The Battle of Rivoli (14-15 January 1797) was the climactic battle of Napoleon's Italian Campaign of 1796-97. A fourth and final attempt by the Austrian army to relieve the siege of Mantua was thwarted by Napoleon Bonaparte's Army of Italy at Rivoli. The French victory led to the fall of Mantua and the evaporation of Austria's control of northern Italy.

On the Verge of Victory

In late November 1796, as the War of the First Coalition dragged on into its fifth winter, the weary combatant nations were eager to make peace. General Henri Clarke, representing the French Republic, visited Vienna to negotiate with the Austrian emperor Francis II; the French had become so tired of war that Clarke was instructed to agree to a compromise peace should the opportunity arise. Shortly after he arrived in the Austrian capital, Clarke received a letter from General Napoleon Bonaparte, his former subordinate at the Topographical Bureau who was now leading the French army in Italy. Bonaparte told Clarke that the fortress of Mantua was on the verge of falling into French hands and that the Austrians were about to be kicked out of Italy. Since he was so close to succeeding, Bonaparte asked Clarke not to make any concessions regarding Mantua during negotiations. Clarke believed Bonaparte, and so, when the Austrians began negotiations by demanding the right to reprovision the fortress while the talks were in progress, Clarke refused; negotiations promptly broke down.

It is quite interesting that peace negotiations broke down over the situation on the Italian theatre of war which, less than a year before, had been considered only a sideshow to the larger campaigns in Belgium and Germany. Such was a testament to the triumphs of General Bonaparte himself; only 27 years old, Bonaparte had whipped the ragged and undersupplied Army of Italy into shape, kicked the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia out of the war, captured Milan, and defeated the Austrians in several key engagements such as the Battle of Lodi (10 May 1796), the Battle of Castiglione (5 August) and, most recently, the Battle of Arcole (15-17 November). Now, Bonaparte's victorious army sat outside the walls of Mantua, continuing a crucial siege that had been ongoing since June. Mantua was part of the Quadrilateral, a series of four fortresses that guarded the Alpine passes and the entrances to the Po River and Lake Garda. Should it fall, the Austrians would lose their last foothold in northern Italy, and the road to Vienna would lie wide open to Bonaparte's army.

Yet the situation at Mantua was less optimistic than Bonaparte had made out in his letter to Clarke. True, the garrison was on the verge of falling; of the 18,500 Austrian soldiers in the Mantua garrison, only 9,800 were currently fit to fight, the rest incapacitated by wounds, disease, or malnutrition. Since September, over 9,000 Austrian soldiers had died in Mantua alongside thousands of civilians. The last rations were scheduled to run out on 17 January, and the garrison was already reduced to eating rats and horseflesh. This would have been an ideal situation for any besieging army, had there not also been an Austrian army sitting on the Brenta River, reinforcing itself by the day, waiting for the moment to pounce on Bonaparte and set Mantua free.

This Austrian army was commanded by Hungarian General József Alvinczi, who had come close to decisively beating Bonaparte earlier that month before suffering a defeat of his own at Arcole. Alvinczi, who Bonaparte would later refer to as his most formidable opponent during the entire Italian campaign, was preparing to launch a fourth attempt to relieve the siege of Mantua, in the understanding that should he fail, there would likely be no opportunity for a fifth try. Bonaparte, too, understood that Alvinczi was not about to sit idly by and allow Mantua to fall, and he busied himself with preparing for the coming attack.

