irrigation ditches, plant and harvest crops, build cities, populate the earth, and uphold the will of the gods and the established order.

When a person died, their intelligence – a gidim in Sumerian and etemmu in Akkadian – separated from the body. This spirit then required direction because its natural inclination would be to return to its point of origin, and as the gods were thought to live above the earth, this would have been upward toward their realm. The gods did not think it proper for human souls to inhabit their space, however, and so another was created for them below the earth – known as Irkalla – the realm from which none returned. Burial gave the soul direction toward Irkalla and, once arrived, ensured they remained there.

Funerary Rites

Cremation was discouraged by most of the Sumerian city-states because it was thought that if one's body was destroyed, one would have no form in the afterlife and would simply disappear, and, in various eras, also because the smoke from the cremation would travel upwards and carry the soul toward the gods instead of downward to Irkalla. Funerary rites and burial evolved to make sure the spirit of the deceased went where it was supposed to and, just as importantly, had no legitimate reason to return.

When a person died, they were said to have "lost their wind," and a common expression for a person's death was "His wind has blown away" (Finkel, 29). The spirit was then loosed, and its attention was brought back to its body through ministrations by the family. Scholar Stephen Bertman describes the deathbed scene of someone dying at home of old age, in childbirth, of injury, or an illness:

When the hour of death neared for an adult, the ancient Mesopotamian would lie in bed to await its coming in the company of loved ones, perhaps also with a priest in attendance. Beside the bed on the left sat an empty chair reserved for the spirit when it would rise invisibly from the corpse. Beside the chair lay the first spiritual offerings: beer and flat bread to strengthen the soul for its long journey to the underworld. When death finally came, the body would be washed, anointed in perfumed oils, and clothed, and laid out with jewelry and other favorite possessions. (281-282)

The corpse was sometimes given bread and water, as illustrated in the Sumerian literary text The Traveler and the Maiden, in which the maiden tends to the body of her deceased lover. Here, the food and drink are not set by the chair but are offered directly to the corpse and poured onto the ground to provide the soul with drink as it descended downward:

I dipped bread and wiped him with it;

From a covered bowl that had never been untied,

From a bucket whose rim was unannealed,

I poured out water; the ground drank it up.

I anointed his body with my sweet-smelling oil,

I wrapped up the chair with my new cloth;

Wind had entered him; the wind came out.

My wanderer from the mountains,

Henceforth, must he lie in the Mountain, the Netherworld.(Finkel, 30)

The "Mountain" was another term for the afterlife as the entrance to the vast underworld was thought to lie far away, beneath the mountains, and the soul required initial sustenance for that journey and then the further passage downwards, across a river, and into Ereshkigal's realm of twilight. The above rites were only the first step in preparing the deceased for that voyage, however, as once the body had been cleaned and anointed, it had to be properly interred.

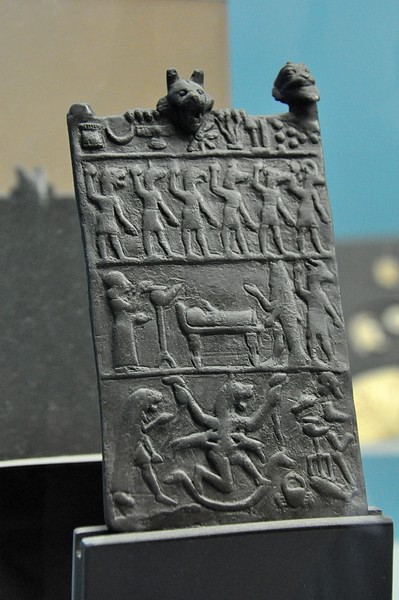

Burial

The earliest burials in Mesopotamia were beneath the floors of homes, and this practice continued throughout the region's long history. People buried their loved ones in residences as it would be easier to care for them through food and drink offerings than if they were interred in a cemetery outside of the city or village. Graves and tombs, in any era, were routinely dug into the earth to provide the soul with easier access to Irkalla, but one's final resting place could take several different forms. Scholar Irving Finkel gives the different types of burial in Mesopotamia:

- Burial within a wall: specifically infants and children.

- Earth or pit burial: the body wrapped in a reed mat in a pit dug under the floor.

- Shaft grave: shafts often led to pit graves, a sarcophagus, or a chamber.

- Jar or double jar burial: one corpse could be buried in a large and lidded, sealed jar, sometimes of domestic type, others specially made. Two jars joined at the mouth are found; it is a question whether such individuals will have died together if they are buried in such a way.

- Sherd grave: the interred body is covered with a blanket of broken pieces of pottery.

- Sarcophagus: a Mesopotamian sarcophagus would usually be made of ceramic, and covered over. A characteristic shape is that of the bathtub, with which specimens have occasionally been confused in the past.

- Specific structures: stone or brick cists beneath the ground or visible chambers of brick. (44)

In some cases, the chair that had been provided at the deathbed was preserved in the home so that, in the event the spirit returned as a ghost, it would find welcome and a place to rest and, hopefully, then return to its realm quietly. Figures of the deceased were also kept in the home as signs of remembrance, and grave goods were interred with the corpse to provide the spirit with their favorite possessions or necessary items. Finkel describes the items the family was expected to offer the spirit, even in modest forms:

- A clay effigy of the deceased. This was oiled and dressed and imbued with the identity of the departed and could or would be symbolically maintained within the family dwelling to provide a focus for remembering them and maintaining their presence within the family.

