The Battle of the Nile (1-2 August 1798), or the Battle of Aboukir Bay, saw a British fleet led by Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) destroy a French fleet at Aboukir Bay near the Rosetta mouth of the Nile River. It was one of the most decisive naval battles of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

The battle was the result of a three-month-long campaign in the Mediterranean Sea, as Nelson hunted a massive French fleet that was ferrying General Napoleon Bonaparte and a 38,000-man army to Egypt. After disembarking Bonaparte's army, French Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers moved his fleet to Aboukir Bay, about 19 kilometers (12 mi) east of Alexandria, where he was attacked by Nelson on 1 August 1798. Nelson split his warships into two squadrons and enveloped the French battle line, with one squadron passing between the French ships and the shore, and the other attacking the seaward side. At the climax of the battle, the French flagship L'Orient exploded, and the British managed to destroy or capture most of the French ships by the morning of 2 August.

The British victory had profound consequences for the continuation of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). Prior to the battle, Great Britain had been fighting Revolutionary France alone, but Nelson's victory helped convince other European powers to join against France in the War of the Second Coalition (1798-1802). By destroying the French fleet, Nelson also cut Bonaparte and his army off from Europe, contributing to the eventual failure of Napoleon's Campaign in Egypt and Syria. Although the Battle of the Nile remains less famous than the later Battle of Trafalgar, it arguably played an even larger role in the annihilation of French naval power, which allowed for Britain's century-long domination of the seas; for this reason, it has been called "the most decisive naval engagement of the great age of sail" (Maffeo, 272).

The French Armada

By early 1798, the French Revolutionary Wars appeared to be winding down. After five bloody years, the armies of the French Republic had defeated almost all of their enemies and had conquered the Low Countries, the Rhineland, and northern Italy, but before France could claim total victory it still had to defeat its longstanding rival Great Britain, which stubbornly refused to make peace. Initially, the French contemplated a direct invasion of the British Isles before an alternative plan was suggested by the popular young General Napoleon Bonaparte: an invasion of Egypt. By establishing a French colony in Egypt, Bonaparte hoped to create a base from which he could launch an attack on British India and bring the war to an end. His plan was approved, and Bonaparte spent March and April assembling an army of 38,000 men.

A massive armada of French ships gathered in Toulon and several other ports along the Mediterranean that consisted of 13 ships-of-the-line, 13 frigates, 23 corvettes and sloops, and hundreds of transport vessels of varying sizes. The fleet's flagship was the colossal 124-gun, three-decked warship called L'Orient, which was possibly the most powerful warship in the world at the time. Since the depleted French navy lacked sufficient manpower, local fishermen, privateers, and even prisoners were pressed into service as sailors, but even this was not enough to bring the crews up to full strength. Overall command was given to Vice-Admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers, a 45-year-old naval officer from a minor aristocratic background. Only Brueys and a handful of his officers were told of the expedition's purpose; to maintain the element of surprise, Bonaparte went to great lengths to conceal the fleet's destination even from his own men.

Bonaparte's discretion paid off since English spies quickly learned about the existence of the fleet itself but were unable to discover why it was gathering. When word reached London, the cabinet of Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger was left guessing at its destination; the war secretary Henry Dundas suggested Egypt as the destination but was dismissed by his colleagues who told him to think "with a map in your hand, and with a calculation of distances" (Rodger, 458). Eventually, orders were sent to Vice-Admiral St. Vincent, commander of the Mediterranean fleet, to find out what the French were up to. St. Vincent, in turn, dispatched a squadron of three warships commanded by his protégé, Rear-Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson.

At 39 years old, Nelson was the youngest rear-admiral in the Royal Navy but had already built quite a distinguished reputation and had the battle scars to prove it; in 1794, he had lost the use of his right eye during the siege of Calvi, and he had been wounded by grapeshot three years later at the Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, which had led to the amputation of his right arm. Having only just recovered from the loss of his arm, Nelson set out aboard his flagship Vanguard on 2 May, under orders to merely observe the French fleet at Toulon and report back. But on 12 May, as Nelson's squadron remained stationed off Toulon, a vicious storm scattered the ships and dismasted Vanguard. Nelson made the decision to head to Sardinia for repairs, but by the time he returned to his station on 27 May, the French had already set sail. On 7 June, St. Vincent supplied Nelson with 10 additional ships-of-the-line as reinforcements along with a new set of orders: Nelson was no longer to simply watch the French fleet but to "use your utmost endeavors to take, sink, burn or destroy it" (Strathern, 55). Nelson dutifully set off southwards along the Italian coast; the hunt had begun.

Cat & Mouse

After being delayed by the same storm that had scattered Nelson's squadron, the French fleet departed Toulon on 19 May; each ship lowered its colors in salute as it passed by L'Orient. The fleet first arrived off the coast of Malta on 10 June. When the Knights of St. John refused to allow the fleet entry into the harbor, Bonaparte ordered an invasion, and Malta fell after minimal resistance. The French spent several days on the island, during which Bonaparte raided the Maltese treasury; 7 million francs' worth of gold, silver, and jewels were stowed in the hold of L'Orient. Finally, on 19 June, the French set sail for Alexandria, taking the long route around Crete to throw off their British pursuers. Taking extra precautions, Vice-Admiral Brueys ordered every merchant ship they came across to be seized and detained until they had reached Egypt.

