The Hymn to Ninkasi is at once a song of praise to Ninkasi, the Sumerian goddess of beer, and an ancient recipe for brewing. Written down in c. 1800 BCE, the hymn is no doubt much older as evidenced by the techniques it details which scholars have determined were actually in use long before the hymn was written.

Scholar Paul Kriwaczek states that the hymn reflects "the techniques of a thousand years earlier" and notes how, by the time the work was written, there were many different varieties of beer in Mesopotamia and new methods employed in brewing (83). The Babylonians had at least 70 varieties of beer and there were no doubt many more which were either left unrecorded or evidence of them has not yet come to light.

Most likely, the Hymn to Ninkasi was preserved in oral form because it had become a popular song and was finally committed to writing. The light-hearted tone of the verse and its praise of a drink, and a goddess, many admired no doubt also contributed to its preservation. The recipe has been proven sound in the modern age in 1989, producing a beer reminiscent of champagne with bouquet of dates, known to be an ancient sweetener in Mesopotamia.

The Beginning of Beer in Mesopotamia

Evidence for brewing beer in the Mesopotamian region dates back to 3500-3100 BCE at the Sumerian settlement of Godin Tepe in modern-day Iran where, in 1992, archaeologists discovered chemical traces of beer in a fragmented jar dating to the mid-4th century BCE. The same site also yielded evidence for early wine-making and it is thought that the idea of brewing beer arose from baking. The fermentation process evident in grains, which may have been left out unattended, could have inspired the creation of both wine and beer.

Although this theory has long been accepted, scholar Stephen Bertman notes that grains may have actually been cultivated specifically for brewing beer. He writes:

Though bread was basic to the Mesopotamian diet, botanist Jonathan D. Sauer has suggested the making of it may not have been the original incentive for raising barley. Instead, he has argued, the real incentive was beer, first discovered when kernels of barley were found sprouting and fermenting in storage. (292)

However it was first discovered, as Bertman notes, "beer soon became the ancient Mesopotamian's favorite drink" (292). Although the craft of brewing would eventually be practiced across the region, it began in the small village of Godin Tepe and, almost certainly, was initiated and cultivated by women.

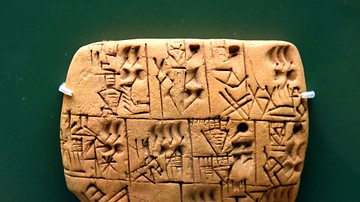

Godin Tepe was a Sumerian outpost, first inhabited c. 5000 BCE, which became a significant town and fortress along the famous Silk Road trade route. That evidence for the brewing of beer should be discovered there is not surprising as beer was the drink of choice among the ancient Sumerians; one of the most common pictographs found in Sumerian cuneiform is the one for beer.

The Ebla Tablets (discovered in Syria in 1974) dating from 2500 BCE, provide evidence that Ebla, another Sumerian outpost, was brewing significant quantities of beer at that time using many different recipes. As only fresh water was used in beer, and had to be boiled, it was healthier to drink than water from the canals which could be polluted by animal waste. Scholar Jeremy Black writes:

Beer was a staple in Mesopotamia and its surroundings from prehistoric times, as the fermentation process was an effective method of killing bacteria and waterborne disease. Its manufacture was recorded and controlled by scribes even in the earliest written records, from the late fourth millenium BCE. Beer was consumed by people at all levels of society and offered to gods and to the dead in libation rituals. (297)

Beer also contained nutrients other beverages did not and, as Black notes, was a staple in the daily diet of the people throughout Mesopotamia. Laborers were provided with beer as part of their daily rations (a practice also observed in Egypt) and, based on art works as well as writings, it was a drink enjoyed by the lowest laborer to the highest noble and was consumed through a straw. Kriwaczek notes:

There seem to have been many varieties of Mesopotamian beer, brewed to different strengths and, in the absence of hops, flavoured with different ingredients. It has generally received a rather bad press in the academic literature. The fact that it was often drunk through straws from large containers suggests to many academics - who may, as a class, have special expertise in beer - that it was full of particles and grit that were excluded by the straw...This is surely unfair. The Sumerian beer was carefully filtered. (83)

The straw, developed by the Babylonians, was first invented by the Sumerians specifically for the purpose of drinking beer and, no matter how carefully filtered that beer was, it does seem that the straw was used to keep a drinker from the unpleasant experience of consuming sediment in the beer. From the evidence of art works found throughout Mesopotamia, it is clear that beer was consumed daily in great quantities by the people, sediment or no, and developed from a cottage industry into a lucrative commercial enterprise. The commercialization of beer is evidenced by The Alulu Tablet from the city of Ur, an ancient receipt for the delivery of beer by the brewer Alulu, dated to 2050 BCE.

The Drink of the Gods

Beer was also the drink of the gods. This is evident from a number of myths such as the poem Inanna and the God of Wisdom where the goddess Inanna and the god of wisdom Enki get drunk together and Inanna is able to trick him into giving her powerful elements she needs for her city.

In this poem, Enki loses face through drunkenness and, in the poem Enki and Ninmah, the goddess Ninhursag loses prestige when she is beaten in a drinking game by Enki. The inability to "hold one's drink" is regularly depicted as a weakness but beer itself is never criticized; it is the fault of the drinker if he or she is unable to maintain self-control while drinking. Beer was created to make the heart feel light and the goddess responsible for such elevation was Ninkasi.

As in the case of goddesses like Nisaba (patroness of grains, accounts, writing, and scholarship) Ninkasi was both the brewer of beer and the beer itself. Nisaba was not just the goddess of grain but the actual grain and, once she became goddess of writing, she was not just an impartial overseer of the craft but the craft itself; the same is true of Ninkasi. Her spirit and essence infused the beer produced under her guidance.

