At the dawn of the French Wars of Religion (1562-1598), Montpellier in southern France had a significant Protestant minority that controlled the city's institutions. The Edict of Nantes in 1598 ended the wars and Protestants retained territorial possession of Montpellier as a fortified city. The city returned to Catholic control under the terms of the Peace of Montpellier after a long siege in 1622 led by Louis XIII of France (r. 1610-1643).

Early History of Montpellier

The region of Montpellier is an ancient land of settlement and passage where Phoenicians, Greeks, Iberians, and Celts left an imprint. Roman domination and influence began in 123 BCE when Languedoc became a Roman colony. The Roman general and senator Gnaeus Domitius (d. c. 104 BCE) left his mark on the country by creating the road that bears his name, the Via Domita. This east-west axis structured the exchanges and the life of the region by uniting Italy to Spain. Montpellier was founded in 985, and strategically located on the Roman road. William I of Montpellier received an agricultural estate from the Count of Melgueil that expanded under the house of Guilhem. Beginning in the early 11th century, the Lords of Guilhem became more powerful than the Counts of Melgueil. In 1156, William VII of Montpellier married a descendant of Hugo Capet (r. 987-996), Matilda of Burgundy. In 1174, William VIII of Montpellier married Eudokia, niece of the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Komnenos (r.1143-1180).

From William I to William IX, the last lord of the Guilhem dynasty from 1202 to 1204, Montpellier enjoyed a long period of peace and spectacular development. Through the marriage of Marie of Montpellier (l. 1182-1213), daughter of William VIII, to Peter II of Aragon (l. 1178-1213), the city was attached to the Spanish kingdom until its return to the Kingdom of France in the 14th century. In the 13th century, Montpellier became an important university and trading town. In 1289, a bull from Pope Nicolas IV established a university to which students came from afar to sit under renowned masters in a city open to the influences of Arab and Jewish scholars. With 35,000-40,000 inhabitants, Montpellier became the second largest city in France after Paris. Trade activity passed through Lattes, the city's port, and new ramparts united the seigniorial town of Montpellier with the episcopal city of Montpellier.

16th-Century Wars of Religion

City records dating to 1560 show the rapid progression of Protestantism among foreign university students and influential professors like Guillaume Rondelet (l. 1507-1566) and Jean Bocaud (l. 1511-1561). Protestants grew in strength and began seizing Catholic churches in 1561. They consolidated their power after the Edict of January in 1562, which granted religious tolerance to Protestants. The bishop and the governor fled the city. Monasteries and convents were pillaged and destroyed, and priests and nuns were expulsed from the city. Montpellier was shaken by these conflicts and torn politically between Catholics and Protestants. The nobility was also divided between the Catholic Church and the new religion. King Charles IX of France (r. 1560-1574) denounced the influence of the Reformed leaders, Louis I de Bourbon, Prince of Condé (l. 1530-1569), and Gaspard de Coligny (l. 1519-1572), Admiral of France. The former died at the Battle of Jarnac in 1569; the latter's assassination unleashed the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre in August 1572.

Following the massacre of Huguenots at Vassy in March 1562, the Reformed political party established a new organization to lead the war effort. The Huguenots held the cities of Rouen, Lyons, and Orléans, the latter taken by Condé on 2 April 1562. In Languedoc, Condé appointed Jacques de Crussol (l. 1540-1584) as leader of the Reformed party. Many Catholics were forced to flee the towns acquired by the Huguenots – Montpellier, Béziers, Nîmes, Uzès, Agde, and Beaucaire. Viscount Guillaume de Joyeuse (l. 1520-1592), lieutenant general of Languedoc, raised a Catholic army to reconquer the Hérault valley and seized Pézenas and Montagnac. In September, the army of Joyeuse camped before Montpellier and faced the army of Jacques de Crussol composed of contingents from Dauphiné and Provence. Both sides retreated after numerous skirmishes, and the Huguenots retained control of the city. Fearing a siege undertaken by Joyeuse, churches and convents were destroyed in the areas surrounding the city.

