Trade unions were formed in Britain during the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840) to protect workers from unnecessary risks using dangerous machines, unhealthy working conditions, and excessive hours of work. The trade union movement was vigorously resisted by governments and employers, but by the 1850s, unions had grown powerful enough to win better protection and contracts for their members.

The Rise of the Machines

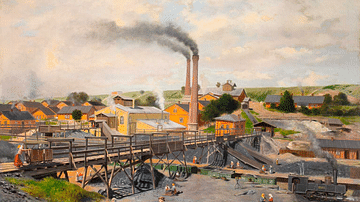

From the second half of the 18th century, the Industrial Revolution swept through Britain. Machines, especially steam-powered machines, helped make many factories fully mechanised and capable of mass-producing goods such as tools and textiles. New jobs were created, but these usually involved repetitive tasks and were ruled by the clock. Previously, workers had often been paid for a specific project (piecework) and worked at their own rhythm. Factories full of machines became hot, noisy, and often dangerous places to work. In textile mills, men, women, and children worked long 12-hour shifts.

In 1830, one in 80 Britons worked in a textile mill. The majority of these were women and children, both cheaper than male labour (women were around 50% cheaper, children 80% cheaper than adult males) and with other advantages such as having more dexterous fingers and less likely to cause upset to management. "A British survey undertaken in 1818 found that women comprised a little over half of the workers in cotton textiles with children representing another third" (Horn, 57). Children were used in many other industries, so much so that in 1851, "a commission found that one-third of children under the age of fifteen worked outside the home" (Horn, 57), and this survey did not count the considerable number of children who worked in agriculture.

Poor Working Conditions

The machines in factories had many moving parts, and these caused injuries to operators. Breakages were dangerous as pieces flew across the factory floor like bullets. Flying spindles were a particularly nasty possibility in textile mills. The atmosphere in a mill was deliberately kept damp to ensure the cotton threads stayed strong and supple. Many workers suffered health problems due to the constant humidity, particularly with their lungs. Loss of hearing from working in noisy factories was another common problem. It was not uncommon for raw materials dangerous to health (unknown or otherwise) to be used in various types of factories, for example, highly toxic substances like arsenic, lead, and mercury.

Even when the environment was relatively safe, there remained the common problem of repetitive stress injuries and physical deformity as workers carried out the same actions over and over again for hours on end. All in all, the poet William Blake was not overly exaggerating when in 1808 he described Britain's factories as "dark satanic mills" (Horn, 52). In 1831, one doctor, specifically sent to assess the physical well-being of a factory workforce in Manchester, noted:

Here I saw, or thought I saw, a degenerate race – human beings stunted, enfeebled, and depraved – men and women that were not to be aged – children that were never to be healthy adults. It was a mournful spectacle.

(Horn, 65)

Another doctor, this time in Leeds, collated the life expectancy of different societal groups. He found that the average life expectancy of manufacturers and the upper classes was 44, compared to just 19 for labourers.

As money and efficiency became the obsession of many mill owners, workers were increasingly pressured to work faster and not cause delays in production. There were fines for workers with dirty hands, being more than five minutes late, leaving a window open, or taking too long on a toilet break. Workers could be docked part of their wages if a manager felt they had not worked sufficiently hard during the week. There were cases, too, of the use of corporal punishment, even for adults. Most inventions in the Industrial Revolution were motivated by a desire to increase profits. Consequently, even when the machines were in use, the search for yet more profit was ongoing. As the historian J. Horn notes, "implementing labor saving was probably the most important function of managers and entrepreneurs" (56).

While employers varied in their treatment of workers, there was a general suspicion that employees never quite worked as hard as they might do as they had no long-term thoughts beyond weekly survival. One West Country entrepreneur rued: "The poor [labourer] in the manufacturing counties will never work any more time in general than is necessary just to live and support their weekly debauches" (Horn, 60). Working long shifts doing the same repetitive tasks was still a relatively new way of working that many struggled to cope with, at least according to one owner of a hosier factory who remarked that "I find the utmost distaste on the part of the men, to any regular hours or regular habits" (Horn, 60).

Part of the problem was that many factory owners, in particular, wanted their workers to be as efficient and tireless as the machines they operated. Long shifts from dusk to dawn and as few holidays as possible were the objectives of many employers for their workforce. Another regular and divisive problem was the strategy of employers cutting the wages of their workers whenever sales slackened off instead of settling for reduced profits. The workers knew full well the prevailing attitudes of their employers, as expressed in 1811 in this lament by cotton-spinning employees of Charles Lacy of Nottingham: "It appeareth to us that the said Charles Lacy was actuated by the most diabolical motives, namely to gain riches by the misery of his Fellow Creatures" (Horn, 64).

The Formation of Trade Unions

The poor conditions of many workplaces and the atmosphere of suspicion from employers that workers could always do more helped form the trade union movement in the late 18th century. Unions were often extensions of the craft guilds that had been in existence since the Middle Ages, which is why many of the early unions represented specialised workers like mechanics and printers. Trade unions sought to protect workers' rights from unscrupulous factory owners. Once unions were established, they were able to collect funds from members and help those workers who were sick or injured and so unable to work (and so were not paid). Unions also permitted the power of collective bargaining, where workers could improve their wages and contract conditions (if they actually had one). A union could also threaten an employer with a strike, where its members simply refused to work (but were temporarily paid by the union from its membership fees). Then there was the grey area between collaboration and resistance. Many workers registered their protest at what they regarded as unfair working practices by working more slowly, a difficult strategy for management to cope with.

