The Battle of Lodi (10 May 1796) was a minor, yet important, engagement during Napoleon's Italian Campaign of 1796-97. Although the battle itself held little military significance, victory at Lodi gave General Napoleon Bonaparte the respect and loyalty of his men, who nicknamed him "the Little Corporal", and instilled in him the notion that he was destined for greatness.

The battle was fought between Bonaparte's Army of Italy and the rearguard of the Austrian army as it retreated across the Adda River. The French stormed the bridge over the river, charging into a hail of enemy canister shot, and won the day. Only five days after the battle, Bonaparte triumphantly entered Milan, the capital of Austrian Italy. Little more than a skirmish, the battle was of minor importance, since the Austrians had already been in full retreat and Bonaparte would have gained access to the bridge if he had only waited. Yet the heroics of the French army made the Battle of Lodi perfect fodder for propaganda back at home and helped Bonaparte capture the imaginations of French citizens. The victory won Bonaparte the love and respect of his soldiers and caused him to realize his "first spark of high ambition" that would ultimately lead him to his role as emperor of the French (Chandler, 84).

Soldiers of Liberty

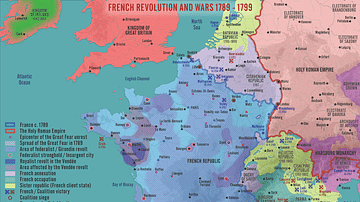

On 28 April 1796, after only a few weeks of campaigning, General Napoleon Bonaparte knocked the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia out of the War of the First Coalition (1792-1797). It was an astonishing victory for the young General Bonaparte, still only 26, and his daring Army of Italy. Barely a month earlier, Bonaparte had arrived in Italy to take command of what had been a ragged, undersupplied, diseased, and demoralized army less than 40,000 strong. He whipped it into good enough shape so that by the time the campaign opened on 10 April, it was able to attack with lightning speed; Bonaparte and his Army of Italy won three battles in three days over the Austrian and Piedmontese armies at Montenotte (12 April), Millesimo (13 April), and Dego (14 April). The French succeeded in driving the Allied armies apart during those battles, and Bonaparte decided to divide and conquer. He invaded Piedmont and decisively beat the Piedmontese army at the Battle of Mondovì (21 April). With the road to their capital of Turin wide open, the Piedmontese had no choice but to sue for peace, leaving the Austrians to fend off Bonaparte's relentless onslaught alone.

The armistice was signed at Cherasco, where the defeated King Victor Amadeus III was forced to agree to terms almost as humiliating as the defeat itself; along with allowing the French army free access to travel within Piedmont, he was obliged to hand over Alessandria, Coni, and Tortone to the French Republic. In the final peace treaty, signed a few weeks later, he was also forced to cede Nice and the Duchy of Savoy to France (although these territories were both already under French occupation). Such a rapid and complete victory had been the work of the soldiers of the Army of Italy, a fact that Bonaparte did not hesitate to remind them of in a proclamation circulated throughout the army:

Soldiers! In fifteen days, you have gained six victories, taken 21 colors and 55 pieces of artillery, seized several fortresses and conquered the richest parts of Piedmont. You have captured 15,000 prisoners and killed and wounded more than 10,000…you have won battles without cannon, have crossed rivers without bridges, made forced marches without boots…only the ranks of Republicans, the soldiers of liberty, are capable of suffering what you have suffered.

(Chandler, 76; Blanning, 151)

Given a taste of victory, Bonaparte hoped his men would thirst for more. The ink on the Armistice of Cherasco was not yet dry when the French general turned his attention to the Austrian army that still stood between him and Milan, the capital of Austrian Italy. The Austrians were in poor spirits, demoralized and depleted by their recent setbacks. Indeed, the Austrian commander, General Johann Beaulieu, had reported back to Vienna that his army was in a "very bad situation" (Chandler, 77). Hoping to move his army to better ground to regroup, Beaulieu announced his intention to withdraw to the north bank of the Po River, which offered an excellent defensive position.

This was something that Bonaparte needed to prevent if he was to force Beaulieu into a decisive battle on his own terms. Even as he was finishing negotiating the armistice with Piedmont, Bonaparte sent a division under General Amédée Laharpe to Acqui to forestall the Austrian river crossing. At the same time, Bonaparte wrote a letter back to the French Directory in Paris, reassuring the government that he would "catch up with the Austrians and beat them before you have time to reply to this letter" (Chandler, 77). However, Laharpe was delayed when a sudden mutiny broke out amongst his troops; by the time he restored order and made it to his destination on 30 April, most of the Austrian army was already across the river.

