The Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi (c. 1700 BCE) is a Sumerian and later Babylonian poem on the theme of unjust suffering, which is thought to have influenced the biblical Book of Job. Also known as The Poem of the Righteous Sufferer, the title translates as "I will praise the Lord of Wisdom" and is among the best-known works of ancient Mesopotamian literature.

The original work, dated to c. 1700, is a Sumerian composition, while the better-known Babylonian version dates to the reign of the Kassite king Nazi-Maruttash (c. 1307-1282 BCE), who ruled from Babylon. In the original, the speaker is Tabu-utul-Bel, an official of the city of Nippur, while in the Babylonian version, he is Shubshi-meshre-Shakkan, also a wealthy official, and both works address the problem of undeserved suffering by a pious man who maintains faith in his god even when it seems that god cares nothing for him. This theme, naturally, has drawn comparisons between this poem, the Sumerian work Dialogue Between a Man and his God (c. 2000-1600 BCE), and the Hebrew composition, the Book of Job, dated to the 7th, 6th, or 4th centuries BCE.

The title Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi technically applies only to the Babylonian work (as it is the first line of the piece), but is sometimes applied to the earlier Sumerian piece, which was originally designated as Poem of the Righteous Sufferer. Both works have come to be known, respectively, as The Sumerian Job and The Babylonian Job, and whether the original Sumerian version of Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi or Dialogue Between a Man and his God came first, they both predate the composition of the Book of Job, as scholar Samuel Noah Kramer notes:

The Sumerian poem in no way compares with [the Book of Job] in breadth of scope, depth of understanding, and beauty of expression. Its major significance lies in the fact that it represents man's first recorded attempt to deal with the age-old yet very modern problem of human suffering. All the tablets and fragments on which our Sumerian essay is inscribed date back to more than a thousand years before the compilation of the Book of Job. (History, 112)

The two works are often compared, however, and draw further comparison with Dialogue Between a Man and His God, as all three, while presenting their own view of seemingly unjust suffering, maintain the sovereignty of the divine, the individual's inability to grasp the meaning of that suffering, and encourage continual praise of one's god and gratitude for what that god has given as the path through personal misery to redemption.

Summary & Commentary

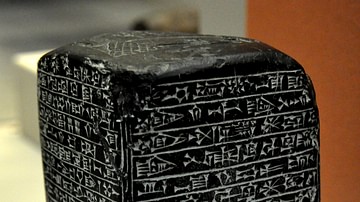

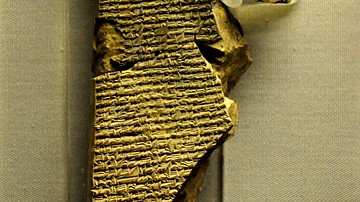

The Sumerian text was first discovered in the mid-19th century and translated by the scholar and archaeologist Sir Henry Rawlinson. Other copies of the poem were then found in the ruins of the city of Nippur (in modern-day Iraq) in the early 1950s and translated by Kramer (and others) soon after. The Sumerian work is 135 lines as compared with the more fully developed Babylonian version of four tablets containing 480 lines. The Sumerian work will be addressed in this article, but a link to the Babylonian text, translated by scholar Alan Lenzi, appears in the bibliography.

The poem begins with the speaker lamenting his suffering as he cries out for help from his god (Marduk) and receives no answer. His personal goddess is also silent, and the seers he consults offer no hope. He compares himself to one who suffers because of ingratitude toward the gods ("Like one who the sacrifice to god did not bring", line 12) but maintains he has always "thought of prayers and supplications" and how "honoring the gods was the joy of my heart" (lines 23 and 25). At the same time, he acknowledges, what one thinks is good, the gods may consider evil (lines 34-36), and no one can truly understand their plan.

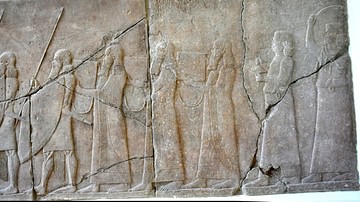

In ancient Mesopotamian religion, there were between 300-1000 deities at work at any given time, and this being so, the good that a god such as Marduk might wish for an individual could be thwarted by another such as Erra. Tabu-utul-Bel's complaint is that he should not suffer because he has done right by his god, and while no one would fault him for complaining about the many afflictions he lists, he would have had to know that it might not be Marduk's fault he was suffering, nor his own; suffering could come from any one of many deities, ghosts, or evil spirits, and for reasons no one could even guess at. The Sumerian Penitential Prayer to Every God tablet (dating from the mid-7th century BCE) makes this clear in that the penitent in that piece begs for mercy and forgiveness from whichever god he has offended unknowingly.

