The celebration of Juneteenth – originally known as "Freedom Day" – began on 1 January 1866 in Texas and, since then, a number of myths have grown up around the event it commemorates: the issuance of General Order No. 3 in Galveston Texas enforcing the Emancipation Proclamation. Many of these myths are regularly repeated today, especially during Juneteenth events.

The myths do not detract from the importance of the celebration but do obscure the historical event it commemorates and seem to have evolved, as all legends do, through repetition without fact-checking. Some of these distortions seem to have already been accepted as truth by 1900, though it is difficult to pinpoint the time and place of origin, and have been repeated since. In June 2021, when Juneteenth was proclaimed a federal holiday in the United States, politicians routinely repeated several of these myths, notably numbers 1, 2, 8, and 9 below.

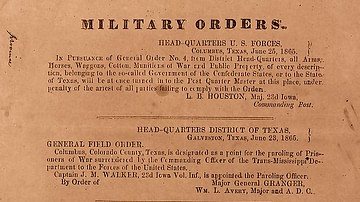

The purpose of this article is to clarify the historical event of 19 June 1865 when General Granger of the Union Army issued General Order No. 3 in Galveston, Texas announcing "all slaves are free" in accordance with the Emancipation Proclamation, which had been issued on 1 January 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation only addressed the institution of slavery in the Confederate States which were at that time at war with the federal government. The proclamation was issued to prevent England from entering the war on the side of the South because England, which had outlawed slavery, could not legally support the pro-slavery Confederacy after President Lincoln had proclaimed the Union's cause as a crusade to abolish the institution.

The Emancipation Proclamation did not free a single slave when it was issued and did not address the institution in the border states. The proclamation was only effective once Union troops had taken Confederate territories or, as they advanced, liberated slaves who were able to make it to their lines. After the American Civil War ended in April 1865, only then could the Emancipation Proclamation be enforced fully in the former Confederate States and, on 19 June 1865, General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston, Texas to announce this policy through General Order No. 3.

Much of the following information is taken from Juneteenth 101: Popular Myths and Forgotten Facts by D. J. Norman-Cox, supplemented and checked by the other books in the bibliography. As Norman-Cox notes in the preface to his book, "Juneteenth 101 is a survey of Juneteenth's most egregious myths. Castigating wrong-sayers is not its purpose" (9). The same is true of the purpose of this article which is intended to draw attention to the same problem Norman-Cox clarifies:

Scholarly research of Texas emancipation events collectively called "Juneteenth" is plentiful, but celebrants who are not history scholars (a.k.a. the majority of Juneteenth revelers) remain steeped in emancipation myths. Unfortunately, thanks primarily to the internet, each year the volume of inaccurate information grows exponentially, increasing the validity of bogus folklore while obscuring reality. (9)

Separating what actually happened on 19 June 1865 and afterwards from the myths surrounding the event not only clarifies the history of Juneteenth but also encourages one to ask how the myths were created and what purpose they came to serve; a question left open to each individual reader to pursue.

Myth 1: General Order No. 3 Ended Slavery in the United States

General Order No. 3 did not end slavery in the United States when it was issued on 19 June 1865. Slavery was abolished by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution on 6 December 1865. General Order No. 3 explicitly references the people of Texas, not the United States, and only served to announce enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. It reads:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere. By order of G. Granger, Major General Commanding/F.W. Emory. Major & A.A. Gen'l. (Cotham, 199)

Not only did General Order No. 3 not end slavery in the United States, it did not even effectively end slavery in Texas on 19 June 1865 because, lacking a modern-day system of mass communication, it took time to get the news out via handbills, telegraph, and newspapers. Distribution of the order began on 20 June 1865; only the people of Galveston received the order on the 19th.

Myth 2: It took over two years for the slaves in Texas to learn they were free/Texans did not know war was over until 19 June 1865

Like Myth 1, this myth is often repeated in claiming that slaves held in Texas had no knowledge of the Emancipation Proclamation until 19 June 1865 and, further, that Texan slave owners were equally ignorant of the proclamation, or that the Civil War had ended, and they were legally obligated to free their slaves. The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation was issued on 22 September 1862 and was published in full in the Houston, Texas newspaper The Tri-Weekly Telegraph on 17 October 1862. The proclamation was regularly referenced in Texas newspapers from that date through December 1864. Most slaves were illiterate as it was against the law to teach a slave to read, but they certainly could and did hear their masters discussing the proclamation. There was nothing they could do to claim their freedom, however, as Texas was part of the Confederacy and felt no obligation to comply with an executive proclamation from a government they were at war with. Slaves and masters in Texas were, therefore, fully aware of the proclamation from as early as 1862, and Texans knew the Civil War was over by late May or early June 1865.

Myth 3: A messenger carrying news of the Emancipation Proclamation was killed en route to Texas

This myth has been repeated in videos and commentaries to explain Myth 2. Allegedly, a lone Union courier was on his way to Texas with the news of the Emancipation Proclamation, in either 1862 or 1863, when he was overtaken and murdered by Confederate sympathizers, and this is why Texan slaves and masters had no knowledge of the proclamation until 19 June 1865. This myth makes no sense on any level. There would have been no reason for a Union soldier to be sent into enemy territory to deliver a proclamation for any reason, much less a proclamation that had already been communicated via telegraph and published in newspapers beginning in 1862.

