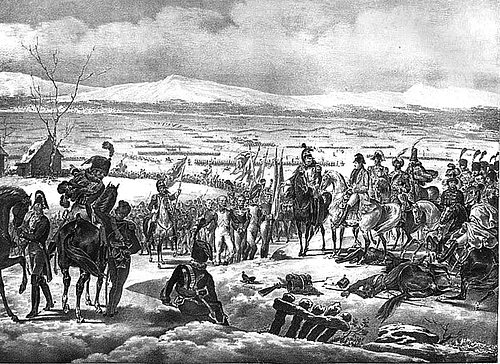

The Battle of Eylau (7-8 February 1807) was a bloody but inconclusive military engagement during the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). Fought on the snowy fields of Poland, the two-day battle resulted in a draw. Eylau marked the first serious setback for Napoleon's Grande Armée, inflicted by a Russian army under Levin August von Bennigsen.

Background

On 14 October 1806, Napoleon's Grande Armée soundly defeated the Prussian army at the Battle of Jena-Auerstadt. Within two weeks, French soldiers were marching through the streets of Berlin, forcing King Frederick William III of Prussia (r. 1797-1840) to flee with his court to the safety of Königsberg in East Prussia (modern Kaliningrad, Russia). Frederick William refused to admit defeat, hoping that all might be saved by his ally, Russia. The closest Russian armies were in Prussian-occupied Poland and were led by the 68-year-old Field Marshal Count Mikhail Kamensky. However, Kamensky was a skittish commander who decided to pull his army away from Warsaw. As a result, the French advance into Poland was opposed only by the muddy roads and inhospitable weather conditions.

As the Prussian king watched helplessly from Königsberg, the French emperor entered the Polish city of Posen (Poznań), where he was greeted with rapturous fanfare. In the late 18th century, the three partitions of Poland (in 1772, 1793, and 1795) had erased Poland from the map of Europe, its lands carved up and divided between Prussia, Russia, and Austria. The Poles dreamed of nationhood and saw Napoleon as the man to restore it to them. Though Napoleon was eager to play the part of liberator, he recognized the fragility of the situation; a revived Poland would offend neutral Austria and make it harder for Napoleon to negotiate with the Russian tsar. Consequently, Napoleon made sure not to make any explicit promises, though he did form six Polish departments into a semi-autonomous political entity, overseen by a council of seven Polish noblemen.

The Polish Campaign

Kamensky's Russian army, meanwhile, had withdrawn to Pułtusk, some 65 kilometers (40 mi) north of Warsaw. After entering Warsaw unopposed on 19 December, Napoleon ordered all his army corps across the Vistula River, hoping to advance as far as possible before the full onset of winter. This was unwelcome news to the soldiers of the Grande Armée, who, in the words of French General Jean Rapp, showed "a lively distaste to crossing the Vistula" (Chandler, 517). After two months on the march, the French soldiers were tired, demoralized, and homesick; many had not seen France since the summer of 1805. Morale was worsened by the miserable weather, the flooded roads, and a scarcity of food, the latter of which caused soldiers to joke that it was necessary to know only five Polish words: “Chleba? Nie ma. Woda? Zaraz!” ("Bread? There is none. Water? Immediately!") (Roberts, 432).

Despite their misery, the French soldiers were ready to fight. On 22 December, the French III Corps under Mashal Louis-Nicolas Davout discovered a detachment of 15,000 Russian troops under General Alexander Ostermann-Tolstoy, who were guarding the crossing of the Wkra River near the town of Czarnowo. Napoleon reconnoitered the area personally before ordering Davout to press forward in a surprise night attack, and the crossing was captured at the price of 1,400 casualties for each side. Sporadic skirmishes lasted throughout the next day as the French army got into position, but when Napoleon learned that Kamensky was preparing to retreat, he ordered an attack.