- The special chair for the ghost.

- Grave goods. These consist of what the deceased would need for the journey and when he arrived. The emphasis is on providing food and drink. Once in the netherworld, the sustenance available to the ghosts was, according to some authorities, inferior, and there is no doubt that the persistent emphasis on these offerings reflects sympathetic awareness of this situation. (30)

Not all burials followed the above forms, and not all rites were observed as described. As Finkel notes, "the commonest form of burial was to inter the corpse, wrapped in a reed mat, beneath the floor in a simple pit" but those who died of disease would be interred elsewhere (44-45). The concept of contagious disease was known to the Mesopotamians but, as they knew nothing of germ theory, interpreted it spiritually: the gods had allowed the person to die of the disease, for their own reasons but usually pertaining to some sin of commission or omission, and proximity to the corpse might taint the living by association.

Those who died in battle, on the sea, while traveling, alone on some errand, secretly murdered, alone in their homes, or in any other way that deprived them of the attention, assistance, and offerings of their families did not fare well in the afterlife. It was up to the living to not only see the deceased off on their final journey but to maintain them ever after.

Afterlife

Unlike the afterlife vision of civilizations such as Egypt, the Mesopotamian view of the underworld offered no reward for a virtuous life nor punishment for behaving badly. King and farmer, good and bad, all went to the same place and experienced the same dark, drab existence after death. One's immortal spirit was fully aware of one's state but could do nothing to improve upon it. What separated the suffering shade from the more contented spirit was the efforts of one's family on earth.

In Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Underworld, Enkidu relates his experiences in the afterlife as Gilgamesh questions him. In lines 254-267, Gilgamesh asks about the spirits of those who had sons to remember and care for them and asks, "Did you see him who had one son?" to which Enkidu replies, "I saw him. He weeps bitterly at the wooden peg which was driven into his wall" while, when Gilgamesh asks about the spirit who had seven sons, Enkidu says he rests content "as a companion of the gods, he sits on a throne and listens to judgments." The difference between the two spirits is that the first has only one son remembering him – a son who will eventually die and join him – while the second has many sons and so will continue to be honored longer.

Even those spirits elevated by the remembrance of their families, however, were still in the same dark realm as all the others; as were great kings. In The Death of Ur-Nammu, the Sumerian king Ur-Nammu (r. 2047-2030 BCE) arrives in the underworld, presents his offerings to the gods there, and, in keeping with his status, arranges a great banquet, but "the food of the nether world is bitter, the water of the nether world is brackish" (lines 83-84), and after a week there, he weeps for his life on earth. The same sort of experience is described in The Death of Gilgamesh where the hero-king of Uruk finds himself in despair after arriving in the underworld where, despite his honorable life, he is essentially little better than anyone else, even though, like Ur-Nammu, he had received a proper burial.

Ghosts & Spells

Gilgamesh and Ur-Nammu, as kings who had maintained order while they lived, accepted their fate, however grudgingly, but not every spirit was so inclined. Given the chance, the spirits of the dissatisfied dead were understood to seize any opportunity to return to visit the living and experience the sky and sunlight, rivers, and breezes. There is no record, however, of a ghost doing so quietly. It may be that ghosts would return invisibly and silently sit in the chair set out for them, but no one would have known if they had. Ghosts are recorded by the scribes in ancient Mesopotamia as troublesome spirits who needed to be sent back to where they belonged.

Among these was a "Let Me Enter" ghost, who begged the living for favors and needed to be returned to Irkalla by the recitation of a spell specifically for them. A doctor known as the asipu – who served in this capacity as an exorcist – would recite the appropriate spell for a certain type of haunting, sending the ghost back to Irkalla by naming it specifically or by type. These spells often began with a phrase along the lines of, "I banish you," followed by the type of spirit:

Be it a 'Let-me-enter, let me eat with you' [ghost]

Be it a 'Let-me-enter, let me drink with you' [ghost]

Be it an 'I am hungry, let me eat with you' [ghost]

Be it an 'I am thirsty, let me drink beer/pour water with you' [ghost]

Be it an 'I am freezing, let me get dressed with you' [ghost]. (Finkel, 36)

In the case of souls who had slipped out of Irkalla without permission, such spells would send them back. If a person had been improperly buried, however, or the family was not performing the acts of remembrance and offering expected, Ereshkigal would allow the spirit to haunt the family until they recognized their fault, made amends, and behaved as they were expected to.

Conclusion

In the same way one understood the reality of unseen wind by its effects, the ancient Mesopotamians recognized the invisible hand of ghosts in their daily lives. Even those spirits who could not be seen were understood to behave in certain ways and be the cause of various effects. Finkel defines three distinct beliefs of the ancient Mesopotamians which, taken together, support the claim that burial practice was primarily for the purpose of ensuring the dead would not return to the world or the living:

[These beliefs] are interwoven and interdependent to such an extent that one can hardly have prevailed without the others. All three are implied by burial: 1. Something survives of a human being after death. 2. That something escapes the grasp of the corpse and goes somewhere. 3. That something, if it goes somewhere, can quite reasonably be expected to be capable of coming back. (5)

It was up to the living to make sure the dead were as comfortable in their new home as possible, and the first step in this effort was proper funerary rites and burial. Afterwards, the quality of one's existence in eternity was determined not by what one had done in life but by how well one was remembered and honored after one's death.