La Rochelle emerged early in the French Reformation as a Protestant political and military center. The city's fortifications withstood repeated sieges over the years. In 1627, La Rochelle was besieged by Cardinal Richelieu (l. 1585-1642). The city's capitulation in 1628 ended the influence of the Huguenot political party and the religious ambitions of the city.

Early History

Although vestiges of human activity have been found in the area around La Rochelle as early as the 2nd century BCE, its first appearance in official documents was as a modest village in the 10th century CE during the Middle Ages. The city's name Rochella, or little rock, is drawn from its emplacement on rocky land. The industries of fishing and salt extraction led to the town's commercial growth and prosperity.

When Duke William X of Aquitaine (l. 1099-1137) destroyed the fortifications of nearby Châtelaillon in 1130, the fortunes of La Rochelle were assured. The duke supported the development of this new city by granting privileges designed to attract residents. At this time, the city had a single parish established by the monks of Cluny on the site where a church dedicated to Notre Dame was later erected. Demographic growth accelerated with the expansion of trade with other countries. The production of wine produced in Aunis and Saintonge, historical provinces of France, contributed to the city's prosperity. La Rochelle became the principal place of commerce between the Loire and Gironde regions and extended its domination on the small ports and islands that dotted the coastline. Toward the end of the 12th century, the arrival of the Knights Templar (l'Ordre du Temple) promoted commercial development and the expansion of the city's boundaries.

English Conquests

The city came under English control when Henry II of England (r. 1154-1189), the second husband of Eleanor of Aquitaine (l. 1122-1204), became king. Along with Bordeaux, La Rochelle developed into a commercial and military base for the king of England. It was from La Rochelle that King John of England (r. 1199-1216) launched his last military campaign before his definitive defeat by Philip II of France (r. 1180-1223) at Bouvines in 1214. The death of King John in 1216 led to turmoil among local lords who benefited from the weakening of royal authority. When King Louis VIII of France (r. 1223-1226) besieged the city in 1224, the inhabitants rallied in support of the French sovereign. The royal troops of Louis IX of France (r. 1226-1270) marched on Saintonge to reestablish order when the powerful Count Hugues de Lusignan (l. 1183-1249) rebelled against his sovereign and allied himself with the English. La Rochelle remained faithful to the king of France when English troops and their allies from Bayonne failed in their attempt to besiege the city in 1242.

A peace treaty with England in 1258 opened a long period of stability, and Louis IX confided the administration of the region to his brother Alphonse of Poitiers (l. 1220-1271). The official rupture of relations between England and France in 1337 led to the Hundred Years' War (1337-1453). During this period, the majestic Chain Tower and Saint Nicolas Tower were erected at the entrance of the port. Despite the instability of this dark military and political period, the city maintained its allegiance to the French Crown. The defeat of the French and the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360 brought the city under English control. In September 1372, the city's mayor, Jean Chaudrier, opened the gates to French troops, and French control was restored. In the early 15th century, the conflicts continued on the sea as English naval forces extorted ships from La Rochelle and other nations. While the kingdom sank into civil war, the Rochelais announced their intention to remain neutral in 1419, although they welcomed with enthusiasm Charles VII of France (r. 1422-1461) in October 1422.

16th-Century Reformation in France

In the 1540s, the teaching of John Calvin (l. 1509-1564) spread rapidly throughout the kingdom. As an active, cosmopolitan city with international contacts and an absentee bishop established at Saintes, La Rochelle was won over by the Protestant cause in the early years of the Reformation. The city became part of the Huguenot crescent of Protestant congregations that stretched from La Rochelle to the Dauphiné valleys. In 1558, the 'father of the Church of La Rochelle,' Pierre Richer (c. 1506-1580), organized the first Reformed church and consistory, and by 1560 Protestants comprised over half the population of La Rochelle.

Reformed believers gathered discreetly for worship until 1561, at which time Catholics and Protestants met at different times in the churches Saint-Sauveur and Saint-Barthelemy. After the massacre of Huguenots in Vassy in 1562 began the French Wars of Religion, Catholic churches were destroyed, and monks and nuns were driven out. The city was retaken by royal troops and then returned to Protestant control with the Edict of Amboise in 1563, which ended the First War of Religion.

