Fashion and dress in Mesopotamia – clothing, footwear, and accessories – was not only functional but defined one's social status and developed from a simple loincloth in the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE) to brightly colored robes and dresses by the time of Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE). Styles changed, but essential form and function remained the same.

As in any civilization, the upper class and nobility wore more expensive clothes of higher quality, and by the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE), if not earlier, clothing identified one's social standing and, often, one's profession. In the prehistoric era, based on statuary, men and women wore the most basic articles of clothing, possibly made from plants, but as civilization developed, so did fashion and dress. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

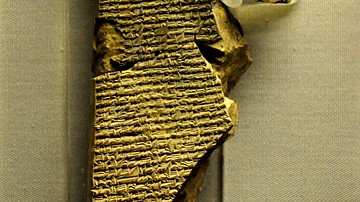

Archaeologists confirm that textiles were among the first of human inventions. Plant fibers may have been twisted, sewn, and plaited as far back as the Old Stone Age, some 25,000 years ago. (289)

In time, after the domestication of animals, wool became the most common basic material for clothing and leather for footwear (at least for the upper class). Wealthier citizens could afford brightly-dyed fashion, while poorer people wore basic white, though these clothes still seem to have been ornamented with designs, even as the skirts and loincloths of the Ubaid Period may have been.

Although Mesopotamia is often cited as creating clothing, among its many other 'firsts', people around the world would have developed the concept independently. Mesopotamia, however – specifically Sumer – is the first region in the world to have recorded the development of clothing and accessories through their art. Mesopotamian art and architecture provide evidence of this progress from simple to more complex styles, as well as how one's clothes "made the man" in establishing social rank.

Sumerian & Akkadian Fashion

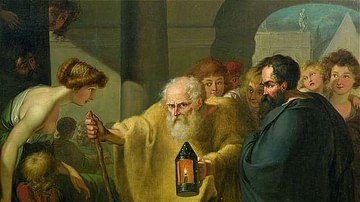

As with many modern-day aspects of life often taken for granted, clothing had a beginning, and this seems to have been the point at which people found the need to cover themselves, as Bertman observes:

According to the Bible, the founders of the fashion industry were Adam and Eve. For when they ate the educational apple and for the first time recognized their nakedness, they set about sewing fig leaves together to hide the bare truth. If Sumer was the geographical inspiration for the Garden of Eden, as many believe, the world's first clothes were labeled "made in Mesopotamia." (288-289)

Figurines from the Ubaid Period seem to depict women wearing simple loincloths and, in one case, an ankle-length skirt, without a top. By the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE), men and women wore ornamented, knee-length kilts or ankle-length skirts known as kaunakes and – based on evidence from cylinder seals and statuary – accessorized with hats, headbands, and jewelry. Some form of footwear is also evident in the artwork – most likely sandals – and, in some pieces, it seems the figures are also wearing decorated leggings under the kaunakes. Fashion at this time extended even to dog collars as evidenced by a golden dog pendant, dated to c. 3300 BCE, showing a striped collar whereas, earlier, dog collars appear to have been simple rope.

By the time of the Early Dynastic Period (though, as noted, possibly during the Uruk Period), the length of one's kaunake identified one's social standing. The lower class, including slaves, wore the knee-length kaunake, while royalty and the upper class wore the ankle-length style. Scholar Samuel Noah Kramer describes the fashion of this era:

The men either were clean shaven or wore long beards and long hair parted in the middle. The most common form of dress was a kind of flounced skirt, over which long cloaks of felt were sometimes worn. Later the chiton, or long skirt, took the place of the flounced skirt. Covering the skirt was a big, fringed shawl, which was carried over the left shoulder, leaving the right arm free. Women often wore dresses which looked like long, tufted shawls, covering them from head to foot and leaving only the right shoulder bare. Their hair was usually parted in the middle and braided into a heavy pigtail, which was then wound around the head. They often wore elaborate headdresses consisting of hair ribbons, beads, and pendants. (Sumerians, 100)

Based on artworks such as the Royal Standard of Ur (c. 2600 BCE), the king at this time wore a long robe (or the ankle-length kaunake without a shirt), while soldiers and attendants wore the short kaunake and a cloak fastened at the neck. Some artworks also show people wearing a simple tunic that appears to fasten at the shoulders and is belted at the waist. Musicians, dancers, and other entertainers also wore the short kaunake or performed in a loincloth.

Fashionable accessories during this era included necklaces and pendants worn by both men and women, rings, earrings, ornamental daggers, bracelets and armbands, and fringed shawls which may have been ornamented with beads. Men and women both used perfume, and the Sumerians seem to also have invented deodorant, possibly as early as c. 3500 BCE. Significant evidence regarding the fashion and accessories of the upper class during the Early Dynastic Period comes from the discoveries made at the Royal Cemetery of Ur by Sir Leonard Wooley in 1922, especially those associated with Queen Puabi (l. c. 2600 BCE), best known for her elaborate headdress.