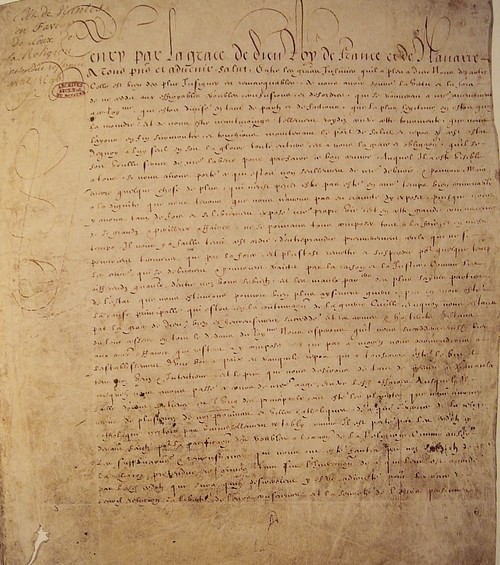

Edict of Nantes

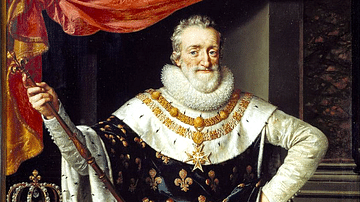

Henry IV of France and the Edict of Nantes in 1598 ended the armed conflict of the French Wars of Religion and established an uneasy coexistence. The application of this edict of pacification was complicated in many regions since the king's authority was limited in Protestant-controlled cities distant from Paris. The re-establishment of Catholic worship and festivals at Montpellier was met with resistance. At the request of the lieutenant governor of Languedoc, Henri de Montmorency (l. 1534-1614) and royal commissioners were sent in 1601 to mediate the execution of the Edict of Nantes. When Henry IV of France (r. 1589-1610) was assassinated in 1610, he was succeeded by his young son Louis XIII of France (r. 1610-1643) and his wife Marie de Medici (l. 1575-1642), who served as queen regent during her son's minority. Together they began to undermine the Edict of Nantes.

The Estates-General, composed of clergy, nobility, and commoners, gathered in 1614 and 1615. Protestants quickly perceived that the nobility and the clergy were prepared to consider the edicts of pacification as provisory. They were also alarmed by the proposed marriage of Louis XIII to Anne of Austria (l. 1601-1666). Three provinces, Languedoc, Guyenne, and Poitou took part in an uprising led by malcontent lords. Marie's negotiations with them resulted in the Treaty of Loudun in 1616, which granted six more years of protection for Protestant strongholds.

The presence of Protestant strongholds became intolerable for Louis XIII. Under him, the domination of the Catholic clergy grew rapidly. The king's new minister, Charles d'Albert, Duke of Luynes (l. 1578-1621), pledged to exterminate the heretics and launched a military campaign against the Huguenots. Cardinal Richelieu (l. 1585-1642) was prime minister from 1624 to 1642 during the reign of Louis XIII. He was a man of great ambition and capacities, a strict defender of the Catholic cause in France. Louis XIII, the Duke of Luynes, and Richelieu sought to force the submission of Protestants to royal authority and reinforce the unity of the kingdom.

Louis XIII's Military Campaigns

Louis XIII led a punitive expedition against Protestant Béarn in 1620 and broke the fragile religious peace in the kingdom. He ordered the restitution of possessions to the Catholic Church and reestablished Catholicism in Protestant regions. In response to the king's actions, in December 1620, the Huguenot general assembly at La Rochelle, a Protestant stronghold of the French Reformation, divided France into eight quasi-military regions with commanders from the nobility. Montpellier became the Huguenot capital of Languedoc with a Protestant minority in positions of power that provoked social tensions. Henry II, Duke of Rohan (l. 1579-1638) and cousin to Henry IV, rapidly became the leader of the rebellion. There were three religious wars from 1621 to 1629. The first war lasted from 1621 to 1622 and ended with the Peace of Montpellier. The last war ended in 1628 with the fall of La Rochelle in 1628 and the Peace of Alès in 1629.

In April 1621, Louis XIII and the Duke of Luynes led an army of 20,000 men against Saumur, the first Protestant stronghold to fall. The royal army continued south and in June 1621 met stiff Huguenot resistance at Saint-Jean d'Angély before its capitulation after a three-week siege. The next attack was against Clairac, a Protestant bastion in the Agenais region whose motto was "City without King, Soldiers without Fear." The city surrendered after twelve days of siege from 23 July to 4 August. As the king's campaign continued, Montauban endured three months of siege during which the royal army suffered the loss of 14,000 men and failed to breach the fortifications. Louis XIII lifted the siege and left on 14 November, a resounding victory for the Huguenots. In December, during the retreat of the royal army, the Duke of Luynes besieged, pillaged, and burned down the small town of Monheurt only to die during an epidemic.