Ninkasi, and therefore beer, was associated with healing because she was born through the ministrations of the Mother Goddess Ninhursag when she was healing Enki, who was sick and close to death. As Ninhursag draws out Enki's afflictions, a new deity is born and, among these, is Ninkasi. Each of the supernatural beings born this way goes on to produce some great benefit for humanity, such as Nanshe - goddess of social justice and divination - and, in keeping with Mesopotamian tradition in which the clergy who served the deity were of the same sex, the clergy of goddesses like Nisaba, Nanshe, and Ninkasi were women.

The priestesses of Ninkasi were the first brewers and this is hardly surprising since women, generally, had brewed beer in the home until commercial production of the beverage began and men started taking over. Most ancient depictions of brewers clearly show them as women in both Mesopotamia and Egypt although, once brewing became a commercial enterprise, males are shown supervising the female brewers.

Whoever supervised or brewed the beer would not have mattered to the goddess herself; her responsibility was to the end result of the finest drink possible. Ninkasi was said to make the beer fresh every day from the best ingredients and her priestesses would have followed suit as the hymn is, again, not only a praise song but also instructions on how to brew beer.

The Hymn to Ninkasi

In an age where few people were literate, the Hymn to Ninkasi, with its steady cadence, provided an easy way to remember the recipe for brewing beer. One began with flowing water, then made Bappir (twice-baked barley bread) and mixed it with honey and dates. Once the bread had cooled on reed mats it was mixed with water and wine before being put into the fermenter.

After the brew had finished the fermentation process it was placed in the filtering vat "which makes a pleasant sound" and then placed "appropriately on a collector vat" from which the filtered beer was then poured into jars. According to the hymn, the pouring of the beer was "like the onrush of the Tigris and Euphrates" which is taken to mean that, like those two rivers, beer brought life to those who drank it.

The following translation of the Hymn to Ninkasi is by Miguel Civil:

Hymn to Ninkasi

Borne of the flowing water,

Tenderly cared for by the Ninhursag,

Borne of the flowing water,

Tenderly cared for by the Ninhursag,Having founded your town by the sacred lake,

She finished its great walls for you,

Ninkasi, having founded your town by the sacred lake,

She finished its walls for you,Your father is Enki, Lord Nidimmud,

Your mother is Ninti, the queen of the sacred lake.

Ninkasi, your father is Enki, Lord Nidimmud,

Your mother is Ninti, the queen of the sacred lake.You are the one who handles the dough [and] with a big shovel,

Mixing in a pit, the bappir with sweet aromatics,

Ninkasi, you are the one who handles the dough [and] with a big shovel,

Mixing in a pit, the bappir with [date] - honey,You are the one who bakes the bappir in the big oven,

Puts in order the piles of hulled grains,

Ninkasi, you are the one who bakes the bappir in the big oven,

Puts in order the piles of hulled grains,You are the one who waters the malt set on the ground,

The noble dogs keep away even the potentates,

Ninkasi, you are the one who waters the malt set on the ground,

The noble dogs keep away even the potentates,You are the one who soaks the malt in a jar,

The waves rise, the waves fall.

Ninkasi, you are the one who soaks the malt in a jar,

The waves rise, the waves fall.You are the one who spreads the cooked mash on large reed mats,

Coolness overcomes,

Ninkasi, you are the one who spreads the cooked mash on large reed mats,

Coolness overcomes,You are the one who holds with both hands the great sweet wort,

Brewing [it] with honey [and] wine

(You the sweet wort to the vessel)

Ninkasi, (...)(You the sweet wort to the vessel)The filtering vat, which makes a pleasant sound,

You place appropriately on a large collector vat.

Ninkasi, the filtering vat, which makes a pleasant sound,

You place appropriately on a large collector vat.When you pour out the filtered beer of the collector vat,

It is [like] the onrush of Tigris and Euphrates.

Ninkasi, you are the one who pours out the filtered beer of the collector vat,

It is [like] the onrush of Tigris and Euphrates.

Conclusion

The hymn was most likely sung while the ancient Sumerians brewed their beer and was passed down by master brewers to their apprentices. Beer was valued highly in ancient Mesopotamia and an expert brewer would have lived quite comfortably once the brew was manufactured commercially. Even before that time, however, even a home-brewer could have made a comfortable living trading fine beer for other items. Bertman highlights this in quoting the Sumerian proverb which maintains, "He who does not know beer, does not know what is good" and how there were over 70 varieties of beer in Babylon alone (292).

Beer was consumed daily, as noted, but in great quantities at religious festivals and celebrations. Orientalist Samuel Noah Kramer notes how "beer had its divine and sublime qualities for the Sumerian poets and sages" and was, as noted, the drink of the gods (111). Ninkasi's name literally translates as "the lady who fills the mouth" and beer was thought to have healing and elevating qualities which could only improve one's life.

Kramer writes, "although she was the goddess `born in sparkling-fresh water', it was beer that was her first love" (111). Ninkasi's love of beer, and attention to her craft, provided the drink of the gods to mortals and still does so in the present day. Bertman writes:

Using the details of the brewing process recorded in this hymn, in 1989 the Anchor Brewing Company of San Francisco duplicated the recipe. According to one expert, the beer dubbed Ninkasi "had the smoothness and effervescence of champagne and a slight aroma of dates" which had been added as an ancient sweetening agent. (292)

In 2006, the Ninkasi Brewing Company, producing highly respected, premium beer, was founded in Eugene, Oregon, USA by Jaimie Floyd and Nikos Ridge; proof that Ninkasi's name, and her product, are still as relevant and popular today as they were in ancient Mesopotamia.