Crossing the Po

This left Bonaparte in a difficult situation. To get to Milan, he needed to cross the Po, but because the Austrians had crossed first, they now controlled the river crossings. Bonaparte knew he could not wait, since every day he delayed was another day the Austrians could use to reinforce their army and shore up their defenses in northern Italy. The only decision left to make was where to make the crossing. In this regard, Bonaparte had three viable options. The first, and most obvious choice, was the crossing at Valenza; this was closest to Bonaparte's current position but was also closest to the bulk of the Austrian army on the other side. Any attempt to cross here would be met with fierce resistance and would likely result in heavy French casualties. The second option was to cross just south of Pavia, which would place the French in the rear of the Austrian army. But this, too, was risky, as the Austrians would probably be watching this location closely as well. The third option was to cross at Piacenza, 80 km (50 mi) away; although this had the benefit of being far away from the Austrian defenses, Bonaparte would have to move quickly if he wanted to maintain the element of surprise.

Bonaparte opted for the Piacenza crossing and hatched a plan to keep the Austrians distracted from his true objective. As part of the armistice of Cherasco, Bonaparte had negotiated a 'secret' clause allowing him to use the bridge at Valenza. The Piedmontese leaked this information to the Austrians, who were now closely guarding that crossing. Bonaparte had been counting on this and, to make the illusion more believable, he sent two divisions under generals Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier and André Masséna to Valenza and ordered them to act like they were preparing to cross. Meanwhile, General Claude Dallemagne was given command of 3,500 grenadiers and 2,500 cavalry and was ordered to make a rapid march to secure the crossing at Piacenza; once Dallemagne had crossed the Po, the rest of Bonaparte's army would follow.

The plan was put into motion on 5-6 May. While Beaulieu was distracted by Sérurier and Masséna at Valenza, Dallemagne covered the 80-kilometer (50-mile) march, with Laharpe's division following close behind. At 9 in the morning on 7 May, Dallemagne reached Piacenza and crossed the Po; the daring Colonel Jean Lannes, a future marshal of the empire, was the first Frenchman to set foot on the north bank. As Dallemagne went to work securing the bridgehead on the north bank, he unexpectedly encountered a division of 4,000 Austrians led by General Anton Liptay, who had been sent by Beaulieu to keep an eye on the eastern crossings. The two sides skirmished throughout the day until the arrival of Laharpe forced Liptay to pull back to the town of Fombio. Beaulieu received word of the skirmish around dusk. Realizing he had been tricked, he sent 4,500 Austrians to reinforce Liptay and decided to begin withdrawing the rest of his army toward the Adda River.

On the morning of 8 May, Dallemagne and Laharpe stormed Fombio and routed Liptay's force. For two hours, the French pursued the Austrians, until they came to the town of Codogno where they ran into the reinforcements sent by Beaulieu. Fighting in the town continued well after sunset, and General Laharpe was killed, accidentally shot by his own troops in the confused nighttime action. The loss of the division commander dealt a heavy blow to French morale, and the men were on the point of retreating when Bonaparte's chief of staff, Alexandre Berthier, arrived with two additional demibrigades and took command of the battle. Berthier's presence gave the French a second wind, and they pushed the remaining Austrians out of Codogno at dawn on 9 May. The rest of the French army was now able to cross the river and when the last elements of Sérurier and Masséna's divisions were across, Bonaparte set out in pursuit of Beaulieu.

Battle of Lodi

General Beaulieu, meanwhile, was in the process of getting his army over the Adda River. For his crossing point, he had chosen the small town of Lodi; situated on the west bank of the Adda, Lodi was 32 km (20 mi) southeast of Milan. It featured a long, narrow bridge over the river that was 180 meters (200 yd) long and 9 meters (10 yd) wide. By the early morning of 10 May, most of the Austrian army had already crossed the Adda, though 9,500 men under General Karl Sebottendorf remained behind as a rearguard. Three of Sebottendorf's battalions, along with a dozen cannons, defended the bridge of Lodi and the causeway leading up to it; six of the cannons were placed on the eastern side of the bridge, while the other six guns were placed on each side of the roadway to cover it with fire.

This was the situation at Lodi when Dallemagne's advance guard arrived sometime before 9 a.m. A hussar regiment under Auguste de Marmont and a battalion of grenadiers under Colonel Lannes were enough to clear out the remaining Austrians from the town itself, but their spirited assault was halted at the bridge, where the French were greeted with a hail of canister shot. The advance guard was forced to pull back to the town, where it waited for several hours for the rest of the French army to catch up. When General Bonaparte arrived, he wasted no time setting up 24 cannons along the west bank of the Adda and sent detachments of cavalry along the river to search for a ford. As the French were organizing themselves, the Austrians attempted to destroy the bridge, but each time they tried, they were chased away by French artillery fire.

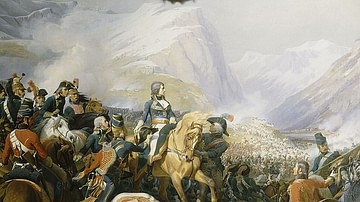

Unless a ford could be found, Bonaparte knew he had to storm the bridge. If he waited, he would lose the chance of beating Beaulieu's army before it could reinforce Milan. During the afternoon, Bonaparte ordered the artillery to double its rate of fire and gathered 3,500 grenadiers in the streets of Lodi. After an inspirational speech, he urged them on to charge the bridge; one company of carabiniers under Colonel Pierre-Louis Dupas requested the near-suicidal honor of leading the charge. Such was an example of the impact that patriotic speeches and military pride had on the soldiers of Republican France.