Myth 4: Texas was the last slave-holding state

Texas was not the last state to retain slavery; it was the last slave-holding state of the Confederacy to free its slaves, but the border states of Delaware and Kentucky continued the institution until it was abolished nationwide by the 13th Amendment in December 1865. There were also certain parishes of Louisiana that followed that same policy. Even after the ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, many former slaves continued to work and live in conditions only slightly improved from what they had known before and these included slaves in the border states, not only those which been part of the Confederacy.

Myth 5: President Lincoln issued General Order No. 3

President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated on 15 April 1865, two months before General Order No. 3 was issued in Galveston, Texas. He had nothing to do with the order in any capacity. General Order No. 3 was issued by Major General Francis J. Herron in Louisiana on 3 June 1865, copied by General Philip Sheridan, and given to General Gordon Granger who assigned its issuance to his subordinate Major F.W. Emory (also given as Emery) who saw to its posting, distribution, and enforcement. This myth seems to have developed by conflating Lincoln and his Emancipation Proclamation with General Order No. 3 which enforced that directive.

Myth 6: General Order No. 3 was read from Ashton Villa

A popular myth is that General Order No. 3 was read by Granger from the balcony (or the porch or front yard) of Ashton Villa, the home of Confederate Colonel James Moreau Brown, and formerly the Galveston headquarters of the Confederacy. There is no evidence that General Order No. 3 was publicly read by Union officers to an audience at all but, as Norman-Cox points out, it is highly unlikely it would have been read from the balcony of the home of a leading Confederate officer. The Osterman Building was the headquarters of the Union Army District of Texas in Galveston, and General Order No. 3 was issued from this location (signified by a Texas State historical marker at the site today), but there is no record of it being read publicly from there. Major Emory was tasked with making sure the order was distributed which was dealt with through handbills, newspapers, and telegraph. Masters were expected to read the order to their slaves and announce their freedom – though not all masters complied until they were finally forced to.

Myth 7: There were celebrations throughout Texas on 19 June 1865

General Order No. 3 was only announced in Galveston, Texas on 19 June 1865, and, fearing public unrest, General Granger prohibited public gatherings that same day. Whatever celebrations took place, they would have had to have been small events, short-lived, and would only have taken place in Galveston. News of General Order No. 3 was not sent from Galveston until 20 June, and many newspapers throughout Texas did not publish the order until a week later so none of the former slaves allegedly celebrating state-wide would have even known they had something to celebrate.

Myth 8: Juneteenth is the oldest celebration of emancipation in the United States

This myth claims that Juneteenth is the oldest continuous celebration of emancipation in the United States, and this claim is false for two reasons. First, because Watch Night – a vigil held by abolitionists and sporadic enclaves of slaves on 31 December 1862 in anticipation of the Emancipation Proclamation's issuance on 1 January 1863 – predates it. Watch Night continues in the present as part of New Year's Eve celebrations in African American churches. Second, owing to racist policies and the social pressure of Jim Crow laws, Juneteenth was not celebrated – or seems to have been poorly observed – in the early part of the 20th century. Juneteenth seems to have only been continuously celebrated since 1938 when Texas officially declared 20 June as Emancipation Day.

Myth 9: Everyone was always welcome at Juneteenth celebrations

The holiday now known as Juneteenth was originally called "Freedom Day" and, although women and children participated in the early celebrations, they were eventually excluded as the event became focused primarily on voting rights. Since slaves had never had the opportunity to vote, Freedom Day served as instruction seminars on politics and voting. Since women were not allowed to vote until 1920, their participation was discouraged. Women and children only became regular participants in Juneteenth celebrations after 1920, although there is evidence for both attending events in small numbers before that date.

Myth 10: Juneteenth was first celebrated on 19 June 1866

19 June is now recognized as Juneteenth and celebratory speeches sometimes claim the event has been recognized on that date since the first anniversary of the issuance of General Order No. 3 – on 19 June 1866. Actually, the first Freedom Day was celebrated on 1 January 1866 to commemorate the three-year anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation. Another Freedom Day was then celebrated on 19 June 1866, but it was not the first.

Conclusion

There are many more myths surrounding Juneteenth than just these ten, and readers are encouraged to consult Norman-Cox's excellent work on the subject for an in-depth and engaging treatment of them. Many of the above, and others, may seem like harmless trivia but, in fact, distort the history of the event Juneteenth commemorates, even if they were not intended to. Norman-Cox writes:

No evidence has been found to suggest Juneteenth's popular myths were intentionally generated. Many inaccuracies…appear to be rooted in poorly worded explanations, and failure by Juneteenth champions to fact check. (9)

Still, Juneteenth is too important a holiday to allow for such misunderstandings, even if some seem trivial, as the event celebrates personal and collective freedom and commemorates an official proclamation of "an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property" between people who had been enslaved and those who had kept them in bondage. Although the myths that have grown up around the event do not detract from its significance, the truth of Juneteenth is far more interesting and needs no embellishment.