Nelson, meanwhile, came across a Genoese merchant ship that told him that the French had left Malta on 15 June and were sailing east. This confirmed Nelson's suspicions that the French were sailing for Alexandria and, assuming the French had a six-day head-start, he immediately raced toward Egypt. Yet the merchants had been misinformed and reported that the French had left Malta four days earlier than they actually had. In reality, the French were much closer; on the night of 22-23 June, the British and French fleets passed within miles of one another. Concealed by a thick fog, the French sailors listened in anxious silence as the booms of the British signal cannons resounded at regular intervals. Nelson arrived at Alexandria on 28 June, but he saw no sign of the French fleet. Realizing he had lost the trail of the enemy, Nelson came to the verge of a nervous breakdown; he waited 24 hours before sailing out of Alexandria.

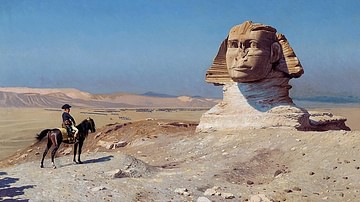

The French arrived off Alexandria on 1 July. The poet Nicolas Turc described the awe-inspiring sight: "When the inhabitants of Alexandria looked to the horizon, they could no longer see the sea, only the sky and ships. They were seized by a terror beyond the imagination" (Strathern, 66). On 2 July, the French captured the city and spent the next few days disembarking. Since Alexandria's harbor was too shallow for the French warships, Bonaparte ordered Brueys to anchor at Aboukir Bay, with the addendum that Brueys move to Corfu if the bay proved too dangerous. Wanting to stay close by in case the army needed to be evacuated, Brueys opted to remain in Aboukir Bay; he anchored his ships-of-the-line there as Bonaparte led his army into the Egyptian desert.

Aboukir Bay

30 km (18 mi) wide, Aboukir Bay seemed to provide an ideal defense for Brueys' fleet; the bay was protected by a peninsula with a fort on its tip, and by rocky shoals along the coast. Brueys decided to position his ships in a battle line, with the starboard side facing the open sea and the port side facing the shoreline, to disembark supplies more easily. Each ship was connected to the stern and bow of its neighbor with cables, thereby creating a formidable barrier across the bay. The most powerful warships were placed in the center and rear of the line, since the position of the shoals would hypothetically force the British to attack there. Brueys placed his weaker ships in his vanguard, believing that those vessels could swoop around and counterattack while the enemy was engaged with the larger ships. However, Brueys had made one fatal miscalculation; he had left too much open water between the port side of his fleet and the shoals, theoretically giving an enemy ship enough room to slip through.

As the French settled into Aboukir Bay, Nelson and his officers were sailing west of Crete, desperately searching for the enemy. After a brief pitstop on Sicily to take on supplies, Nelson turned east again, putting into port at Coroni off the Peloponnese on 28 July. Here, Nelson finally had some luck; the local Ottoman governor had been informed of the French invasion of Egypt. This was corroborated when one of Nelson's ships captured a French brig that was on its way to Egypt laden with wine. Nelson immediately sailed for Egypt, arriving off Alexandria on the morning of 1 August.

Although the French tricolor was visible flying over the city, the ships themselves were nowhere to be found and Nelson sent the ships Zealous and Goliath to search the coasts for the elusive fleet. At around 2:30 in the afternoon, the lookouts on Zealous caught sight of the forest of French sails anchored in Aboukir Bay. Zealous signaled that the enemy had been found, and by 4 p.m., the majority of the British ships had rounded the peninsula to enter the bay. Aboard Vanguard, Nelson took an early dinner with his captains, who would soon become famous as "Nelson's Band of Brothers"; raising a toast, Nelson told them that tomorrow he would be bound for either the House of Lords or Westminster Abbey, where Britain's military heroes were buried.

By this time, the British ships were spotted by the French, who were caught in an awkward position; most of the crew were ashore, digging wells for fresh water. Though Brueys ordered his men back to the ships, there was no sense of urgency; with only a few hours of sunlight left, it was unlikely Nelson would attack so close to dark. Yet Nelson had a favorable northwest wind that he was unwilling to risk losing, so he signaled for his ships to attack.

Nelson Attacks

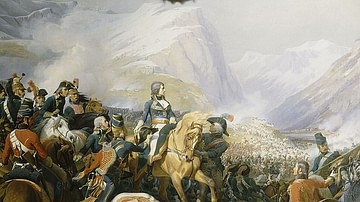

At the head of the British line was Goliath, whose commander, Captain Thomas Foley, noticed the gap between the French fleet and the shore. Though he ran the risk of running aground on the shoals, Foley took the initiative and sailed Goliath into the channel. This allowed him to attack the weak French vanguard, which Brueys had believed to be safe; Goliath opened fire on the bow of the first French ship, Guerrier, inflicting severe damage. Royal marines fired at Guerrier's decks as Goliath cruised past it, anchoring beside the next French ship, Conquérant, which also received a crucial hit from Goliath's guns. Noticing the success of Captain Foley, the captains of Zealous, Orion, and Audacious followed Goliath into the channel, while Nelson led the rest of the ships down the seaward side; before long, the French ships were being bombarded from both sides.

