Join World History Encyclopedia as they chat with Kaya Şahin about his new book Peerless among Princes, the Life and Times of Sultan Süleyman, published by Oxford University Press.

Kelly: Thank you so much for joining me today. It is a pleasure talking to you.

Kaya: Thank you, Kelly. I appreciate your invitation and the opportunity of talking about my book.

Kelly: I am very excited to talk to you all about your new book. So why do we not start with what it is all about?

Kaya: Okay. So the title is Peerless among Princes, the Life and Times of Sultan Süleyman. It is the biography of an Ottoman ruler who was sultan from 1520 to 1566. It is a biography, but at the same time, I wrote it as a life and times type of biography, so there is a lot of information about political and cultural developments in the Middle East and in the Eastern Mediterranean throughout the 16th century. In addition to the individual, I basically wanted to talk about a collective story of empire-building. It has many characters in it, both on the Ottoman side as well as among the rivals of the Ottomans. I tried to inject as many other individuals as I could into the narrative, as well as, as I said, providing a wider story of empire-building and regional and global history in the 16th century. I also thought it would be a good idea to add a full-colour insert in the middle in which I use different depictions of Suleiman. There are a couple of, I think, European depictions of him, but mostly Ottoman, and mostly from the 16th century. I also wanted to give my readers a sense of how his contemporaries saw and represented Suleiman. As I jokingly say, you have the book and you also have the comic book version in the middle. So it is a two-for-one!

Kelly: That is so cool! Did you find that the depictions of Suleiman the Magnificent changed either through time or by the types of people that were depicting him?

Kaya: Yes. So the depictions do change, and this is one of the reasons why I stayed close to 16th-century depictions. I would say the majority of the European representations of Suleiman were done by artists who did not see him. But at the same time, those are artists who had seen other more realistic depictions of Suleiman. They did a better job with clothing items and this and that. On the Ottoman side, again, when we look at the 16th-century artists, we see more of an emphasis on Suleiman and his surroundings and material culture, the different stages of his life. For instance, we can see him age in the 16th-century works. He goes from a younger man to a middle-aged person and to an older person. There is a sense of reality, of the passing of time, which disappears in later depictions, which become more idealized or which try to represent him in a single image that represents wisdom or martial values, or something like that. While the 16th-century depictions, especially the Ottoman ones, basically give you a more intimate and more detailed, more changing, more varied version of Suleiman.

Kelly: That is pretty incredible because I feel like, especially with rulers, you tend to get the same image with different clothes or whatever because they do want to portray a specific ideology. That is very cool that we can see the passage of time in the images. Did you want to just briefly tell us a little bit about Suleiman and the time period that he lived and ruled in?

Kaya: Sure. Suleiman was born in 1494 or 1495, we do not have the exact birth date. It could be either one of the two. He was born in a small town on the Black Sea coast, the southeastern part of the Black Sea coast, in the city of Trabzon. The city still exists today. And actually, if you were to visit Trabzon, you would be able to see the old Ottoman city; a good part of it has been preserved. It is on top of a hill going up from the seaside. At the time Suleiman was born, this was a small city, I call it a town in the book, with a population of around 6,000 to 8,000. He was there as the son of a prince. His father was a prince. His grandfather was the ruler of the Ottoman Empire when Suleiman was born.

Suleiman grew up in Trabzon, and then he received an appointment as a district governor himself when he was in his early teens, as was the custom of the Ottomans. Then during that time, his father waged a major succession struggle against the reigning sultan, who was Suleiman's grandfather and Suleiman's father's father. Suleiman's father basically prevailed. As a result of it, Suleiman became heir apparent. Then in 1520, as his father died, he came to the throne unopposed.

He basically spent the first part of his life under the stress of these kinds of things – life in a relatively small town in an isolated part of the Ottoman realm and the succession struggle that his father waged. I speculate a little bit about this in the book, but he must have thought oftentimes that he was bound to be executed by one of their rivals because, at first sight, his father was not the wealthiest or the most powerful claimant to the throne in the 1510s. After he came to the throne as the only candidate, he went through a period of transition during which he tried to prove himself. He tried to create a martial reputation for himself. He also tried to create a reputation for himself as a just ruler. We see him trying to get out from under the shadow of his father, who was a very famous and accomplished military commander. Then after the first couple of years of transition, we see Suleiman execute a fairly radical transformation of the upper echelons of the Ottoman elite.