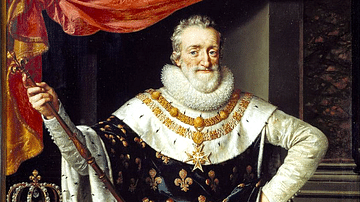

In 1565, the city welcomed the young Charles IX of France (r. 1560-1574), who, with the queen regent, Catherine de' Medici, sought to revive the monarchial fervor of their subjects. The king, however, refused to confirm the city's privileges and threatened pastors who troubled the public order. Ten-year-old Henry of Navarre, the future Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610), was in the royal entourage. La Rochelle became a citadel of the Protestant party and seized the Island of Ré. The Treaty of Longjumeau in 1568 ended the Second War of Religion before royal troops arrived to besiege the city. During the Third War of Religion (1568-1570), the city's magistrates sided with the Protestant majority. La Rochelle, under the leadership of the Queen of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret (l. 1528-1572), operated as a quasi-sovereign state within the kingdom of France and made political alliances with Protestant powers.

After the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre on 24 August 1572, when Huguenots were attacked by Catholics, many Protestants found refuge in La Rochelle, one of the cities along with Montpellier and Nîmes where Protestantism dominated the religious landscape. In 1573, the city was besieged by royal troops under the command of the Duke of Anjou, the future Henry III of France (r. 1574-1589). After failing to take the city, the Edict of Boulogne was signed in July 1573, which ended the Fourth War of Religion. The edict granted Protestants freedom of worship in the cities of La Rochelle, Montauban, and Nîmes.

In 1598, the Henry IV of France and the Edict of Nantes opened access for Protestants to universities and public offices, and four academies were granted authorization along with the right to convoke religious synods. Protestants were guaranteed the security of their garrisons for eight years in several towns, most notably the port city of La Rochelle. La Rochelle became the principal bastion of the Reformed religion and was supported by England, which sought to curb the development and expansion of the French navy.

17th-Century Conflict

When Henry IV was assassinated in 1610, the Edict of Nantes was progressively undermined by his son, Louis XIII of France (r. 1610-1643). Despite a decade of relative peace, Reformed believers knew they were only tolerated in the kingdom of France. Their security depended on the goodwill of the king and the fortifications of the city of La Rochelle and other strongholds. Protestants were also alarmed by the pro-Spanish policy of Henry IV's widow, Marie de Medici (l. 1575-1642). There were also divisions among Protestant leaders: those who were submissive to royal authority and those prepared to fight for their political and religious rights. The greatest resistance came from cities where Calvinism and independence were combined.

The city of La Rochelle, the principal stronghold of the Huguenot party, stood as a formidable barrier to the designs of Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu. La Rochelle had largely adhered to the Protestant Reformation, was responsible for the dissemination of Protestantism in western regions of France, and had become a refuge for Protestants fleeing other places. La Rochelle was the most secure and well-armed city of the French Reformation. At the general assembly of Catholic clergy in 1617, Louis XIII ordered the restitution of confiscated possessions to the Catholic Church. He marched on the province of Béarn and reestablished Catholicism. In response to the king's actions, the Huguenot general assembly at La Rochelle in December 1620 divided France into eight quasi-military regions with leaders. This strategy triggered Catholic opposition and led to military intervention. Fortified towns in Saintonge, Guyenne, Languedoc, and Dauphiné took up arms against royal troops.

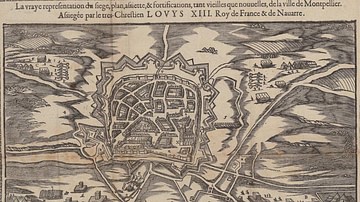

When the Peace of Montpellier was signed in October 1622, Protestants lost 80 places of refuge. Nîmes, Castres, Uzès, and Millau were ordered to demolish half of their fortifications, and Montpellier became an open city. Only two stronghold cities remained: La Rochelle and Montauban. Around La Rochelle, the king reinforced the fortification of Fort Louis, and the Duke of Guise based his fleet on the island of Ré. La Rochelle was ordered to dismantle a part of its fortifications even as the king built new ones around the city and reinforced the garrisons. Through these measures, the king sought to ensure the city's compliance. He also feared the English, with whom relations had deteriorated since the marriage of Henrietta Maria (l. 1609-1669), daughter of Henry IV and Marie de Medici, with Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649). The Peace of Paris was signed on 5 February 1626 and maintained the status quo until Cardinal Richelieu arrived on the scene.