Even so, as the speaker is suffering, he does not dwell on his cultural theology but speaks directly to his present problem. Life is unpredictable – "He who lives at evening is dead in the morning" (line 39) – the speaker says, and one's fortunes change constantly, and seemingly so randomly, there is no way to recognize any cause and effect or meaning to any of it (lines 40-47). This, he says, is what has happened to him, and he details his suffering in lines that resonate with the same power as those of later biblical narratives including the Book of Job, Ecclesiastes, the third chapter of the Book of Lamentations, and passages from the Book of Isaiah, among others.

Like Job, however, the speaker refuses to curse his god and die. His faith and patience are rewarded when Marduk sends 'a conjurer' – a physician in ancient Mesopotamia known as an asipu, who relied on spells and 'magic' to cure illness – and the speaker's suffering is relieved. The Sumerian text breaks off at the end, but enough is preserved to recognize that the speaker, by maintaining his trust in Marduk's goodness and sovereignty, is rewarded.

The Text

The following translation of the Sumerian Ludlul-Bel-Nemeqi comes from Sir Henry Rawlinson's A Commentary on the Cuneiform Inscriptions of Babylon and Assyria, Volume IV, 60 (1850) as printed in George A. Barton's Archaeology and The Bible and reproduced on Fordham University's Ancient History Sourcebook. Ellipses indicate missing words or sentences while question marks suggest alternate translations for a word. Line numbers from the Fordham site have been adjusted to align with standard numbering. Although the original Sumerian work is 135 lines, the English translation is nine lines longer.

The reference to Ur-Bau in line 93 is most likely to a general servant of the healing goddess Bau, not to the ruler of Lagash of the same name, though this is possible as the ruler Ur-Bau associated himself closely with the divine craftsman Ninagal. The line could be suggesting that Ur-Bau appears in a dream as an emissary of Ninagal, coming to repair him. Scribes in ancient Mesopotamia frequently made topical references they felt their audience would understand.

1. I advanced in life, I attained to the allotted span

Wherever I turned there was evil, evil –

Oppression is increased, uprightness I see not.

I cried unto god, but he showed not his face.5. I prayed to my goddess, but she raised not her head.

The seer by his oracle did not discern the future

Nor did the enchanter with a libation illuminate my case

I consulted the necromancer, but he opened not my understanding.

The conjurer with his charms did not remove my ban.10. How deeds are reversed in the world!

I look behind, oppression encloses me

Like one who the sacrifice to god did not bring

And at meal-time did not invoke the goddess

Did not bow down his face, his offering was not seen;15. (Like one) in whose mouth prayers and supplications were locked

(For whom) god's day had ceased, a feast day become rare,

(One who) has thrown down his fire-pan, gone away from their images

God's fear and veneration has not taught his people

Who invoked not his god when he ate god's food;20. (Who) abandoned his goddess and brought not what is prescribed

(Who) oppresses the weak, forgets his god

Who takes in vain the mighty name of his god, he says, I am like him.

But I myself thought of prayers and supplications –

Prayer was my wisdom, sacrifice, my dignity.25. The day of honoring the gods was the joy of my heart

The day of following the goddess was my acquisition of wealth

The prayer of the king, that was my delight,

And his music, for my pleasure was its sound.

I gave directions to my land to revere the names of god,30. To honor the name of the goddess I taught my people.

Reverence for the king I greatly exalted

And respect for the palace I taught the people –

For I knew that with god these things are in favor.

What is innocent of itself, to god is evil!35. What in one's heart is contemptible, to one's god is good!

Who can understand the thoughts of the gods in heaven?

The counsel of god is full of destruction; who can understand?

Where may human beings learn the ways of God?

He who lives at evening is dead in the morning.40. Quickly he is troubled; all at once he is oppressed;

At one moment he sings and plays;

In the twinkling of an eye he howls like a funeral-mourner.

Like sunshine and clouds their thoughts change;

They are hungry and like a corpse.45. They are filled and rival their god!

In prosperity they speak of climbing to Heaven

Trouble overtakes them, and they speak of going down to Sheol.[At this point the tablet is broken. The narrative is resumed on the reverse of the tablet.]