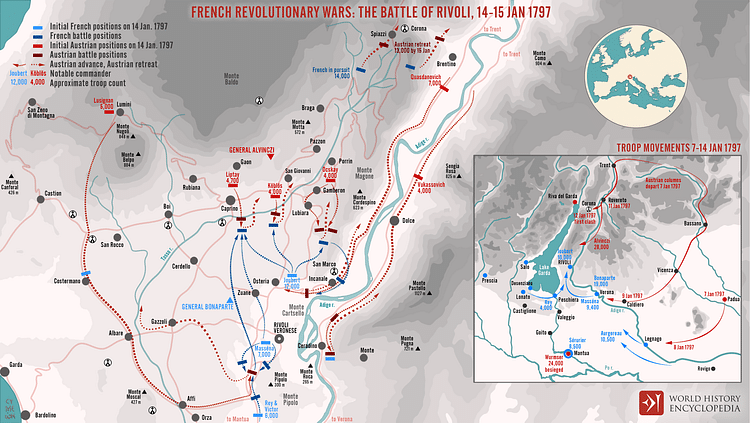

A series of field fortifications were dug at the likely points of attack such as at La Corona and Rivoli on the east side of Lake Garda, which were being held by a division under the daring young General Barthélemy Joubert. Joubert was supported by the division of General André Masséna at Verona, with General Pierre Augereau's division guarding the lower reaches of the Adige River. In total, Bonaparte had about 34,500 men with which to fend off the Austrians, and another 10,000 under General Jean Sérurier to maintain the siege of Mantua itself; by contrast, Alvinczi had about 46,000 men. Such was the situation in Italy as the year 1796 came to a close.

The Austrians' Fourth Attempt

In early January 1797, Alvinczi realized he could delay his offensive no longer. He drew up a plan of attack that required he split his army into two forces, just as he had done during the Arcole campaign. 15,000 men, under the command of General Giovanni di Provera, were to march east to threaten the French defenses at Verona and along the Adige. The hope was that Provera could distract Bonaparte long enough for Alvinczi, at the head of the remaining 28,000 troops, to march south along the east coast of Lake Garda, swat aside Joubert's French division at La Corona, and continue down to rescue the garrison at Mantua.

On 7 January, the Austrian offensive got underway. Alvinczi, who had spent the previous weeks amassing his men at the top of Lake Garda, began his march down the lake's eastern side. Meanwhile, a column of 9,000 Austrians from Provera's force attacked French General Augereau's division at Legnago along the Adige River. The next day, the rest of Provera's men, about 6,200, struck at Verona. Provera seemed to be probing the French defenses in preparation for a larger attack, and on 11 January, Bonaparte rushed into Verona to assess the situation. Immediately, he realized something was wrong; the main part of the Austrian army was nowhere to be seen, leaving Bonaparte to wonder where the main attack would fall. On 12 January, he received a report that Joubert's men had also skirmished with some Austrian detachments at La Corona; Bonaparte's letter to Joubert on the 13th exemplified his uncertainties:

Let me know as soon as possible whether you consider the enemy on your front to number more than 9,000. It is vitally important that I should know whether the attack being made upon you is serious…or merely a secondary affair designed to put us off. (Chandler, 115)

Joubert's reply, which came at 3 p.m. that same day, confirmed Bonaparte's suspicions: Joubert had been overwhelmed by a superior Austrian force and had been forced to pull back to Rivoli. Realizing that Provera's attacks were merely feints, Bonaparte wrote to Joubert, ordering him to hold his ground at Rivoli at all costs. Meanwhile, he gathered what troops he could spare, consisting of 22,000 men mostly from the divisions of Masséna and General Venance Rey, and set out for Rivoli. He left 8,000 men to continue the siege of Mantua, 3,000 to hold Verona, and Augereau's division to guard the Adige crossings.

Battle Plans

The Austrians had been slow to follow Joubert from La Corona for several frustrating reasons. For one thing, it was difficult to move quickly over the terrain, which lacked sufficient quality roads, and for another, Alvinczi's incompetent quartermasters had failed to stock the army with enough rations. Therefore, by the time the Austrians arrived at Rivoli, Joubert's division already occupied the Trambasore Heights, an excellent defensive position that sat between the Adige and Tasso rivers in the shape of a horseshoe. Alvinczi was now faced with the difficult task of dislodging Joubert from the heights before French reinforcements had time to arrive. His plan was to split his army into six columns. The first three, consisting of a combined 12,000 men and commanded by generals Liptay, Koblos, and Ocskay, were to launch a frontal assault on the north side of the heights. These columns could not expect artillery support since the lack of roads prevented Alvinczi from bringing up his cannons.