On 26 December, French Marshal Jean Lannes' V Corps of 25,000 men attacked a superior Russian force of 35,000 men at the Battle of Pułtusk; amidst a driving snowstorm, Lannes' men managed to capture the village of Pułtusk only to be forced out again by a Russian counterattack. The same day, two French corps under marshals Davout and Charles-Pierre Augereau engaged 18,000 Russians under Prince Galitzin (also given as Golitsyn) at the Battle of Gołymin. Outnumbered, Galitzin was able to hold out until dark, at which point he was able to extricate his troops from the battlefield.

Winter Quarters

The Russian army was able to make good its escape and go into winter quarters. Kamensky, having incurred both the frustration of his subordinates and the wrath of the tsar with his inaction, resigned and was replaced as commander-in-chief by one of his corps commanders, Levin August von Bennigsen. Born in Hannover, Bennigsen was one of the many German officers serving the Russian Empire and was a capable officer. However, the change of command led to intrigue in the Russian army; Bennigsen's subordinate and fellow German, Friedrich von Buxhoevden, was enraged that he had not been chosen as commander-in-chief and even challenged Bennigsen to a duel.

The French also went into winter quarters along the banks of the Vistula, and Napoleon returned to Warsaw. There he met a young and beautiful Polish noblewoman, Countess Marie Walewska, with whom he began one of his most enduring romantic affairs. But while Napoleon enjoyed the warmth of Countess Walewska's bed, his men were suffering in the cold Polish fields. Dwindling supply trains had reached the point where some men were reduced to drinking horse blood out of saucepans, while the despair led to around 100 suicides in the French army by Christmas. The growing rivalries between Napoleon's marshals led them to divert one another's supply trains. By the New Year, the French VI Corps under Marshal Michel Ney was running dangerously low on provisions. Although he was under strict orders to stay put until spring, Ney decided to strike north on 10 January 1807, hoping to capture the supply depot at Königsberg.

But Ney would find more than just provisions when he arrived at Heilsberg (Lidzbark Warmiński) a week later. Here, he stumbled right into General Anton Wilhelm von L'Estocq's Prussian Corps of Bennigsen's army, which had been moving west. After interrogating captured stragglers, Ney discovered that Bennigsen was launching a surprise attack, marching his 63,000 Russians and 13,000 Prussians through the Forest of Johannisberg to conceal his movements from French scouts. Ney immediately informed Napoleon, who ordered his army out of winter quarters on 27 January.

The Failed Trap

While most commanders would have been alarmed to learn that an enemy army was embarking on a surprise attack, the wily French emperor saw a golden opportunity to set a trap of his own. If Bennigsen continued marching in a westward direction, he would inevitably expose his left flank and rear to a French attack. Napoleon ordered Marshal Jean Bernadotte's I Corps to lure the Russians further west while the rest of the army got into position. Bernadotte obeyed, although the rest of the army was slowed down by thick snow. Napoleon wrote fresh orders for Bernadotte to rejoin the French left by a secret nighttime march. However, these plans were fatefully entrusted to a young officer who had only recently arrived at the front. Unfamiliar with Poland, the officer became lost and was captured by a group of Cossacks before he had time to destroy his dispatches, which contained the dispositions of the entire French army.

Bennigsen was now aware of Napoleon's trap while Marshal Bernadotte was left in the dark. On 1 February, the Russians made a sharp turn to the east, to the safety of the Alle River (Łyna); unaware that his scheme had been uncovered, Napoleon hurriedly pursued. By 6 February, Bennigsen had crossed the Alle, leaving his rearguard under General Michael Barclay de Tolly to fend off French Marshal Joachim Murat's Cavalry Reserve at Hoff; Barclay de Tolly succeeded in holding back the French at a cost of 2,000 Russian casualties. However, Bennigsen knew he could not keep running forever. If he wanted to defend Königsberg, he had to stand his ground. He moved his army to the small East Prussian town of Preussisch-Eylau, around 35 kilometers (20 mi) south of Königsberg. He had about 67,000 men at hand and was counting on the arrival of L'Estocq's 9,000 Prussians.