The battles continued as Louis XIII confronted the Huguenot army in the marshes of the Isle of Ré in April 1622. The defeated Huguenots retreated to La Rochelle, and the king, profiting from this victory, easily took the port of Royan on 11 March. From Royan, the king marched on the small city of Négrepelisse in June. On 11 June, the garrison surrendered and the royal army massacred the entire population and soldiers as an example to other rebels. That same month Saint-Antonin-Noble-Val, where the Huguenot army had taken refuge, was besieged by Louis XIII. After violent combats, the rebels surrendered their arms.

The Siege of Montpellier

Louis XIII arrived in Bas-Languedoc early in July 1622 to prepare for the siege of Montpellier. The army began tightening its grip on the surrounding areas. Béziers, Bédarieux, Mauguio, Marsillargues, Sommières, and Aigues-Mortes all fell before the royal troops. Lunel offered the most resistance, and the battle ended in a bloodbath. Louis XIII presented himself before Montpellier on 30 August 1622 and camped on an elevated area overlooking the Valley of Lez. The siege of Montpellier began the next day and was met by a valiant defense. Together with 2,000 recruits from Languedoc, Rohan formed three regiments from the inhabitants of the city. Women brought food and ammunition, cared for the wounded, and engaged the enemy in battle. The city was protected by impressive fortifications of walls and moats and a line of terraced earthworks. For weeks on end, thousands of cannonballs rained down on the 4,000 inhabitants.

The king's troops concentrated their efforts on the north side of the city between the Pila-Saint-Gély and Carmes gates and dug trenches as close to the defenses as possible. The royal army with 20,000 infantrymen and 3,000 cavalrymen suffered heavy losses. Although each side tended to exaggerate the losses of the adversary, according to the Journal du Siège, there were more deaths among the besiegers, with death from disease ranked as the number one cause. Marked by the siege of Montauban the previous year and wanting to avoid another fiasco, the king negotiated an honorable surrender with the Duke of Rohan.

A truce was declared on 12 October after 40 days of intense bombardment. The former Protestant François de Bonne (l. 1543-1626), Duke of Lesdiguières, and two others negotiated in the name of the king with Rohan and deputies of the Cévennes, Uzès, Nîmes, and Montpellier. The articles of peace were accepted by the Huguenots on 18 October 1622, and Rohan personally visited Louis XIII's tent to request a pardon. The next day Protestant representatives kneeled before the king, who accepted their submission. That afternoon the Duke de Lesdiguières entered the city with 4,000 men. The city was demilitarized before the arrival of the king. Only two Protestant strongholds remained: La Rochelle and Montauban.

On 20 October, Louis XIII triumphally entered the city by the Lattes Gate. The king was welcomed with cries of "Long live the king!" and "Mercy!" One week later the king left the city leaving two regiments under the command of Lesdiguières with orders to demolish the walls built to withstand the siege. The Peace of Montpellier ended the first war of religion between Louis XIII and his subjects of the "so-called Reformed religion" (la religion prétendue réformée), a phrase which subsequently characterized subjects belonging to the Protestant confession. The siege left the Huguenot party weakened, and although the Peace of Montpellier was renewed in 1626, hostilities were reignited with the siege of La Rochelle in 1627.

Conclusion

Montpellier's capitulation marked the city's integration with the French monarchy, from a Huguenot bastion to the capital of Languedoc, faithful to the king and Catholicism. The peace signed between the two parties confirmed the Edict of Nantes, with a return to the religious status quo where political gatherings were forbidden without royal authorization. The Duke of Rohan was compensated for the loss of Poitou and Saint-Jean d'Angély. This favorable treatment led some in the Protestant camp to accuse him of treason.

Louis XIII returned to Paris in triumph with grand celebrations in cities along the way. The following year the king struck a commemorative medal to celebrate his victory. On the reverse side, the king is on horseback sword in hand in a warrior posture crushing his enemies. Four bourgeois are on their knees presenting the keys of the city. The Latin inscription reads: "Victorious by weapons and clemency." The fortifications of the city were demolished between November 1622 and November 1623. With the consular elections in February and March of 1623, Montpellier passed definitively under the control of royal authority and would no longer rise up against the king. Louis XIV and the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 outlawed the Reformed religion, and the Grand Temple was destroyed.