Mesopotamian education was invented by the Sumerians following the creation of writing c. 3500 BCE. The earliest schools were attached to temples but later established in separate buildings in which the scribes of ancient Mesopotamia learned their craft as they created and preserved the first written works in history.

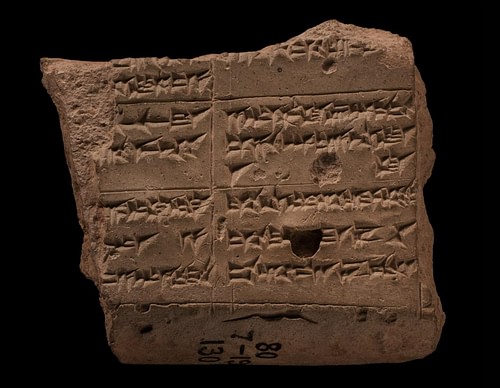

The scribal school was known as the edubba ("House of Tablets") as students wrote their works in cuneiform script on clay tablets. Scribal houses were first discovered in the mid-19th century when European and American archaeologists engaged in extensive excavations throughout the region of the Near East, especially in Iraq.

Based on information from tablets discovered in the ruins of the city of Nippur (primarily) and elsewhere, students entered school before the age of ten and graduated around twelve years later having mastered cuneiform script, Sumerian and Akkadian, and an array of subjects including agriculture, architectural design, astronomy, botany, engineering, history, literature, medicine, philosophy, religion, and zoology.

The basic form of the edubba was retained from its establishment prior to the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE) through the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (912-612 BCE). An educational system existed in the region after 612 BCE, modeled on the Sumerian edubba, but the clearest evidence for the schools and their operation comes from the Early Dynastic Period through the reign of the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE). The ruins of the Library of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh and those of the scribal school at Nippur have provided modern-day scholars with much of what is known of Sumerian literature and the Mesopotamian educational system.

Writing & First Schools

The Sumerians invented writing during the Uruk Period (4100-2900 BCE) c. 3500 BCE as a means of communication for long-distance trade. Trade in ancient Mesopotamia had, by this time, expanded from local exchange to long-distance commerce, and merchants needed to be able to communicate clearly with their representatives and clients in distant regions. Early methods, such as the clay balls known as bullae – containing tokens representing goods – gave way to pictographs, phonograms, and logograms (signs representing words) which became cuneiform script, modified c. 3200 BCE for ease of use but still requiring considerable training to master.

According to the Sumerian poem Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta, from the literary cycle known as the Matter of Aratta (dated to 2047-1750 BCE), writing was invented by Enmerkar of Uruk when his servant found his message to the Lord of Aratta too long to memorize. Enmerkar is said to have grabbed a piece of clay and reed stylus to write the message out. Although this is fiction, it describes what was no doubt a major incentive in working out written communication. Once a writing system was developed, it was necessary to preserve it and train others in its use, and this led to the establishment of the first schools. Scholar Stephen Bertman comments:

The oldest evidence, lists of vocabulary words, survives from the ruins of the city of Uruk and dates to around 3000 BCE, close to the time when writing itself was invented. From 2500 BCE come archaeological remains of the first real schools, at least two of which were established by royal edict. From between 2500 and 2000 BCE sufficient remains exist to document the operation of a true school system. Additional proof comes in the form of hundreds of cuneiform tablets, the actual homework and classroom exercises of ancient students, ranging from beginner to advanced, along with directions and corrections from their teachers and even literary vignettes of everyday life in a Mesopotamian school. The abundant evidence dates to between 2000 and 1500 BCE, and it comes from a whole array of cities. (301)

The earliest schools were part of the temple complex of a city and were staffed by priests, but by c. 2900-2500 BCE, schools were operating out of private homes or buildings constructed to serve the educational system. School buildings uncovered at Mari, Nippur, Ur, Uruk, and Sippar have classrooms featuring rows of baked clay benches for students and a space at the front for the instructor. Bertman notes:

A complete schoolroom likely would have had shelves on which completed work was laid out to dry, storage chests for miscellaneous school supplies and for the safekeeping of "textbooks" and perhaps an oven to bake selected clay tablets in order to give them permanence. (301)

Schools also had large ceramic vessels which held the damp clay that would be molded into writing tablets and others filled with water into which old tablets were dropped to soften so they could be erased, reformed, and reused. Students seem to have begun their education as early as the age of eight, attended class from sunrise to sunset for at least 24 days a month (possibly year-round), and graduated in their early twenties as scribes.