The fashion of the Akkadian Period (2334-2218 BCE) followed the same basic form established by the Sumerians. Priests at this time, for example, wore the same ankle-length robes they had in the Early Dynastic Period, while both temple and palace personnel wore the short kilts. Temple and palace employees were both given a clothing allowance and, generally, were better dressed than the common people.

The Victory Stele of Naram-Sin (r. 2261-2224 BCE) shows the king in roughly the same sort kaunake as that worn by Sumerian rulers, and cylinder seals of others, such as scribes or merchants, depict clothing as similar to their earlier counterparts as well. Upper-class women's clothing seems to have become more highly ornamented during this period as evidenced by cylinder seals and statuary. The image of the poet-priestess Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE) has her in an ankle-length dress, possibly of descending layers, wearing a decorated hat. Headwear of the upper class at this time overall seems more highly developed than in earlier periods as seen in pieces such as the famous Bronze Head of an Akkadian Ruler, thought to represent Enheduanna's father Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE), founder of the Akkadian Empire. The bronze head wears an ornate cap over a metallic-looking headband and this same sort of headwear is also seen in cylinder seals of the time.

Footwear consisted of sandals or boots, and the practice of both men and women wearing jewelry continued. Carnelian was among the most popular gems of the time, as was lapis lazuli. Gems seem to have been used to ornament clothing as well as footwear and headdresses.

Babylonian & Assyrian Periods

The Babylonians maintained the same basic form in their dress but accessorized further. Their style of dress is famously described by Herodotus (l. c. 484-425/413 BCE):

As for their clothing, they wear a linen tunic which reaches down to their feet; on top of this they wear another tunic, made out of wool, and they put a white shawl around their shoulders. Their shoes are of a local design ...They wear their hair long and wrap a turban around their heads. They perfume their whole bodies. Every man has a signet-ring and a hand-carved staff, and every staff bears a design of some kind – an apple, a rose, a lily, an eagle, or something. It would be abnormal for any of them to have a staff which was not emblazoned with a device.

(I.195; Waterfield, 86)

Kings, of course, wore more complex outfits. The stele of the Code of Hammurabi, for example, depicts Hammurabi (r. 1792-1750 BCE) in a long robe, draped over his left arm, and a headdress. Fashion had extended to the gods by this time and, facing Hammurabi, is the god of the sun and of justice, Utu-Shamash, wearing a flounced robe of descending layers and a more intricate piece of headwear. In this image, both figures are bearded, but Babylonian men in general preferred to go clean-shaven.

Upper-class robes and tunics were made of linen and lower-class ones of wool. The basic form of dress for a man was some form of hat, a simple tunic (with additional layers if one could afford them), and sandals. Women wore the same basic outfit but with greater ornamentation and variation in accessories. As in the past, the length of one's clothing indicated social rank, as those with more money could afford longer tunics or robes. The lower classes of Babylonia, generally speaking, wore short tunics or kaunakes, no headdress, and carried no staff unless their job required it. Priests continued to be identified by their long robes and, because the goat was considered sacred, a goatskin shawl or wrap.

Men and women both wore cosmetics, especially kohl beneath the eyes to protect against sun glare, as well as jewelry. As with earlier Mesopotamian cultures, people carried cylinder seals as a form of identification and to seal legal documents, and this was sometimes pinned to one's robe or tunic. Men and women of the upper class favored brightly-dyed fringed clothing, which, because of the time it took to make, was out of reach of the lower classes.

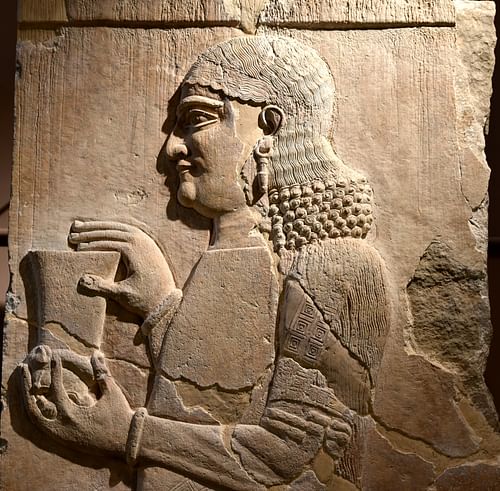

The Assyrians continued the kaunake-style of dress but with greater variation in color and a much higher degree of ornamentation. Assyrian clothing was more ornate and intricately accessorized than any of the Mesopotamian cultures that came before them. Clothing was primarily woolen, even for kings, although linen was used for some items worn as accessories by the upper class, such as scarves. Like the Babylonians, the Assyrians favored fringed garments and, according to written works – such as references in the Old Testament of the Bible – as well as pigment on statuary and reliefs, bright colors as well. The Book of Ezekiel 23:12, for example, describes the Assyrians as "clothed most gorgeously" (King James Version), and the phrase "Assyrian garments" came to be associated with high fashion.