The swiftness of the British attack had taken the French completely by surprise; many sailors were still ashore, while most of the French captains were still aboard L'Orient, where they had been conferring with Brueys. The captains rowed back to their ships amongst the carnage, shouting orders. Darkness rapidly gathered, and the full moon was blotted out by the smoke from the guns, leaving the lanterns on the decks and the flashes of cannon fire as the only sources of light. By 8 p.m., the badly battered Conquérant had surrendered, followed closely by Guerrier, which had been completely dismasted. The British ships continued down the French line, firing broadsides at the French ships Spartiate and Aquilon. During one of these broadsides, at approximately 8:30, Nelson was struck in the forehead by shrapnel, causing a flap of skin to fall over his good eye. Believing the wound was mortal, Nelson exclaimed, "I am killed," as he was brought below decks (Strathern, 163). Once the wound had been dressed, however, Nelson was back on deck, resuming his command.

The chaos worsened as the night became darker, with cannonballs, musket shots, and debris flying every which way. One of the British ships on the seaward side, Bellerophon, accidentally drifted to the French center where it came face to face with the towering L'Orient. With only two gundecks and 30 cannons, Bellerophon hardly stood a chance. At around 8:30 p.m., Bellerophon had sustained 200 casualties and was completely dismasted; its commander cut the anchor cables and the ship drifted off into the night. L'Orient received only a moment's respite before a larger British ship, Swiftsure, anchored beside it and began unleashing fresh broadsides. Before long, part of L'Orient was on fire, and both of Brueys' legs were blown off by a cannonball. Rather than go below decks, Brueys had himself strapped to an armchair on deck so he could continue giving orders. Another cannonball struck him in the stomach, nearly cutting him in two; within 15 minutes he was dead. L'Orient's captain Luc-Julien Casabianca was also wounded by flying debris and was taken below, leaving his 12-year-old son, Giaconte, waiting on deck.

Meanwhile, two more ships in the French vanguard had surrendered, allowing more British warships to focus on the enemy center. The British ship Majestic exchanged fire with the 80-gun Tonnant and suffered some of the heaviest British casualties during the battle, with its captain, George Westcott, amongst the dead. As Majestic pulled away, Swiftsure, which had begun to drift away from L'Orient, began firing on Tonnant as another British ship, Alexander, continued to fire on the French flagship.

Destruction of L'Orient

Before long, the fire had spread on L'Orient and it became clear that the ship was close to exploding. Anticipating the inevitable, several French officers and sailors jumped into the water; young Giaconte Casabianca was urged to do the same, but he refused to abandon his father's side. At around 10 p.m., the mighty French flagship exploded with a tumultuous roar; every nearby ship was shaken by the blast which was heard by Bonaparte's soldiers in Rosetta, 32 km (20 mi) to the east. Body parts, flaming debris, and bits of Maltese treasure were hurled into the air to come raining back down. There was a lengthy lull in the battle following the explosion as sailors rushed below decks to shelter from the falling debris or hurried to put out flames on their own ships. Although there were some survivors, most of L'Orient's 1,000-man crew perished in the explosion.

By midnight, only Tonnant remained engaged with the British ships; its commander, Commodore Petit-Thouars, refused to surrender even though his ship had been dismasted and he had lost both legs and an arm. Propped up on deck in a bucket of wheat, Petit-Thouars ordered the colors to be nailed to the mast to prevent it from being struck. But before long, Petit-Thouars died of his wounds and Tonnant, too, surrendered. When the sun finally rose at 6 a.m. on 2 August, the outcome of the battle was no longer in question. French Rear-Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, who commanded the 80-gun Guillaume Tell in the rear, ordered a retreat. Only two French ships-of-the-line and two frigates escaped Aboukir Bay, the rest of the French ships having been captured or destroyed by the British. Although two British ships had been severely damaged – Bellerophon and Majestic – none had been destroyed. While French losses ranged between 2,000-5,000 men, the British lost only 218 killed and 677 wounded. When Nelson finally looked out at the floating carnage of the battle, he remarked, "Victory is not a name strong enough for such a scene" (Blanning, 195).

Aftermath

The Battle of the Nile marked a turning point in the French Revolutionary Wars. Not only did it cripple France's ability to wage war at sea and strand Bonaparte's expeditionary army in Egypt but it also convinced the enemies of Revolutionary France to join together in a second anti-French coalition. When word of the victory reached London on 2 October, it was greeted with grand celebrations and Nelson became something of a celebrity; he was elevated to the House of Lords, as he had hoped, becoming Lord Nelson of the Nile. The battle remains one of the most celebrated in the history of the British Navy and is often regarded as one of the most important battles of its age.