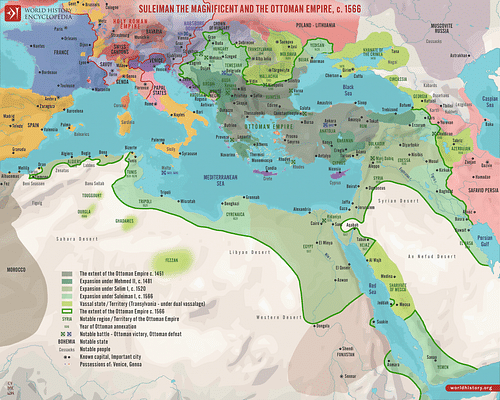

He starts kicking out the old guard and replacing them, and this is also the time in which he starts developing a fairly ambitious imperial agenda around 1524-1526. He basically takes on the already circulating rumours or bits of information about the arrival of the end time, apocalypticism, the pending emergence of a messianic leader who was supposedly going to lead humanity into a new age of salvation, and all of that stuff. There is a period from 1525 onwards during which he starts speculating with these kinds of ideas. Basically, he creates around himself a discourse of universal monarchy. He competes with the Habsburgs on the European front, both around the control of Eastern and Central Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean, but also around ideas like who is the true emperor. This may be quite surprising to those who are well-versed in European history, but Suleiman's period is a time in which the Ottomans also start using these kinds of ideas in their ideological speculations and in their political claims against the Habsburgs.

Suleiman engages in a very intense struggle with the Habsburgs from the second half of the 1520s to the end of his reign in 1566. The 1520s and 1530s, up to the mid-1540s, is the high point of his competition with the Habsburgs. He also has another rival further east, the Safavids of Iran. Now, this is a Muslim political entity, but the Safavids are Shia. They are not Sunnis, while the Arabs are Sunnis. So Suleiman also develops a new notion of the leadership of the Sunni Muslim community under the mantle of the Ottoman sultan. Just as he competes with the Habsburgs, both for strategic reasons as well as for ideological reasons, he also competes with the Safavids, again, pretty much to the end of his reign, around these kinds of ideological, political, and religious claims about who represents the more righteous version of Islam, who is the rightly guided and genuine leader of the Muslim community. Those kinds of speculations are very, very important in his political life. This is an agenda that he obviously inherits from others, but we can see that he was quite adamant about developing and furthering this agenda.

I am going on quite a lot about this to underline the fact that these pre-modern rulers – we usually have a patronising understanding of them as being less sophisticated than modern politicians or modern cultural figures – lived in a time in which there are these very complicated, very sophisticated cultural and political competitions. Another assumption that we often encounter in the modern period is that East and West, Muslims and Christians did not have a substantial dialogue. The life of Suleiman is proof to the contrary. You see it, especially in things like the accounts, daybooks, and reports of the Habsburg envoys who come to Constantinople in the 1520s and 1530s. You do see that the Ottomans and the Habsburgs, Christians and Muslims, Europeans and non-Europeans did have a lot of sophisticated and substantive discussions about these kinds of issues.

But to go back to Suleiman, I wrote the book chronologically from beginning to end for a couple of reasons. I wanted to talk about his childhood because almost nobody talks about his childhood. I also wanted to talk about his life by following the natural cycle of human life. After his difficult childhood, he comes to the throne, there are ideological speculations, and this and that. And then starting with the early 1540s, he hits middle age. The imperial project that he had managed and supervised in the previous decades also becomes ... – I do not want to call it less dynamic, but I would say less experimental. In middle age, he enters a period of institutionalisation, and he starts thinking about his legacy. He emerges as a major patron of charitable works. He supervises the composition of a major illustrated work of history that narrates the story of his reign, and this is a work that was completed in the late 1550s, but we know that the conception begins in the mid-1540s. He has a major mosque and a charitable complex around it, built to his name. It is called the Süleymaniye Mosque, and you can still visit it in Istanbul, and it is still an equally impressive building.

In the second half of his life, he starts building this legacy. The Ottoman Empire becomes more institutionalised in the sense that the bureaucratic apparatus expands. The legal institution, which is already considerable, expands further. There is renewed legislative activity, all of those kinds of things. So this is what happens around the middle period of his life. Then I would say he has a difficult late life. Again, a lot of the typical narratives of Suleiman do not necessarily talk about that. But first of all, he gets very sick. He has gout. As we know, members of aristocracies and upper classes throughout history basically get gout. He has a fairly severe case of gout that immobilises him at times for several weeks. For instance, in 1549, he is on campaign against the Safavids in the east. He has such severe gout attacks that he is completely immobilised for more than a month, and he starts shouting out of pain. His chief officials, so that the soldiers would not hear the sultan's scream, have martial bands playing outside his tent. His health deteriorates throughout old age. Now, I do not know whether gout leads to that, but it looks like he also has some other circulation-related problems and gastrointestinal problems, and these become worse and worse.

This is a political environment in which being a sultan is something very performative. Just as being a politician today is performative. But I would say in the 16th century even more so. In a martial and macho patriarchal environment, being an old person with severe health conditions is a very challenging thing. We see the emergence of rumours about him being replaced by one of his sons. He has a very challenging old age. He has one of his sons executed on the suspicion of rebellion. A couple of years after that, another one of his sons rebelled. This time, it is not an allegation anymore. One of his sons openly rebelled against him and against another son. He is not successful, he escapes to Iran, where he is imprisoned, and he is eventually executed in Iran.