A fourth column under the Spanish-born Austrian general Marquis de Lusignan was to swing wide around the west and outflank the French army, cutting off their line of retreat and preventing French reinforcements from joining the fight. A fifth column under General Vukassovich was to advance down the Adige River and establish artillery batteries on the banks. The sixth column of 7,000 men under General Peter von Quasdanovich was given the most important job: moving along the Monte Magnone ridge, Quasdanovich was to enter the Osteria gorge which would allow him to get behind the French lines. Overall, it was a complex plan that relied on speed and coordination, two things that were decidedly not the strong suits of the Habsburg army.

Bonaparte rode ahead of his men and arrived at Rivoli at 2 a.m. on Saturday, 14 January. In the small hours of the morning, he and Joubert surveyed the French positions, aided only by moonlight. It soon became apparent that the French would need to take possession of San Marco and the Osteria gorge; at 4 a.m., a single brigade under General Honoré Vial occupied these positions after meeting minimal Austrian resistance. With Joubert's 10,000 men positioned on the east side of the Trambasore Heights, Bonaparte realized victory would depend on how quickly the rest of his army could arrive on the field. At 6 a.m., the first elements of General Masséna's division arrived. Half of Masséna's division was sent to occupy the west side of the heights, the rest were held in reserve around Rivoli itself.

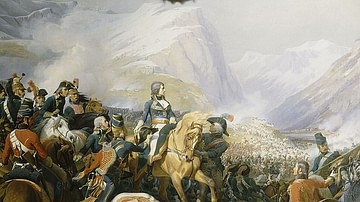

Battle of Rivoli

The battle began at dawn when Joubert's division advanced forward to drive the first three Austrian columns back. Supported by 18 heavy guns on the ridge, Joubert's attack was initially successful as his men captured the hamlet of San Giovanni. However, General Koblos' second Austrian column unexpectedly held its ground, checking Joubert's advance; on the left side, Liptay's first Austrian column found its courage and attacked Joubert's flank. Almost immediately, the French 85th demibrigade panicked and fled. Joubert's entire line was in danger of crumbling before Bonaparte sent in part of Masséna's reserve. It was enough to plug the line and prevent a rout. Fighting here, at the center of the battlefield, would continue for ten grueling hours.

At 9 a.m., Vukassovich had assembled batteries on the opposite side of the Adige. These guns gave covering fire for Quasdanovich's column which forced the French out of the critical village of San Marco and occupied the Osteria gorge. Two hours later, the 5,000 Austrians under the Marquis de Lusignan appeared along the ridge to the south of Rivoli, cutting off the French line of retreat. The French were boxed in on all sides; Bonaparte had only one brigade left in reserve and reinforcements under General Rey were still an hour away. When his anxious officers informed him that the Austrians had the French surrounded, Bonaparte remained stoically calm, replying simply, "We have them now" (Roberts, 127).

Springing into action, Bonaparte turned to the 18th demibrigade of Masséna's division, which had recently arrived on the battlefield from Lake Garda. He tasked this unit with attacking Lusignan's column and reopening the French line of retreat. He roused them to action with one of his signature battlefield speeches: "Brave Eighteenth! I know you; the enemy will not stand before you" (Chandler, 118). As the 'Brave Eighteenth' charged off toward Lusignan, Bonaparte turned all his attention toward Quasdanovich, who was pouring more troops into the Osteria gorge. Since he had run out of reserve units, Bonaparte made the calculated risk to thin out Joubert's line in the center of the battle; every soldier who was not needed to pin down the first three Austrian columns was to go and join the fight to retake Osteria and San Marco.