Cardinal Richelieu

Cardinal Richelieu had made the ruin of La Rochelle and the Huguenot party a personal affair. No city in the kingdom was more independent and better fortified. Sometimes English, sometimes French, Catholic, then Calvinist, and attacked by one or the other according to events and the whims of princes, its military power and walls had maintained the city's autonomy for decades. With its privileges from another time, La Rochelle represented to Richelieu an anachronism as well as a danger for the Crown.

Richelieu did not hide his intention to establish the king's absolute authority on the ruins of the city. Louis XIII announced this intention to the pope, who had been troubled by reports of a treaty with the Huguenots. The archbishop of Lyon wrote to Richelieu to encourage the siege of La Rochelle, to punish, or even better, to exterminate the Huguenots. In the spring of 1627, the conflict was reignited. England and France were on the verge of a rupture in relations, and Louis XIII forbade his subjects to trade with England. This was a blow to the independence of the inhabitants of Rochelle, who in 1472 had been granted the privilege by Louis XI of France (r. 1461-1483) to trade with all countries, even with the enemies of the king. Under the leadership of George Villers (l. 1592-1628), the Duke of Buckingham, the English sailed towards the island of Ré in the summer of 1627 but left after fierce resistance.

The Siege of La Rochelle

Richelieu resolved to block all access to the city and force its surrender. Fortifications were constructed outside the city to prevent land access to the city. The entire city was mobilized and confident of its power to resist a siege. The walls were bristling with artillery units, and the city was well-armed. Richelieu soon understood that the only way to bring down the city was to close off access to the port. He ordered the construction of an enormous dike to prevent ships from entering the port. Although they faced 25,000 men, the Rochelais were confident that the dike would not resist the winter storms. In the spring of 1628, the dike still stood. On 11 May, the English showed up, approached La Rochelle, fired a few cannon shots, and soon retreated without supplying the inhabitants.

La Rochelle was besieged for a year, encircled, and cut off from all outside provision. The last months of the siege were marked by a devastating famine, obliging women, children, and the elderly to leave the city and wander destitute through the marshes, where few survived. Those besieged survived by eating horses, dogs, and cats, with hundreds dying daily of famine. Those who left the city to forage for food were cut down by ruthless soldiers. La Rochelle had a population of 25,000 before the siege, of which 18,000 were Protestant, and little more than 5,000 inhabitants remained when the blockade ended.

La Rochelle capitulated on 28 October 1628. The next day Richelieu entered the city and celebrated a solemn Mass in the Church of Sainte-Marguerite. Louis XIII entered La Rochelle on 1 November to receive its surrender, followed by a grand procession on 3 November. The king abolished all the former benefits the city enjoyed, ordered most of the ramparts leveled, turned Protestant temples over to the Catholic Church, and created a bishopric. La Rochelle's destiny was now tied to the French monarchy and the Catholic Church. There was a great celebration at the news of La Rochelle's capitulation in Rome. A Te Deum was raised to heaven, and Pope Urban VIII (p. 1623-1644) made an extraordinary distribution of indulgences. He assured the king that God was at his right hand.

Conclusion

The fall of La Rochelle put an end to its inhabitants' dreams of independence. Religious tolerance was guaranteed with the Peace of Alès in 1629, but the Huguenots no longer had political rights. The ramparts of the city were razed, and Catholicism was restored. Apart from present Protestant residents, no other Protestants were allowed to move into the city. The fall of La Rochelle marked the rise of monarchical absolutism in France. The privileges of La Rochelle had been symbolized by an ancient custom. When a monarch wanted to enter the city, a silk cord was hung across the door opening. The mayor, before cutting the cord, made the illustrious visitor swear on the Gospel to respect local liberties and privileges. Louis XI himself had bowed to this custom. But when Louis XIII entered La Rochelle on 1 November 1628, he entered as a conqueror, and the Rochelais bowed before him.