Napoleon, meanwhile, had 45,000 troops readily available, namely Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult's IV Corps, Marshal Augereau's VII Corps, Murat's Cavalry Reserve, and his Imperial Guard. Though he was outnumbered, there was the possibility of reinforcements; Ney's Corps of 14,500 men was busy pursuing L'Estocq, while Davout's Corps of 15,000 was only a few hours away.

First Day: 7 February

Situated on the road to Königsberg, Eylau (modern Bagrationovsk, Russia) was a small town of only 1,400 inhabitants. It rested about 2.5 kilometers (1.5 miles) from a plateau and was situated near two lakes: Lake Tenknitten to the left and Lake Waschkeiten to the right. A small hillock stood to the right of the town, upon which sat a church and a cemetery. Modern scholarship is divided on whether Napoleon truly meant to fight a battle at Eylau. According to Baron Marbot, an officer on Augereau's staff, French soldiers had gone into the town to secure shelter, but they were spotted by a Russian patrol who fired on them, and the French returned fire. The sound of musket fire drew additional soldiers from both armies until the small skirmish at Eylau had blossomed into a bloody struggle.

At 2 p.m., following the sound of the skirmishing, Murat's cavalry and the head of Marshal Soult's infantry approached the plateau in front of Eylau, defended by the Russian vanguard under Prince Peter Bagration. Soult ordered two battalions forward to drive the Russians off the ridge; after being battered by Russian artillery, these battalions were attacked by the Russians with fixed bayonets. The St. Petersburg dragoons, charging over the frozen Lake Tenknitten, caught the French battalions by surprise and captured an imperial eagle standard. A counterattack by French dragoons prevented the Russians from following up on this success, while a barrage from Soult's artillery forced Bagration to pull back toward the main body of the Russian army.

Meanwhile, in the town, the bloodiest fighting was developing around the hillock with the church and cemetery. It was initially stormed by the division of French General Saint-Hilaire; in this early stage of the fighting, Russian General Barclay de Tolly was severely wounded in the arm from grapeshot. Though Prince Bagration would have liked to abandon Eylau, Bennigsen ordered it recaptured at all costs. Three columns of Bagration's infantry were sent into the town, running straight into canister shot from French artillery. Despite suffering heavy losses, by 6 p.m., the Russians had retaken most of the town, though the church and cemetery remained in French hands. Bennigsen must have decided it was no longer worth it; he ordered his men to withdraw to the heights east of Eylau at 6:30. The battle for the Eylau cemetery had cost each side around 4,000 casualties.

Although the French controlled the town, they would find no comfort this night. Some officers and men were fortunate enough to shelter in the houses, but for most of the French soldiers (and for all the Russians), the night was spent exposed to the elements, which included a snowstorm that began after midnight and would continue throughout the next day. The streets of Eylau were clogged with corpses, and the French wagon convoys were unable to make it up the roads, leading many men to go without supper. But any suffering the men experienced that night was quickly eclipsed by the horrors of the next day.

Second Day: 8 February

Around 8 a.m., the 460 Russian guns began a hellish bombardment on the town. The French cannons returned fire, commencing an artillery duel that lasted for two hours. Napoleon spent that time concocting a battle plan: Soult's Corps, supported by every available gun, was to pin the Russians down and absorb the brunt of their attack until Davout's Corps could arrive, emerging on the enemy's left flank. The hope was that Davout could turn the Russian left flank, at which point Augereau and Murat would be sent against the Russian right; Ney's arrival from the north would complete the encirclement, trapping the Russian army between French corps on all sides. Historian David G. Chandler remarks that, if this double envelopment had succeeded, it may have rivaled Hannibal's achievement at the Battle of Cannae (539).

At 9:30, Soult's Corps was ordered to threaten the Russian right flank to distract Bennigsen's attention away from Davout, who would be approaching any moment on the left. Soult's men advanced 550 meters (600 yards) before the impatient Russians charged out to meet them; within half an hour, Soult was forced back into Eylau. On the opposite end of the battlefield, the first division of Davout's Corps appeared only to be charged by Ostermann-Tolstoy's Russian cavalry. Napoleon was unnerved by these developments; he had not expected Soult to be pushed back so soon, nor had he envisaged that Davout would be noticed so quickly. To salvage the situation, the emperor decided to send Marshal Augereau's Corps of 9,000 men against the Russian left, to help ease the pressure on Davout. Saint-Hilaire's division would also join the attack.