Student Body & Faculty

School was optional, not mandatory, and was funded by the parents of the students through tuition. Only the children of the upper class and nobility could afford to attend, and most of the student body was male. Daughters of nobles, merchants, or clergy were allowed to attend if they were going to follow in their parents' profession, but girls seem to have remained a minority throughout the history of the edubba. Slaves were also sometimes sent to school, especially those belonging to merchants or priests, so they could help with the scribal responsibilities of their masters.

Like Enmerkar in the poem, students began their education by taking a piece of clay and making marks in it with a reed stylus. By c. 3200 BCE, these 'marks' were not pictograms but 600 cuneiform characters, each of which had to be made precisely. Tablets, also, had standard shapes and sizes which were mandated by the instructors and formed by the students. Students, therefore, had to create their own writing tablets and then learn how to inscribe them with hand-made implements.

Writing in cuneiform on a clay tablet was not as easy as doing the same today with a pen or pencil on paper. As one wrote, one needed to turn the tablet in one hand while pressing the stylus into the clay with the other and each character had to be precise. Any student who failed in this was beaten by the teacher or the administrator in charge of discipline or both. The faculty was structured on the model of the family where the father was head of the household. The head of a Mesopotamian school, in fact, was known as the "Father of the Tablet House" and corresponded to today's school principal. Every other faculty member was an expert in his particular discipline, and older students, known as "big brothers", served as teacher's assistants in guiding younger learners.

Curriculum

After a student had mastered the basics of cuneiform script, they practiced writing signs and symbols, then words, then lists of vocabulary words which they would memorize. After these simple lists were mastered, they moved to more complex vocabulary words in various disciplines from astronomy to zoology. Students moved through four stages of instruction, and for each, they used a different type of writing tablet, given here according to scholar A. Leo Oppenheim as presented by Assyriologists Megan Lewis and Joshua Bowen of Digital Hammurabi:

- Type 1: large, multi-column tablets

- Type 2: 2-column instructor-student tablets

- Type 3: 1-column tablets with c. 25% of a composition

- Type 4: 'lentil-shaped' tablets with basic writing

Students began with Type 4 and progressed to Type 1 through the four stages:

- Stage 1: Type 4 Tablet – 'Lentil-shaped' tablets of simple writing exercises designed to teach a student to make proper wedges and signs.

- Stage 2: Type 2 Tablet – The instructor would write on the left side of the tablet and the student would copy that text on the right, often erasing errors – so the right side of the tablets found in the modern era are usually thinner than the left due to loss of clay. The reverse of the tablet held previous lessons of text already completed and memorized.

- Stage 3: Type 3 Tablet – These tablets hold a quarter or more of a long, completed composition that had been memorized.

- Stage 4: Type 1 Tablet – Complete compositions created from memory and demonstrating mastery of cuneiform script and subject matter.

The curriculum relied on proverbs, in all four stages, to teach students proper vocabulary, form, grammar, style, and interpretation. Ashurbanipal's collection of Sumerian and Babylonian proverbs, found in his library at Nineveh, include many that appear in the homework of students from the scribal schools. Proverbs were especially emphasized in the early years of one's education in preparation for the advanced stages of the Tetrad (four compositions) and Decad (ten compositions) that needed to be mastered, along with even more advanced works, before one could graduate.

Tetrad, Decad & House F Compositions

These works were discovered in numerous copies in the ruins of the scribal school at Nippur, designated by archaeologists as House F. Scholar Jeremy Black comments:

The House F literary tablets are strikingly representative of the Sumerian literary corpus as a whole. That is partly because they have deeply influenced our notions of what that representative corpus is; and partly because they originate from Nippur, where nineteenth-century American digs had already uncovered the vast bulk of known Sumerian literature…Nippur was also at the intellectual heart of Sumer, as the home of Enlil, father of the gods, and geographically close to its core. (xliii-xliv)

Although, as Black also notes, Mesopotamian literature was more diverse than the collection found at Nippur suggests, the same core curriculum works of the Tetrad and Decad found there have been unearthed elsewhere. These works, as given by scholar Eleanor Robson, are:

Tetrad:

- Lipit-Estar Hymn B

- Iddin-Dagan Hymn B

- Enlil-bani Hymn A

- Hymn to Nisaba (Nisaba A)

Decad:

- A Praise Poem of Shulgi (Shulgi A)

- A Praise Poem of Lipit-Estar (Lipit-Estar A)

- Song of the Hoe

- Hymn to Inanna B (Exaltation of Inanna)

- Enlil in the E-kur (Enlil A)

- Kesh Temple Hymn

- Enki's Journey to Nippur

- Inanna and Ebih

- Hymn to Nungal (Nungal A)

- Gilgamesh and Huwawa (Version A)

