The Industrial Revolution saw a wave of technological and social changes in many countries of the world in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it began in Britain for a number of specific reasons. Britain had cheap energy with its abundant supply of coal, and labour was relatively expensive, so inventors and investors alike were lured by the possibility of profit if machines could be made that ran on coal and saved labour.

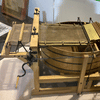

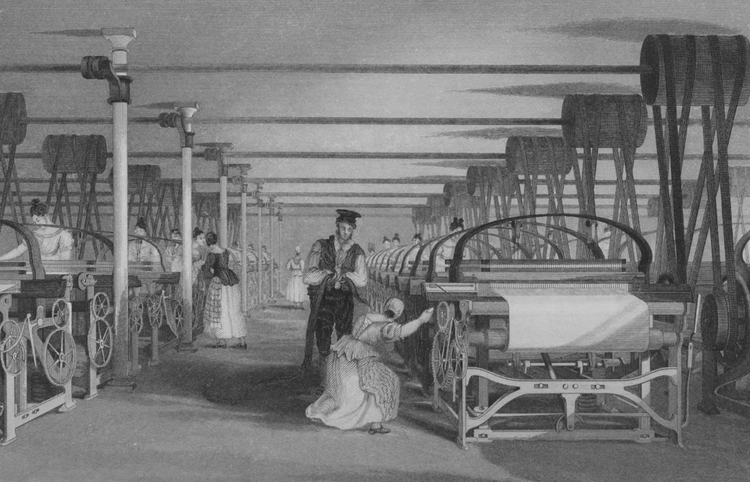

In the Industrial Revolution the steam engine first powered pumps in mines. Steam power allowed machines like the power loom to replace costly skilled labour and massively increase textile production. Steam was used as the power source for trains and ships. Even in agriculture, devices like the threshing machine could now replace human labour. Mechanised factories replaced cottage industries and accelerated the rate of urbanisation. Whole towns developed around the major coalfields. Wages rose and new jobs were created, albeit very often less skilled work than before. Inhabitants of towns and cities then wanted manufactured consumer goods, as did markets abroad, and so the industrialisation process was perpetuated and accelerated. This process, with some variations, eventually happened in many countries, but Britain experienced it first.

The following factors were all present in Britain and explain why it experienced the Industrial Revolution first:

- efficient agriculture

- coal as a cheap fuel

- significant urbanisation

- high cost of labour

- intercontinental trade opportunities

- government support of business

- innovation and entrepreneurship

- venture capital investors

- new sales and marketing techniques

Before examining Britain, it is perhaps worth noting what industrialisation meant and what its timescale was in general. The Encyclopedia of the Victorian World defines industrialisation as follows:

Generic term for the economic and social processes by which a society shifts from an agricultural basis to a manufacturing basis dependent on modern machinery. In Britain the revolution was essentially over by the early years of the Victorian era, with a flourishing factory system in place, a large urban population at work, and a powerful capitalist class thriving. For the other western powers, however, the industrial revolution was just beginning. France underwent it after 1830, Germany after 1850, and the United States after 1865…Elsewhere – Russia, China, Japan, and what is now called the developing world – it would become a fact of life in the twentieth century. (235)

The Cost of Labour

The question, then, is: why was Britain the first to industrialise? The first area to examine in answering this question is the level of wages in Britain. The population of Britain rose dramatically in the 17th century, particularly in London and other cities. Only in the Netherlands was there similar urbanisation as there was seen in Britain in this period. Wages rose because the amount of arable land was fixed. Agriculture was obliged to become more efficient to meet the rise in population, both in the use of equipment and in organisation such as land enclosures which put communal land to farming uses. These two factors: urban growth and greater agricultural efficiency (what some historians have called an agricultural revolution) led to rising demand for labour, and so wages rose. An additional factor in the rise in the cost of labour was the necessity for landowners to attract labour and prevent it from relocating to the growing urban areas. This phenomenon was not the case in contemporary France, Italy, and Spain where wages and living standards were falling. Where wages were low, capital investment in machines was much less attractive, as the cost-savings of mechanising production would be far less or none at all.

A third factor in labour costs rising was intercontinental trade, which created more demand for goods and so labour. Britain had established colonies or trading centres in North America, the Caribbean, and in Bengal and other parts of India. Other European countries also had empires which gave trade benefits, but not all European countries did, notably Germany. Spain extracted great wealth from the Americas (less from trade and more from direct acquisition), but this proved detrimental to its own economy since the consequent hyperinflation meant that no manufacturing could ever be profitable there under those labour conditions. Britain made vast amounts of money from its colonial trade in raw materials, manufactured goods, and slaves. This money could be reinvested in new technology. Further, the British Empire grew to become a huge market for British-manufactured goods like machinery and textiles. Governments protected this trade by suppressing local competition, restricting the sales of certain goods to and by colonists, keeping out rival imperialist powers by force or the threat of it, and by blocking certain exports to Britain, such as Irish meat and dairy products.