Unions did not cater for working children, and these were left to face the challenges of corporal punishment, fines, threats, or instant dismissal that typified child labour during this period. Even for adults, the unions were often unable to protect their members. Some workers gave up altogether and emigrated, particularly to the United States, in the hope of finding a better working life there.

Restriction & Repression

Many business owners did not like the idea of workers getting together to limit their profits. "Managers attacked these organizations, breaking them whenever and however possible" (Horn, 62). If a union or worker's organisation could not be disbanded, then employers took aim at individuals. Workers who joined a union were often subject to prejudice and discrimination. The booming British population (from 6 million in 1750 to 21million in 1851) meant that there were plenty of people waiting to fill the position of a worker who had been fired for being excessively confrontational or militant. In the 1830s, many employers insisted a new hire sign a document declaring that they were not a member of a trade union.

Employers could take even more drastic action than instantly firing individuals. Faced with a demanding group of employees, owners threatened to (and often did) bring in an entire new workforce from a distant area of high unemployment such as the Highlands of Scotland or Ireland. Further, as industrialization became ever-deeper ingrained into the economy, a factory worker had very few skills that made them employable in any place except another factory. In the past, a hand textile worker might eventually save and set up their own business, but the gulf between employee and employer had become too wide for the vast majority of workers to now ever bridge.

Capitalists had the law and economics on their side, they also had society since the Victorian period witnessed a strong upper- and middle-class public support for 'improving' the poorer classes by having them work harder and live 'cleaner' lives. Capitalists also had most politicians on their side (many were politicians themselves). The government was lobbied by business owners, and so The Combination Acts banned trade unions or any sort of collective associations and activity by labourers between 1799 and 1824. Anyone caught breaching the rules faced up to three months in prison. In 1823, the Master and Servant Act effectively made striking impossible as it became a criminal offence not to complete one's work contract. Prosecutions numbered some 10,000 every year until the 1870s. The 1825 Combinations of Workmen Act specifically prohibited workers acting collectively to demand changes in their working hours or pay. The noose of the law was certainly pulled tight around the neck of the fledgling trade union movement, but some workers persisted, such as the 4,000 members of the Association of Colliers in the Rivers Tyne and Wear, founded in 1825.

Even when they were not officially banned, joining a union often carried a great risk. In 1833-4, for example, a small number of farm workers in Dorset got together to try and form a union, but the authorities arrested them on the dubious charge of having sworn an illegal oath on the Bible. All of the men were found guilty and transported to Australia. On the other hand, the government also tried to stop workers from emigrating; many types of skilled workers were legally forbidden from leaving Britain until 1824. The collective front of law, business, and government can be seen in the extraordinary decision in 1811 to make the breaking of machines (by such protestors as the Luddites who had lost their jobs to mechanization) an offence that could be punished by the death penalty.

Calls for a minimum wage or to somehow link wages to food prices were repeatedly ignored by successive governments, the usual excuses being not wishing to interfere in a private economic arrangement between worker and owner (laissez-faire economics), the perceived risk of restricting capitalist growth, and the need for 'everyone' to tighten their belts so that the nation could face such challenges as the Napoleonic Wars (1803-15). Not until 1871 and the Trade Union Act was participation in trade unions established as a legal right for workers, and even then unions could not 'intimidate', a loosely defined term that was often applied to anything from merely shouting to peaceful actions like picketing outside a factory.

Government Labour Reforms

Eventually, governments did what trade unions had struggled to achieve, and from the 1830s, the situation for workers in factories and mines, including for children, began to slowly improve. Several acts of Parliament were passed from 1833 to try, although not always successfully, to limit employers' exploitation of their workforce and lay down minimum standards. The first industry to receive restrictions on worker exploitation was the cotton industry, but soon the new laws applied to workers of any kind. New regulations included the minimum age children could work. The 1833 Factory Act stipulated that children could not be legally employed under 9 years of age, and could not be asked to work for more than 8 hours each day if aged 9 to 13, or no more than 12 hours each day if aged between 14 and 18. The same act prohibited children from working at night and made it obligatory for children to attend a minimum of two hours of education each day. There was, too, an obligation for owners to build protective screens for the more dangerous machines in their factories.

Although there were many abuses of the new regulations, there were government inspectors tasked with ensuring they were followed. These officials could demand, for example, age certificates for any child employee. The 1844 Factory Act limited men, women, and children's working day to 12 hours, dangerous machines had to be placed in a separate workspace, and sanitary regulations were imposed on employers. The 1847 Factory Act further limited the working day to a maximum of 10 hours. The Factory Commission still had far too few inspectors for the 4,000+ mills across Britain, but things were moving in the right direction, and more Factory Acts followed through the 19th century.

The trade union movement was also gaining in strength. By the 1850s, more skilled workers with better wages, such as engineers and carpenters, could afford to financially contribute enough to their union (around 5% of their wages) so that it had full-time employees dedicated to representing the union's interests. One criticism of these unions, even if several of the same trade joined together like the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (formed in 1851), was that they only furthered the situation of their own professions and not those of the wider workforce. A cross-union collaboration was attempted several times but was short-lived in each case. There were trade councils composed of a representative from various unions, but it was not until 1868 and the formation of the Trades Union Congress (TUC), a powerful federation of entirely different worker's unions, that real bargaining power for workers was achieved.

Trade unions did also make progress when they adopted a more employer-friendly approach of dialogue and negotiation, a strategy often called New Model Unionism. There was still, though, much work to be done to continue and increase the protection of workers from exploitation. It is notable that one of the harshest critics of the capitalist system, Karl Marx (1818-83), based many of his views on what he had witnessed firsthand in 19th-century British industry. The battle between labour and capital would go on raging right through the 20th century and, in many ways, continues in the present day.