The Hymn to Nungal (c. 2000-1600 BCE) is a Sumerian poem praising Nungal, the goddess of prisons and rehabilitation (also associated with the underworld), as well as the prison house she presided over. The piece, also known as Nungal A, was included as part of the curriculum of the scribal schools and was frequently copied.

The work is dated to the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE), owing to the number of copies found from that era, but may have been composed during the Ur III Period (2047-1750 BCE), possibly under Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE) whose interest in widespread literacy resulted in the establishment of more scribal schools (known as edubba, "The House of Tablets"), which encouraged a larger number of written works.

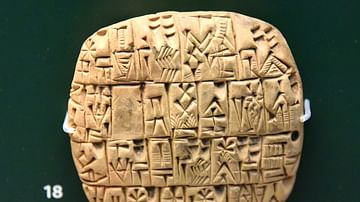

Nungal's name, however, (meaning "Great Princess", also given as Manungal) appears in the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE), and so the hymn, or some version of it, may have been composed during that time. The many cuneiform copies of the work were discovered in the ruins of the city of Nippur (and elsewhere in Iraq) in the mid-19th through the mid-20th centuries and its popularity established by the number of tablets found. The work formed part of the Decad of the scribal schools – ten compositions an advanced student needed to master before graduation – but is also thought to have been read aloud or recited at events honoring Nungal, a common practice during festivals in ancient Mesopotamia.

Commentary & Summary

Nungal was the daughter of Ereshkigal, Queen of the Underworld, and so was associated with the afterlife but also, as daughter-in-law of the sky god Enlil (who maintained order), with justice. Her consort, Birtum, was an underworld god, also linked with justice, whose name translates as "shackle". She is also referenced, symbolically, as a "daughter of An" (Anu), Enlil's father, also associated with justice/order. Laws such as the Code of Ur-Nammu and the Code of Hammurabi defined what constituted a crime and gave the corresponding punishment to be meted out by the authorities; but the gods were understood as the underlying power validating those laws. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

The key [to Mesopotamian justice] was an innate compliance to higher authority, a behavioral characteristic that permeated Mesopotamian culture. Society's prime personal virtue was humble and unquestioning obedience to the gods and their earthly surrogates. Within society, it was the state and its demands, rather than the individual and his rights, that were supreme. (70)

Several gods were associated with the concept of justice, most notably Utu-Shamash, but from the Early Dynastic Period through the Old Babylonian Period, and possibly later, the deity responsible for dealing with the accused after a crime was committed was Nungal, said to be able to separate the innocent from the guilty.

Imprisonment was only used as a temporary measure in Mesopotamian law – the accused would be held until guilt or innocence was established at trial or through the ordeal – and punishment then took the form of a fine, some form of mutilation, slavery or forced labor for a term, or death. The prison house described in the Hymn to Nungal – though thought to be modeled on actual Mesopotamian prisons – seems to exist in the underworld or a plane outside of the mortal realm in which Nungal punishes the wicked, rehabilitates the misguided, and rewards the innocent.

The Hymn to Nungal describes the prison house in lines 1-61 as the "jail of the gods" and as "a city in ruins" where inmates wander, unable to recognize even close relatives as they "pass the days in weeping and lamentation." This section, spoken by an unidentified narrator, gives the prisoners' view of Nungal's 'house' from which there is no escape. In lines 62-116, Nungal speaks, describing her house as "built on compassion" which "gives birth to a just person but exterminates a false one," exemplifying her role as a goddess of justice who is as interested in rehabilitation as she is in punishment. The poem ends with lines 117-121 in praise of Nungal and the "awesome radiance" of her prison house in dealing justly with the accused.

Text

The following is taken from The Literature of Ancient Sumer, translated by Jeremy Black et al., and from The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature, translated by the same. Ellipses indicate missing words or lines, and question marks suggest an alternate translation of a word.