Augereau dutifully got his Corps into position for the charge. But the marshal was very ill; he had to be propped up on his horse by an aide-de-camp and wore a scarf wound around his head beneath his hat. Augereau's illness may have been one reason for the disaster that happened next; another reason was the driving snowstorm, which severely obscured visibility. In any case, shortly after Augereau's Corps began its march, it veered off course; rather than heading for the battle on the Russian left flank, the French instead marched directly toward a massive 70-gun Russian battery. Augereau's men were soon blasted by grapeshot at point-blank range. Within 15 minutes, 5,000 of them were killed or wounded, with Augereau himself struck in the arm. The survivors were sent running back to the Eylau cemetery. Saint-Hilaire's division, which had stayed on course, was now alone on the Russian left and soon found itself surrounded by Russian cavalry.

The dire situation was worsened when a Russian column of 5,000 men charged into Eylau, commencing bitter hand-to-hand fighting in the streets. At one point, the Russians made it to the bell tower that Napoleon had been using as his headquarters. Napoleon likely would have been killed or captured, had it not been for his brave personal escort, who held off the Russians long enough for the Imperial Guard to arrive. It was at this point that the blizzard finally abated, and Napoleon saw an opportunity to salvage the day. At 11:30, he summoned his dashing cavalry commander, Marshal Murat. Pointing to the advancing Russians, Napoleon asked, "Are you going to let those fellows eat us up? Take all your available cavalry and crush that column." (Roberts, 443).

Murat's Charge

What followed is widely regarded as one of history's greatest cavalry charges. Murat gathered every available cavalry trooper, which amounted to some 11,000 men, and led them across the 2.3 kilometers (2,500 yards) of open ground toward the Russian lines. The cavalry quickly mopped up the Russian troops who had made it to Eylau, before dividing into two wings. The first wing came to the rescue of Saint-Hilaire's isolated division, while the second cut down the Russian gunners who had repulsed Augereau's charge. The two wings combined once more to crash through the Russian center, only to re-form behind the Russian line and charge back the way they had come, galloping back to the safety of the French lines. For the price of 1,500 cavalrymen lost, Murat had sewn chaos in the Russian army and had bought Napoleon time to re-form his own lines.

Murat's charge had also cost Bennigsen his best chance of victory that day. Davout was now fully in position, and at 1 p.m., he charged forward in a broad encirclement of Ostermann-Tolstoy's vulnerable flank. Davout pushed the Russians back for two hours, but just when it appeared the Russian line was about to break, L'Estocq emerged onto the field with 9,000 Prussians. Rallying the fleeing Russian soldiers, L'Estocq's charge gained momentum until it slammed into Davout's Corps, forcing Davout to give up hard-won ground. At last, at around 7 p.m., Marshal Ney arrived on the field with 14,500 fresh troops. By this point, the fighting was winding down, and by 10 p.m., the Battle of Eylau was over.

Aftermath

At 11 p.m., Bennigsen held a war council. Though his staff urged him to stay and fight for a third day, Bennigsen was shaken by the sudden arrival of Ney's Corps and decided to withdraw. The Russians began an orderly retreat that night; the French let them go, too exhausted to pursue. Since Napoleon was left in possession of the field, he claimed victory, though the battle was, at best, a stalemate. The Russians had lost between 15-26,000 casualties against 15-29,000 losses for the French. Eylau was perhaps the bloodiest battle of the Napoleonic Wars thus far, as noted by Ney, who remarked upon observing the carnage: "What a massacre! And without any result!" (Roberts, 445).

Indeed, the only results were the further demoralization of the French troops and Europe's realization that the Grande Armée was not, in fact, invincible. After Eylau, the Russian and French armies once again withdrew into winter quarters. The decisive engagement of the war would be fought four months later at the Battle of Friedland (14 June 1807).