These French soldiers swiftly formed a human dam, keeping Quasdanovich from breaking out of the gorge. Bonaparte was quick to take advantage of the situation; aiming light artillery at the mass of Quasdanovich's men, he hit them with canister shot at point-blank range. As the bursts of shrapnel tore the Austrians to shreds, a lucky shot hit two Austrian ammunition wagons, causing a large explosion that resulted in panic. Bonaparte then ordered his men to charge with fixed bayonets, which did the trick of clearing the gorge of any living Austrian soldiers; only the dead and dying remained.

By attacking first Lusignan and then Quasdanovich, Bonaparte had deflected the most immediate threats to his army and could now turn his attention back to the first three Austrian columns. The soldiers who had just recaptured the gorge were given no time to rest and were rushed back into the brutal fray that had been ongoing in the center of the battlefield. At around midday, the French cavalry under General Joachim Murat arrived and slammed into the center Ocskay's column; this turned the tide, and the mass of Austrian troops in the center began to gradually retreat to the positions they had started at that morning. Meanwhile, General Rey's division finally arrived and joined the battle against Lusignan, who held out for as long as he could but was soon forced to retreat, losing 2,000 prisoners in the process. By 2 p.m., the Austrians were in full retreat; there was no question that the French had won the day.

The Fall of Mantua

The next day, 15 January, saw continued fighting; only Lusignan's column had been fully destroyed, leaving five more Austrian columns as potential threats. But Joubert, feeling confident after his division's performance the day before, attacked the first three Austrian columns, sending them running back to La Corona with the help of Murat's cavalry. Following this additional humiliation, Alvinczi ordered a retreat over the Adige, and the Battle of Rivoli was over. The French had lost around 2,200 killed and wounded and 1,000 captured, but the Austrians had fared worse, losing 4,000 men killed and wounded, 8,000 men captured, and 8 guns and 11 colors also captured.

Though Alvinczi had been soundly defeated, the threat was not quite over. While most of the French army had been occupied at Rivoli, General Provera was busy marching his corps rapidly toward Mantua. At noon on 15 January, he arrived at La Favorita, a village outside Mantua, and faced off against the 8,000 French under General Sérurier, who Bonaparte had left behind to maintain the siege. The sight of Provera's corps inspired the starving Mantua garrison to sally out at daybreak on 16 January, but Sérurier held them back, forcing them back inside the fortress. In the afternoon, Bonaparte arrived and attacked Provera in the rear. Sandwiched between Bonaparte and Sérurier, Provera wisely chose to surrender rather than to see his men needlessly massacred.

Thus, the fourth and final attempt by the Austrians to relieve the siege of Mantua came to an end. On 17 January, Mantua ran out of food; the garrison managed to hold out for two weeks longer before the fortress' commander, Field Marshal Dagobert von Wurmser, agreed to capitulate on 2 February. The nine-month siege was finally over, having cost the lives of over 16,000 Austrian defenders and thousands of unfortunate civilians. After capturing the fortress' 325 cannons, Bonaparte allowed Wurmser and his officers the honors of war and let them return to Austria; the rank-and-file defenders were sent to France as prisoners of war.

The French victory at Rivoli and the subsequent fall of Mantua completed the French conquest of northern Italy, as the last Austrian soldiers in the region retreated across the Alps. Although France celebrated the conquest, Bonaparte did not rest to bask in his triumph; as soon as Mantua fell, he invaded the Papal States, inducing the hapless Pope Pius VI to formally cede Romagna, Bologna, Avignon, and Ferrara to France and to pay the French a hefty annual tribute of 30 million francs. With central Italy secured, Bonaparte marched his army through Tyrol and made it within 160 kilometers (100 mi) of Vienna. On 2 April 1797, the Austrians sued for peace, and an armistice was signed at Leoben; this was followed by the Treaty of Campo Formio, which was finalized on 17 October and brought the War of the First Coalition to an end.