1-11: House, furious storm of heaven and earth, battering its enemies; prison, jail of the gods, august neck-stock of heaven and earth! Its interior is evening light, dusk spreading wide; its awesomeness is frightening. Raging sea which mounts high, no one knows where its rising waves flow. House, a pitfall waiting for the evil one; it makes the wicked tremble! House, a net whose fine meshes are skillfully woven, which gathers up people as its booty! House, which keeps an eye on the just and on evildoers; no one wicked can escape from its grasp. House, river of the ordeal which leaves the just ones alive, and chooses the evil ones! House, with a great name, nether world, mountain where Utu rises; no one can learn its interior! Big house, prison, house of capital offences, which imposes punishment! House, which chooses the righteous and the wicked; An has made its name great!

12-26: House whose foundations are laden with great awesomeness! Its gate is the yellow evening light, exuding radiance. Its stairs are a great open-mouthed dragon, lying in wait for men. Its door jamb is a great dagger whose two edges ... the evil man. Its architrave is a scorpion which quickly dashes from the dust; it overpowers everything. Its projecting pilasters are lions; no one dares to rush into their grasp. Its vault is the rainbow, imbued with terrible awe. Its hinges are an eagle whose claws grasp everything. Its door is a great mountain which does not open for the wicked, but does open for the righteous man, who was not brought in through its power. Its bars are fierce lions locked in stalwart embrace. Its latch is a python, sticking out its tongue and hissing. Its bolt is a horned viper, slithering in a wild place. House, surveying heaven and earth, a net spread out! No evildoer can escape its grasp, as it drags the enemy around.

27-31: Nungal, its lady, the powerful goddess whose aura covers heaven and earth, resides on its great and lofty dais. Having taken a seat in the precinct of the house, she controls the Land from there. She listens to the king in the assembly and clamps down on his enemies; her vigilance never ends.

32-39: Great house! For the enemy it is a trap lying in wait, but giving good advice to the Land; fearsome waves, onrush of a flood that overflows the river banks (1 ms. has instead: which never stops raging, huge and overflowing (?)). When an individual is brought in, he cannot resist its aura. The gods of heaven and earth bow down before its place where judgments are made. Ninegala takes her seat high on its lapis-lazuli dais. She keeps an eye on the judgments and decisions, distinguishing true and false. Her battle-net of fine mesh is indeed cast over the land for her; the evildoer who does not follow her path will not escape her arm.

40-47: When a man of whom his god disapproves (?) arrives at the gate of the great house, which is a furious storm, a flood which covers everybody, he is delivered into the august hands of Nungal, the warden of the prison; this man is held by a painful grip like a wild bull with spread (?) forelegs. He is led to a house of sorrow, his face is covered with a cloth, and he goes around naked. He ... the road with his foot, he ... in a wide street. His acquaintances do not address him, they keep away from him.

48-54: Even a powerful man cannot open up its door; incantations are ineffective (?). It opens to a city in ruins, whose layout is destroyed. Its inmates, like small birds escaped from the claws of an owl, look to its opening as to the rising of the sun. Brother counts for brother the days of misfortune, but their calculations get utterly confused. A man does not recognize his fellow men; they have become strangers. A man does not return the password of his fellow men, their looks are so changed.

55-61: The interior of the temple gives rise to weeping, laments and cries. Its brick walls crush evil men and give rebirth to just men. Its angry heart causes one to pass the days in weeping and lamentation. When the time arrives, the prison is made up as for a public festival; the gods are present at the place of interrogation, at the river ordeal, to separate the just from the evildoers; a just man is given rebirth. Nungal clamps down on her enemy, so he will not escape her clutches.

62-74: Then the lady is exultant; the powerful goddess, holy Nungal, praises herself: "An has determined a fate for me, the lady; I am the daughter of An. Enlil too has provided me with an eminent fate, for I am his daughter-in-law. The gods have given the divine powers of heaven and earth into my hands. My own mother, Ereshkigal, has allotted to me her divine powers. I have set up my august dais in the nether world, the mountain where Utu rises. I am the goddess of the great house, the holy royal residence. I speak with grandeur to Inanna; I am her heart's joy. I assist Nintud at the place of child-delivery (?); I know how to cut the umbilical cord and know the favourable words when determining fates. I am the lady, the true stewardess of Enlil; he has heaped up possessions for me. The storehouse which never becomes empty is mine; ..."