The French attack began at 6 p.m. Colonel Dupas' carabiniers stormed onto the bridge with shouts of "Vive la Republique!" and were met with a wave of canister shot. Scores of men were ripped to pieces by the Austrian cannons, but as the bridge became littered with corpses, the French pushed on; some soldiers jumped into the water and began firing up at the Austrian gunners from the shallows. This first wave made it halfway across the bridge before the momentum was lost and it was forced to pull back. Yet the bravery of this first attack greatly inspired the rest of the French army. As soon as the French column made it back to the safety of the west side of the river, it was rallied by some of the most senior French officers including Berthier, Masséna, Lannes, and Dallemagne, who pushed their way to the front and led the men back onto the bridge.

This second wave proved unstoppable. Again, the Austrian cannons shredded bloody holes through the French swarm, but this time the French did not stop at the center of the bridge. More French sharpshooters had waded beneath the bridge and were picking off the Austrian gunners, which eased the relentlessness of the Austrian suppressing fire. The French made it to the eastern side of the bridge and overwhelmed the Austrian cannons, establishing a bridgehead. General Sebottendorf managed to rally his men and launch a fierce counterattack that almost succeeded in recapturing the bridge. However, additional French soldiers from Masséna's and Augereau's divisions came pouring across the river to assist the grenadiers. The decisive moment came when a body of French cavalry appeared on the Austrian flank; at long last, they had found a ford. Sebottendorf broke off the attack and withdrew to rejoin Beaulieu's army. The Austrians had lost some 153 killed, 182 wounded, and 1,701 captured, and had lost 16 guns as well. The French had suffered around 350 casualties.

Aftermath & Legacy

It turned out that Beaulieu was not, in fact, heading for Milan. With only 25,000 battle-ready men, most of them starving and in poor spirits, he lacked the numbers and resources to defend it. Instead, he continued retreating toward the fortress of Mantua. Consequently, Bonaparte and the Army of Italy entered Milan uncontested on 15 May, only five days after Lodi. The heart of Austrian Italy was now in French hands. Bonaparte extorted the Milanese for 2,000,000 francs and priceless works of art, which he used to pay his soldiers. He reformed the city's administration and oversaw the drafting of a new constitution before leaving Milan in June to continue his campaign against the Austrians. It would take another year and a string of further battles before Bonaparte finally brought the Austrians to the negotiating table at Loeben in April 1797.

The Battle of Lodi, therefore, did not have to be fought at all. Beaulieu had already been in full retreat before the battle and continued to retreat when it was over. Bonaparte failed in his objective to force Beaulieu to fight a decisive battle, but he occupied Milan anyway, something that likely would have happened in a similar manner had he not attacked the Austrian rearguard at Lodi. Yet despite all this, the 'Bridge of Lodi' became an important piece of propaganda, a symbol of French Republican glory. The image of the fearless charge across the bridge became imprinted in the imaginations of patriotic Frenchmen everywhere, and the officers who led that charge were soon to become famous. "Immortal glory to the conqueror of Lodi," the French Directory declared in a proclamation on 21 May, "Honor to the commander-in-chief, honor to the intrepid Berthier, who thrust himself to the head of this redoubtable and formidable republican column…honor to Generals Masséna, Cervoni…" (Blanning, 147).

As medallions commemorating the victory were being minted in Paris, the victory at Lodi became mythologized even to the French soldiers who had fought in it. During the battle, Bonaparte had proven himself to be not just their commander but one of them – the general had personally lent a hand in arranging the cannons on the banks of the river, exposing himself to enemy fire in the process. This earned him the everlasting respect and admiration of his men, who gave him the affectionate nickname of "the Little Corporal". There were no more whispers of mutiny after Lodi, and the soldiers of the Army of Italy followed their little corporal with eagerness during the rest of the campaign, and in some cases, beyond.

Finally, the battle had an impact on the psyche of General Bonaparte himself. Much later, Bonaparte would claim that it was at Lodi that he realized that he was destined for greatness:

I no longer regarded myself as a simple general, but as a man called upon to decide the fate of peoples. It came to me then that I really could become a decisive actor on our national stage. At that point was born the first spark of high ambition. (Roberts, 91)

Whether this was an early sign of Bonaparte's infamous egomania or a true recognition of his talents, Bonaparte became increasingly confident after Lodi. He refused a request from the Directory to split command of the Army of Italy with General Kellermann, threatening to resign if he was forced to; unwilling to risk losing France's most successful general, the Directory backed down. Victory at Lodi preceded victory in Italy, and Bonaparte was soon one of the most popular public figures in France. He would use that popularity to seize control of the government during the Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799, which would in turn lead to his reign as emperor of the French.