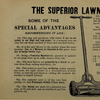

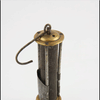

A Gallery of 30 Industrial Revolution Inventions

Once the cycle of industrialisation had begun and a consumer market was created, so high wages perpetuated the process, as here explained by the economic historian R. C. Allen:

High wages increased the supply of British technology as well as the demand for it. High wages meant that the population at large was better placed to buy education and training than their counterparts elsewhere in the world. The resulting high rates of literacy and numeracy contributed to invention and innovation. (137)

Innovation, Entrepreneurship, & State Support

Another reason for Britain's early industrialisation was the strong spirit of entrepreneurship. Unlike, say in France, where government sponsorship of inventions was usually limited to military purposes or a direct benefit to the state, in Britain, inventors of all kinds were encouraged by private investors. These were either business owners or those simply seeking a good return on a capital investment. The latter group were at the time called 'projectors'; today we would call them venture capitalists. The investors were looking for inventors who could create any means whatsoever to increase production efficiency and so profits. There were also some inventors who were self-funded and motivated by either the search for profit or to create a benefit for society or both.

Inventors were also helped by the state's policies of relatively low taxation (in this area but not others) and the fact that interest rates were lower in Britain, which meant loans could be more easily acquired for research and development. There was also a system of strong protection for patents. Consequently, inventors were encouraged. On the other side of the coin, governments significantly helped capitalists who might buy the inventions with restrictions imposed by acts of Parliament on worker rights (for example, to form trade unions or for skilled machinists to emigrate). At the same time, there was a relative openness of the state and inventors to ideas from anywhere, including abroad. Skills were brought in by immigrants that increased productivity, which was not always the case in some of the more closed and authoritarian European states of this period. Another factor in favour of Britain's industrialisation was its political stability which increased investor confidence. The combination of all of these various political and economic factors encouraged investors to take risks in new technologies and ride out any worker backlash to mechanisation, more so than in other countries.

The simplest way to increase profits was to increase the quantities of manufacturing or mining production and at the same time reduce the number of workers needed. Machines could achieve both of these aims. Once sizeable factories were established, more inventors were funded to find yet more cost savings, and so the industrialisation process spread deeper and wider. British inventors were not slow to imitate and improve upon inventions they came across in other countries either. Sometimes, a new technology appeared in countries where it was not fully exploited, for economic reasons or otherwise, but Britain's industrialisation often meant these innovations could work or work better in the economic environment of Britain. British engineers, in particular, became experts at developing and improving upon inventions first made elsewhere. Often called tinkering, it was this side of inventing that Britain excelled at rather than creating new machines from scratch.

Just as there was an environment of financial investment in new ideas, there was, too, a spirit of invention, or rather, an environment in Britain which somehow fostered new ideas and, more importantly, their fruition into practical reality. A traditional view is that "Newtonian Science, the Enlightenment and genius [were important] in providing knowledge for technologists to exploit, habits of mind that enhanced research, networks of communication that disseminated ideas, and sparks of creativity that led to breakthroughs that would not have been achieved by ordinary research and development" (Allen, 138). However, Allen points out that the genius of inventors in itself was not unique to Britain. As we have already noted, several other factors were necessary for genius to thrive and be useful to the industrialists who would take new ideas off the drawing board and put them onto the factory floor. In short, adoption promoted invention.

The industrialisation process was perpetuated by greater demand, which was driven by a rise in population, urbanisation, education, and consumerism. Conflicts like the Napoleonic Wars (1792-1815) also pushed innovation. Many British manufacturers (Josiah Wedgwood is perhaps the clearest example) were innovative pioneers in their use of sales and marketing tools, such as using touring salespeople, offering elegant showrooms, giving free samples to the rich and famous for endorsement, creating a range of products that reflected new tastes in fashion, and providing discounts and refund possibilities. All of these techniques together helped achieve more sales, which further drove production, which meant there was more capital to invest in yet more innovations in industrialisation.

Cheap Fuel

Inventing a machine was one thing, but having it run at a low cost was often quite another stage of development. A crucial factor in the question of whether machines could reduce production costs was the cost of the fuel they needed to run. Here Britain had a tremendous advantage over several other European countries (but by no means all). Britain was rich in coal. As a bonus, there were other natural resources of importance such as high-quality iron ore, lead, copper, and tin. Mining had been going on for centuries but had increased prior to the Industrial Revolution due to deforestation and the scarcity of wood. Coal became a cheap alternative to wood burning. It is no coincidence that many of the new cities growing up in Britain were near coalfields. These coalfields were all conveniently located near water for transportation, another great natural advantage Britain had.

The long history of mining in Britain meant that there was already the technological know-how of how to exploit minerals in the earth, which meant that when the new machines needed more coal than ever mined before, it was a question of increasing production rather than the more problematic issue of starting from scratch, as was the case in some other countries. Once again, when the first machines, usually steam engines, were in place and working, this encouraged further technological development to make them even more fuel-efficient and so, again, increase profits.

The mines accelerated both the growth in urbanisation and the rise in labour costs. In addition, cheap fuel often more than compensated for the high British labour costs and so meant that exports could be competitive.

Conclusion

In summary, then, several European countries had the advantages that Britain enjoyed in terms of creating a platform on which could be built a rapid process of industrialisation, but only Britain enjoyed all of the necessary, or most beneficial factors together. Some countries had trump cards. There was more gold in Spain, more coal in Germany, greater urbanisation in the Netherlands, and so on, but, overall, Britain had the winning hand in just where in the Western world industrialisation would take off. Then, once the wheels of industrialisation had started turning, more innovation meant they soon turned even faster, leaving behind most of Britain's European and North American rivals until they caught up later in the 18th or even 19th century. From around 1750 to 1850, the British were, it seems, justified in calling their island the workshop of the world.