In his old age, Suleiman lives something close to a Shakespearean tragedy. He is very keen on family life. I can see that. Sometimes when you write these kinds of biographies, you get the feeling that there are certain things that jump at you. I do not want to speculate, but in the case of Suleiman, unlike in the case of his father, there is a part of him that really wants family happiness, closeness, and a kind of intimacy. He is able to create that, but then in his old age, he also sees that family structure or family happiness implode under the strain of political tensions.

He gets sicker and sicker. He has two of his sons executed. He has another heir for the throne, but it is fairly obvious that in terms of dynamism, initiative, and skills, the remaining son is not the best candidate for the throne. He has another son who has a congenital defect. He also dies in 1555 of natural causes. But that is something that Suleiman finds very painful. It is very obvious. He spends the last decade and a half of his life dealing with these kinds of tensions. Then in 1566, he decides to go on one more campaign. Also, his beloved wife, Hürrem, dies in 1558. So he gets lonelier and lonelier. You start seeing it. I am not trying to humanise him that much because this is a person who decided over the fate of tens of thousands of people during his reign, but at the same time, you get to see these sorts of personal dimensions.

So, his wife dies in 1558, and then in 1566, he decides to go on one more campaign to prove himself, to remember the glory of his youth. It is not a very major campaign. He could have easily sent one of his frontier commanders or one of his ministers. But no, he insists on leading the army himself. And again, he keeps having health problems during the journey, he gets so sick that he is unable to ride on his horse. So they have a cart for him, which again is a loss of face because being on your horse and appearing to your soldiers are important things. And he dies in early September 1566 while besieging a Hungarian fortress that is of minor importance, I would say. So that is where he ends his life.

Kelly: Wow! Would you say that you wrote the book so that you could go into detail about the parts of his life that have not really been shown? Or is there another reason why you decided to write this biography?

Kaya: Why did I write it? Number one, I spent a good part of my life studying the 15th and 16th centuries, roughly the time during which Suleiman lived. I studied and I continue to study the 16th century as a major turning point in human history. The beginning of modernity, not necessarily or obviously the Western-Europe-dominated capitalist modernity, but a different modernity, or an early modernity in which non-Western actors and entities like the Ottomans, the Safavids, the Mughals in India, the Ming and then the Ching dynasties in China played crucial roles in the history of the world.

This is, as far as I see it, the first veritable age of globalisation in the sense that we are able to talk about globalisation in the circulation of goods, but also in the circulation of ideas and in these kinds of sophisticated and complicated exchanges among different polities. As such, I thought using Suleiman as a window through which I could get people to look into the complicated history of the 16th century might be a good idea. From an academic perspective, that is, I would say, the reason why I said yes to these two different invitations. I ended up writing this biography not to write a biography but to use a biographical perspective in order to tell a story about a wider period – something like that.

Kelly: Fabulous. That is incredible! While you were working on the book and doing your research, moving from one draft to the second, was there something in particular that struck you as incredibly fascinating or interesting or surprising that you were not expecting to read or learn about as you were researching?

Kaya: There are a number of things. First of all, in terms of the sources, I was once more amazed by the plurality of perspectives that you find in Ottoman, Safavid, and European historical and diplomatic sources of the period. These are really worth revisiting because this is a time in which both in Europe as well as in the Middle East and in other parts of the world, one of the consequences or reflections of this new globalisation but also a new age of empire-building is the explosion in the written word. People coming from different social backgrounds and people with different political agendas have written narratives about the time in which they lived. I knew that, but I realised, as a historian, you internalize the sources that you work on. While looking at them from the outside with a fresh eye, I was once again struck by how many different kinds of voices and approaches we can get from the sources of the period. As I was telling you a little while ago, I was also particularly fascinated by these European diplomats' reports, recollections of their service in Constantinople, and the dialogue about the political situation in Europe within the Ottoman Empire, or these sorts of ideological debates, how that dialogue was very, very, very lively and very detailed. That was also very fascinating.

Two more things are chance and contingency. Again, obviously, these are things that everybody is aware of. But still, even in a well-established empire, even within the well-regulated life of an imperial figure, chance and contingency play such important roles and they make everything so unpredictable. There are twists in the life story of Suleiman that had I read them in fiction I would have found them hard to believe. And yet here they are. His survival, his father's survival, for instance, during those succession struggle is nothing short of miraculous. Obviously, it is not a miracle. It is a matter of chance.

Kelly: That is incredible to hear. Thank you so much for joining me. It has been a pleasure talking to you about your new book!

Kaya: Thank you so much, Kelly.