The works of the Tetrad were more difficult than the proverbs and other pieces students had mastered earlier, and those of the Decad were even more advanced. The other compositions found in House F (known as The House F Fourteen) were even more complex and the last works a student needed to master prior to graduation:

- Edubba B

- Edubba C (A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe)

- Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Netherworld

- Deeds and Exploits of Ninurta

- The Curse of Agade

- Shulgi Hymn B

- Ur Lament

- The Instructions of Shuruppag

- Edubba A (Schooldays)

- The Debate Between Sheep and Grain

- Dumuzid's Dream

- Farmer's Instructions

- Edubba Dialogue I

- The Debate Between Hoe and Plough

By the time one had mastered these compositions – which meant copying, memorizing, and reciting each one – the student was recognized as a scribe and focused on their area of interest (comparable to one's major in college) and then began their career. Bertman comments:

The goal of this educational system was to turn a child into a scribe. When grown up, the graduate of the Mesopotamian school system would be able to serve society by taking his place in the worlds of temple, palace, and business, drawing upon his skills in literacy and numeracy to excel at his job. Some might become professional scribes serving the practical needs of others; but others would follow their father's professions as government or temple officials or as businessmen. (303)

The student's life in pursuing this goal, however, was not an easy one. The satirical poem Schooldays describes this life which included rising early and getting to school on time, the work involved, and the daily beatings the student might expect for infractions of rules, including talking in class, leaving the grounds without permission, tardiness, rising from one's seat without permission, or failing to produce clean copy (not having a "good hand"), among others. A Supervisor's Advice to a Young Scribe is another satirical work on student life in which the young scribe is depicted as essentially the slave of his teacher until graduation.

Scribal Jobs & Works

Once graduated, however, the scribe was recognized as an elite member of society, known as a dub.sar ("tablet writer") in Sumerian and a tupshar (or tupsharru) in Akkadian. There was no lack of opportunity for a scribe as work was guaranteed at every level of society. Scribes were employed by the palace for administrative and diplomatic work as well as for the composition of songs, hymns, and inscriptions praising the king and recording his accomplishments. The temple employed scribes in administration and copying of sacred texts, and businesses employed scribes to keep their accounts and carry on correspondence with suppliers and customers.

Aside from these opportunities, scribes worked as architects, in construction, as engineers, astronomers and astrologers, brewers, doctors, dentists, surveyors, mathematicians, musicians, or any other career requiring literacy and a high degree of education. Scribes could also work for themselves as freelance writers in service to anyone who paid them for their work. A scribe could be hired by anyone who needed a letter or legal complaint written.

Scribes in ancient Mesopotamia created some of the most important works in world literature, including The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Descent of Inanna, and established genres still in use today as exemplified by The Instructions of Shuruppag (the oldest extant philosophical work), the Kesh Temple Hymn (the oldest extant work of literature, c. 2600 BCE), literary dialogues such as The Debate Between Bird and Fish, social commentaries like the Poor Man of Nippur and the Dialogue of Pessimism, dramatic monologues like The Home of the Fish, didactic works such as Inanna and Su-kale-tuda, and hymns like Shulgi and Ninlil's Barge or Hymn to Ninkasi which is both praise song and a recipe for brewing beer. These scribes are also credited with creating the world's first historical fiction through the genre known as Mesopotamian naru literature and setting down the first laws such as the Code of Ur-Nammu and the Code of Hammurabi.

Conclusion

The Akkadian priestess-poet Enheduanna (l. 2285-2250 BCE), the first author in the world known by name, learned her craft in the Mesopotamian scribal school, as did the Babylonian scribe Shin-Leqi-Unninni (wrote 1300-1000 BCE), who drew on earlier Sumerian poems to craft the standard version of The Epic of Gilgamesh. The names of most scribes, however, are unknown as their pieces would be defined today as work-made-for-hire, commissioned by their employer for a given purpose, not for self-expression, and attributed to the person who paid for it or published anonymously.

These nameless scribes, however, were ultimately responsible for the preservation of Mesopotamian languages, religion, and culture, and there were two famous monarchs – Shulgi of Ur (r. 2029-1982 BCE) of the Ur III Dynasty and Ashurbanipal of the Neo-Assyrian Empire – who understood this clearly. Shulgi of Ur not only encouraged the establishment of scribal schools throughout his kingdom but commissioned works for the express purpose of immortalizing his reign. Ashurbanipal sent delegations throughout Mesopotamia to bring back written works for the permanent collection of his library to preserve the culture "for distant days" – which, in fact, he succeeded in doing – and this was only possible due to the establishment and development of the Mesopotamian scribal school.