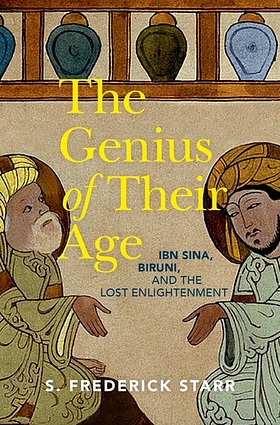

Ibn Sina and Biruni were two of the most outstanding thinkers to have lived between ancient Greece and the European Renaissance. These two giants of a lost era of enlightenment were born in Central Asia about the year 980. For six hundred years Ibn Sina's Canon of Medicine defined the field of medicine from Europe to India, while his thoughts on God and philosophy influenced Muslims, Jews, and Christians, including St. Thomas Aquinas.

As for Biruni, he measured the Earth's diameter more accurately than anyone before the 17th century, hypothesized the existence of North and South America as inhabited continents, and invented the first system of reckoning dates globally.

Forgotten Geniuses?

Despite their achievements, neither has become a household name for several reasons. Not the least of these are their names, which transcribed from the Arabic are bewilderingly complex: Abū-ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn-ʿAbdallāh Ibn-Sīna, and Abū al-Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Bīrūnī. Medieval Western translators Latinized Ibn Sina as Avicenna. Those Europeans in the Middle Ages who had even heard of Biruni conjured up several Latinized versions of his name, the most common of which was Alberonius.

In spite of their names, neither was an Arab. Both became known by their Arabic names because they wrote mainly in Arabic, the language of learning in the Muslim world, just as Latin was in the West. Ibn Sina and Biruni were both born within the borders of what is now Uzbekistan. and spent their lives in what is now Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan.

Notwithstanding their obscurity to the general public, the scholarly literature is bulging with encomia of these two men. Biruni has been hailed as "an 11th-century da Vinci," "one of the greatest scholars of all times," "forerunner of the Renaissance," a "phenomenon in the history of Eastern learning," "a universal genius," and simply, "The Master." In 1927, George Sarton, the Belgian-born chemist who pioneered the systematic study of the history of science, pronounced him "the finest monument to Islamic learning."

Ibn Sina has similarly been praised as "The Preeminent Master," "the Prince of Physicians," "by far the most influential of the Islamic philosophers," and "arguably the most influential philosopher of the pre-modern era." More than one European historian praised him as "the Father of Modern Medicine," while counterparts in the Eastern world have named him "The Leader Among Wise Men," and even "The Proof of God."

Achievements

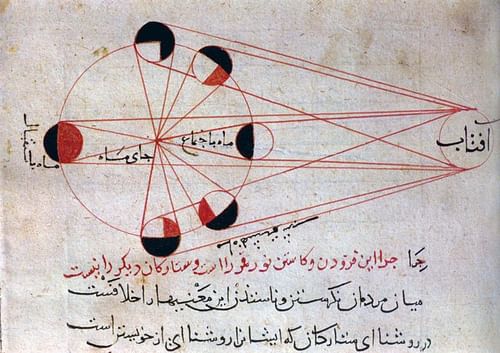

Scholars have long been plowing this field. Most, if not all, were champions of one or the other, Biruni or Ibn Sina, but few were of both. In the process of defending their hero, they advanced a heady list of claims regarding his preeminence. Biruni, for example, is said to have founded both astronomy and trigonometry as independent fields of enquiry and advanced the field of spherical trigonometry. Few surpassed him in asserting that mathematics can faithfully represent reality. Using a formula that did not reappear again until the 17th century, he devised the first example of a calculus of finite differences. Aided by simple but highly sophisticated instruments of his own design, as well as new methodologies in geometry and calculus, his scholarly champions claim that he measured the diameters of the earth and moon more accurately than anyone else until the 17th century. They further claim that he employed the same innovative method to expand the parameters of the known world and even hypothesized the existence of North and South America as inhabited continents.

These champions also credit Biruni with having invented the concept of specific gravity and weighing minerals to a degree of accuracy not surpassed until modern times. Further, he pioneered the fields of cultural anthropology and sociology and vastly expanded the study of the history of science, hydrostatics, and the comparative study of religion. One scholar has argued that he was the first to introduce Indian yoga philosophy to the Middle East and Western worlds. Several specialists maintain that he invented the concept of integrated world time and world history and that he preceded Europeans of the Renaissance in building a globe of the world and in propounding a theory of oceanography. His innovations in all these fields combined sophisticated mathematics with an appreciation of the impact of language, religion, and culture on human life.

As to Ibn Sina, his champions argue that he did nothing less than create a single, integrated, and comprehensive intellectual framework that encompassed philosophy, science, medicine, and religion. By means of his revisionist logic, he reconfigured Aristotle's grand synthesis of all knowledge, and in a manner that confirmed a place for religious faith, whether his own, which was Islam, or the other religions of the Book. He has also been credited for being a founder of scholastic philosophy. Further, experts on medieval thought argue that in his attempt to explain the nature of creation itself, St. Thomas Aquinas' Summa drew directly on Ibn Sina. Many also argue that Ibn Sina contributed to fields as diverse as geology, mathematics, and, perhaps above all, medicine.

Historians of science have advanced the claim that Ibn Sina summarized all known medical knowledge and ordered it under a single, logical, and accessible structure. Comprehensive in scope, his Canon of Medicine focused attention on neurological questions, the functioning of the brain, and the environmental and psychiatric conditions essential for the restoration and maintenance of health. Among his many innovations were the precise rules he laid down for the conduct of clinical trials of new medicines. Many argue that the Canon of Medicine served as the basis of medical education and practice throughout the Middle East, Europe, and parts of India for six centuries, and it is widely seen among experts as the single most enduring work in the history of medicine.

Modern Study of Polymaths

A problem in studying polymaths is that the expertise of most modern specialists rarely extends beyond one or two of the many relevant disciplines. Moreover, the present state of our knowledge of their lives prevents us from providing definitive portraits. To cite but one example, both Biruni and Ibn Sina, at certain phases of their lives, worked as senior statesmen, policymakers, and strategic thinkers. Yet all the official papers that documented their activities were destroyed many centuries ago or lost to neglect.

What we do know, however, is that the lives of these two thinkers were packed with drama, crises, and stunning achievements. Separated from their world by a millennium, we have much to gain from reflecting upon their lives and works today. The story of Ibn Sina and Biruni transcends the centuries, offering insights into their tireless efforts to expand the realm of human knowledge, and in a part of the world that today sometimes invites concerns over the role of advanced learning and science. That these two larger-than-life figures should inform such discussions a full millennium after their deaths is appropriate, for in the end, though the geniuses of their age, they rise above time and place, religion, and politics, to stand as citizens of the global world of ideas and giants of human achievement.