48. Into my prison my house is turned.

Into the bonds of my flesh are my hands thrown;

Into the fetters of myself my feet have stumbled.

...55. With a whip he has beaten me; there is no protection;

With a staff he has transfixed me; the stench was terrible!

All day long the pursuer pursues me,

In the night watches he lets me breathe not a moment

Through torture my joints are torn asunder.60. My limbs are destroyed, loathing covers me;

On my couch I welter like an ox

I am covered, like a sheep, with my excrement.

My sickness baffled the conjurers

And the seer left dark my omens.65. The diviner has not improved the condition of my sickness –

The duration of my illness the seer could not state;

The god helped me not, my hand he took not;

The goddess pitied me not, she came not to my side

The coffin yawned; they [the heirs] took my possessions.70. While I was not yet dead, the death wail was ready.

My whole land cried out: "How is he destroyed!"

My enemy heard; his face gladdened

They brought as good news the glad tidings, his heart rejoiced.

But I knew the time of all my family75. When among the protecting spirits their divinity is exalted.

...

...

Let thy hand grasp the javelin

Tabu-utul-Bel, who lives at Nippur,

80. Has sent me to consult thee

Has laid his ... upon me.

In life ... has cast, he has found. [He says]:

"[I lay down] and a dream I beheld;

This is the dream which I saw by night:85. [He who made woman] and created man

Marduk, has ordained (?) that he be encompassed with sickness (?)."

...90. And ... in whatever ...

He said: "How long will he be in such great affliction and distress?

What is it that he saw in his vision of the night?"

"In the dream Ur-Bau appeared

A mighty hero wearing his crown95. A conjurer, too, clad in strength,

Marduk indeed sent me;

Unto Shubshi-meshri-Nergal [the conjurer] he brought abundance;

In his pure hands he brought abundance.

By my guardian-spirit (?) he stopped (?),"100. By the seer he sent a message:

"A favorable omen I show to my people."

...

... he quickly finished; the ... was broken

... of my lord, his heart was satisfied.105. ... his spirit was appeased

... my lamentation ...

... good ...110. ...

... like ...

He approached (?) and the spell which he had pronounced (?),115. He sent a storm wind to the horizon;

To the breast of the earth it bore a blast

Into the depth of his ocean the disembodied spirit vanished (?);

Unnumbered spirits he sent back to the under-world.

The ... of the hag-demons he sent straight to the mountain.120. The sea-flood he spread with ice;

The roots of the disease he tore out like a plant.

The horrible slumber that settled on my rest

Like smoke filled the sky ...

With the woe he had brought, unrepulsed and bitter, he filled the earth like a storm.125. The unrelieved headache which had overwhelmed the heavens

He took away and sent down on me the evening dew.

My eyelids, which he had veiled with the veil of night

He blew upon with a rushing wind and made clear their sight.

My ears, which were stopped, were deaf as a deaf man's130. He removed their deafness and restored their hearing.

My nose, whose nostril had been stopped from my mother's womb –

He eased its deformity so that I could breathe.

My lips, which were closed he had taken their strength –

He removed their trembling and loosed their bond.135. My mouth which was closed so that I could not be understood –

He cleansed it like a dish, he healed its disease.

My eyes, which had been attacked so that they rolled together –

He loosed their bond and their balls were set right.

The tongue, which had stiffened so that it could not be raised

140. He relieved its thickness, so its words could be understood.

The gullet which was compressed, stopped as with a plug –

He healed its contraction, it worked like a flute.

My spittle which was stopped so that it was not secreted –

He removed its fetter, he opened its lock.

...

Conclusion

The Babylonian version of the piece concludes with the lines, "May he stroll along in happiness of heart daily ... He sang your praises ... your praise is sweet", which echo the first lines of the work:

I will praise the lord of wisdom, the considerate god,

Angry at night but relenting at daybreak

Marduk, the lord of wisdom, the considerate god,

Angry at night but relenting at daybreak. (Lenzi, 1)

As many of the lines of the Sumerian work appear in the later piece, notably in Tablet II, it is thought that the original most likely also concluded with praise for Marduk. Even in the Sumerian version's incomplete state, as noted, this conclusion is strongly suggested. The final message of the work, echoed by the Book of Job and Dialogue of a Man and His God, among other works, is that the divine can do whatever it wants and human attempts to understand the reasons will always fall short. The best one can do is give thanks for what one has and endure, through gratitude for the gifts that are given, the dark periods of one's life in the faith these, like one's brighter days, will also pass