One aspect of this was the bright colors that included deep purple, light green, vivid red, dark indigo blue, and vibrant yellow all produced from natural elements. Tunics and kaunakes were then decorated with imagery or repeated patterns like zigzags, dots, stripes, or lines along the hem.

During the Neo-Assyrian Period (912-612 BCE), specifically during and after the reign of Sargon II (722-705 BCE), Assyrian soldiers wore boots with leather breeches under a kaunake and a tunic beneath their armor while others wore boots or shoes and cloth leggings beneath the kilt, usually with some form of shirt or tunic belted at the waist. Women of the upper class wore long tunics and shoes or sandals and some form of headdress. Accessories during this period included the parasol, used by both men and women and famously featured in images of Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE), as well as earrings, armbands, bracelets, and necklaces.

Persian Fashion & Dress

The Persians brought Mesopotamian fashion to its height beginning with the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) and also, more than any of the preceding cultures, used clothing to express social status and occupation. As the Persian empires were multicultural, many different styles were worn (as evidenced by the reliefs at the city of Persepolis and elsewhere) but, essentially, each social class had its own 'uniform', whether royalty, clergy, military, or pastoralist (farmer/herder). Priests wore white robes, military commanders and soldiers dressed in red, and pastoralists in blue. The king wore robes of all three colors to symbolize sovereignty over all the other classes, at least in some eras.

Initially, according to Herodotus, the Persians adopted the fashion of the Medes, and the style was known as 'Median dress', which included footwear, loose trousers, a tunic, robe, jewelry, and a conical hat for the upper class and especially for what was known as 'court dress' – one's best clothing for appearing at court - while the lower classes generally lacked accessories or the means to layer or dye their outfits. Upper-class Persian fashion was defined by luxury, and the Median dress of the Achaemenid Period developed through the adoption of the styles and accessories of other cultures. Herodotus notes:

There is no nation which so readily adopts foreign customs as the Persians. Thus, they have taken the dress of the Medes, considering it superior to their own; and in war they wear the Egyptian breastplate. As soon as they hear of any luxury, they instantly make it their own. (I.135)

Persian men of every era between c. 550 BCE and 651 CE wore boots or shoes, pants, a shirt or tunic belted at the waist, a shawl or cloak, and some form of headwear. Persian fashion of the upper class relied on layers of clothing accenting each other to fully express wealth and power. The lower classes usually wore a knee-length kaunake with a shirt or shawl. Women wore tunics or dresses, sometimes belted, but always arranged to cover the body from the neck to the ankle. The clothing of both sexes was brightly colored but more so with women's wear, which was also more heavily ornamented or vividly decorated with patterns. Women sometimes wore veils, and noble women, as well as men, of the latter era of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE to 224 CE) and of the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE), especially, favored silk robes.

Conclusion

Fashion in Mesopotamia also included hairstyles, manicures, and pedicures, perfected by the Assyrians. Men and women both had their hair cut, oiled, sometimes dyed, and perfumed, or else shaved their heads and wore wigs. Perfume and deodorant were made from boiled aromatic plants ground and mixed with oil and could be very expensive, especially frankincense. Cosmetics, as noted, were worn by both men and women who regularly used body and face lotions, mascara, eyeliner, and lip balm.

Along with accessories such as jewelry, staffs, cylinder seals, and ornamented footwear and headwear, the production of Mesopotamian clothing became a thriving industry, as Bertman notes:

Due to the abundance of raw materials, the industriousness of workers, and the energy of merchants, textile manufacture became a major industry in Mesopotamia and a prime source of its wealth. Rather than being based in factories, however, the manufacture of ancient textiles was most likely a cottage industry, but one conducted on a large scale. Though physical evidence is scant, looms and a spindle are depicted in surviving works of art. (289)

From its beginning in Sumer, fashion in Mesopotamia developed throughout the Near East, retaining its essential form while becoming increasingly complex in ornamentation and style. By the end of the Sassanian Period, according to works from Persian art and architecture and written accounts, the basic form of the Sumerian kaunake, now accessorized, was in use from the regions of modern-day Turkey to the borders of India and remains the model for the kilt, skirt, and dress up through the present era.