75-82: "Mercy and compassion are mine. I frighten no one. I keep an eye upon the black-headed people: they are under my surveillance. I hold the tablet of life in my hand, and I register the just ones on it. The evildoers cannot escape my arm; I learn their deeds. All countries look to me as to their divine mother. I temper severe punishments; I am a compassionate mother. I cool down even the angriest heart, sprinkling it with cool water. I calm down the wounded heart; I snatch men from the jaws of destruction."

83-94: "My house is built on compassion; I am a life-giving (?) lady. Its shadow is like that of a cypress tree growing in a pure place. Birtum the very strong, my spouse, resides there with me. Taking a seat on its great and lofty dais, he gives mighty orders. The guardians of my house and the fair-looking protective goddesses .... My chief superintendent, Ig-alim, is the neck-stock of my hands. He has been promoted to take care of my house; ... My messenger does not forget anything: he is the pride of the palace. In the city named after (?) Enlil, I recognize true and false. Ninharana brings the news and puts it before me. My chief barber sets up the bed for me in the house imbued with awesomeness. Nezila arranges joyous (1 ms. adds: and valued (?)) occasions (?)."

95-105: "When someone has been brought into the palace of the king and this man is accused of a capital offence, my chief prosecutor, Nindimgul, stretches out his arm in accusation (?). He sentences that person to death, but he will not be killed; he snatches the man from the jaws of destruction and brings him into my house of life and keeps him under guard. No one wears clean clothes in my dusty (?) house. My house falls upon the person like a drunken man. He will be listening for snakes and scorpions in the darkness of the house. My house gives birth to a just person but exterminates a false one. Since there are pity and tears within its brick walls, and it is built with compassion, it soothes the heart of that person, and refreshes his spirits."

106-116: "When it has appeased the heart of his god for him; when it has polished him clean like silver of good quality, when it has made him shine forth through the dust; when it has cleansed him of dirt, like silver of best quality ..., he will be entrusted again into the propitious hands of his god. Then may the god of this man praise me appropriately forever! May this man praise me highly; may he proclaim my greatness! The uttering of my praise throughout the Land will be breathtaking! May he provide ... butter from the pure cattle-pen and bring the best of it for me! May he provide fattened sheep from the pure sheepfold and bring the best of them for me! Then I will never cease to be the friendly guardian of this man. In the palace, I will be his protector; I shall keep watch over him there."

117-121: Because the lady has revealed her greatness; because she has provided the prison, the jail, her beloved dwelling, with awesome radiance, praise to be Nungal, the powerful goddess, the neck-stock of the Anuna gods, whose ... no one knows, foremost one whose divine powers are untouchable!

Conclusion

As noted, the Hymn to Nungal was included as part of the curriculum of the scribal schools, was probably recited at festivals, and is thought to have encouraged compliance with the law through fear of the punishments that awaited transgressors. Jeremy Black comments:

This is one of the most menacing and unsettling compositions in the Sumerian literary corpus, posing difficult questions about the nature of justice and hinting darkly at the fate of criminals and transgressors in early Mesopotamia – for while the legal process is well recorded in law-codes and court records, the operation of prisons themselves is virtually undocumented. As a curricular composition, it sent a message to the scribes in training that it was their duty to uphold a just and fair legal system while showing what was in store if they did not. (Literature, 339)

At the same time, the poem provided hope of forgiveness for those who erred in ignorance or were led astray by circumstance in emphasizing the compassion and mercy of the goddess. Even if one had failed in observing the law, as Nungal says, there was still the promise that her house, in giving "birth to a just person," would offer an offender a second chance and redemption.