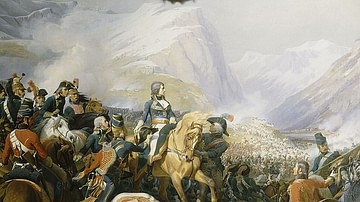

The Battle of Aspern-Essling (21-22 May 1809) was a major battle of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815). It saw an Austrian army under Archduke Charles defeat a French army led by Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815) as it attempted to cross the Danube River near Vienna. The battle marked Napoleon's first major defeat in ten years.

A New Austrian Army

In December 1805, Austria was defeated at the Battle of Austerlitz and forced to sue for peace with France. The peace was a costly one, forcing Austria to surrender its territories in Italy and southern Germany to France's allies and to recognize the Confederation of the Rhine, a league of German states under Napoleon's protection; the creation of the Confederation directly led to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, drastically reducing the Habsburgs' power in Central Europe. Over the next three years, Austria remained neutral as Napoleon's Grande Armée plowed across Europe, crushing the armies of Prussia and Russia in the War of the Fourth Coalition (1806-1807). However, Austria did not spend these years idly but was instead busy reforming its armies.

These reforms were spearheaded by Archduke Charles, brother of Austrian Emperor Francis I and commander-in-chief of the Austrian armies. Charles had been fighting the French since 1793 and was therefore familiar with what made the French armies so successful. He mimicked the corps d'armée system that had served Napoleon so well and created nine line and two reserve corps for the Austrian army. This would allow the Austrians a greater degree of mobility and would fix the clumsy administrative system that plagued the old army. Charles also implemented a French-style system of mass conscription by establishing the Landwehr, a militia that drew upon all males between the ages of 18-45 from the Austrian Empire's German-speaking provinces. The Landwehr could potentially field 180,000 men in addition to the 340,000 troops in the regular army.

As Charles' reforms came to fruition, a war party developed in the imperial court at Vienna that itched to get revenge on Napoleon. Centered around the empress consort Maria Ludovika, and involving several key ministers, the war party believed that Napoleon would never leave the Habsburgs to rule in peace and that it was necessary to attack the so-called "Corsican Ogre" to ensure the survival of the Habsburg empire. This faction saw its opportunity in July 1808, when a French imperial army surrendered to a Spanish force at the Battle of Bailén, part of Napoleon's ill-fated Peninsular War (1807-1814). Bailén marked the first major defeat of a French army since the start of the Napoleonic Wars, a good omen for Napoleon's enemies. The fact that 300,000 French soldiers, including the emperor himself, were busy fighting in Iberia seemed to be another indicator that now was the time to strike. Archduke Charles protested, claiming that he needed more time to implement his reforms. However, he was overruled by his brother, Emperor Francis, who agreed with the war party and ordered Charles to mobilize the army.

Surprise Attack

Austria's belligerent actions did not go unnoticed by the French. In January 1809, Napoleon left the Spanish front and returned to Paris, where he rushed through legislation that raised a new army of 230,000 men. While some of these were hardened veterans, most were raw conscripts called up from the conscription classes of 1809 and 1810. This new army, dubbed the Army of Germany, was stationed to the east of the Rhine to deter the Austrians from attacking. Its numbers were supplemented by soldiers from Napoleon's German allies, primarily Bavaria. Since Napoleon did not wish to provoke the Austrians, he decided to remain in Paris, and handed control of this army over to his trusted chief of staff, Marshal Louis-Alexandre Berthier. To take command of the army corps, Napoleon recalled some of his best marshals from Spain, including Jean Lannes, François-Joseph Lefebvre, and Jean-Baptiste Bessières.

Napoleon hoped that this would be enough of a deterrence to delay an Austrian attack until May. However, Archduke Charles launched his offensive a month earlier than Napoleon anticipated, and he invaded Bavaria on 10 April 1809 with 200,000 men. Berthier, who was a brilliant chief of staff but a less capable army commander, panicked; misinterpreting orders from Napoleon, he was unable to concentrate his army, meaning that the French corps were scattered between Augsburg and Munich, with Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout's III Corps isolated at Ratisbon, dangerously far ahead of the rest of the army. This position could have been disastrous for the French. But despite Charles' recent reforms, the Austrian advance proceeded at a snail's pace, throwing away their advantage of surprise. On 17 April, Napoleon arrived at the front and took over command from a relieved Berthier. His mere presence raised the spirits of his men, who were now eager to go on a counteroffensive.

Landshut Campaign

By 17 April, the Austrian army had crossed over the Isar River at Landshut. Archduke Charles' plan was to attack Ratisbon and destroy Davout's lone corps before mopping up the rest of the scattered French army; Charles hoped that a series of quick victories would convince French-occupied Germany to rise against Napoleon. The French emperor, meanwhile, decided he needed to concentrate his forces. He ordered Davout to abandon Ratisbon and link up with Marshal Lefebvre's Bavarian troops at Abensberg; Davout and Lefebvre would then pin down the Austrian advance while the rest of Napoleon's Franco-German army marched to Landshut, where it could threaten the Austrian rear and cut off its line of communications.

On 19 April, Davout's III Corps began marching toward Abensberg when it encountered elements of the Austrian III and IV Arméekorps near the villages of Teugen and Hausen. Davout held his ground and, after a bloody fight, continued on to Abensberg. He linked up with Lefebvre who had just beaten back another Austrian assault at Anholfen. With his army now united along a single front, Napoleon launched a sustained offensive on 20 April. In a series of engagements known collectively as the Battle of Abensberg, Napoleon managed to drive the Austrian left flank back across the Isar River, taking large numbers of prisoners in the process. The next day, Napoleon seized the town of Landshut. But before Napoleon could bask in his victory, he received word that Davout was being attacked by the main Austrian army near Eckmühl. Napoleon rushed to the aid of Davout, arriving in time to win a major victory over Archduke Charles' army at the Battle of Eckmühl (22 April).

The Austrians beat a disorderly retreat to Ratisbon, where Archduke Charles hoped to cross the Danube River and withdraw into Bohemia to regroup. Napoleon pursued, and on 23 April, he decided to assault the town directly rather than waste time carrying out a siege. After an artillery bombardment on the city's medieval walls, Marshal Jean Lannes was tasked with scaling the walls with ladders. The first three attempts failed, and Napoleon was wounded in the right ankle by a musket ball; immediately after his wound was dressed, the emperor rode up and down the battle line to show his men that he was alright. By mid-afternoon, Lannes' tired men refused to assault the Ratisbon walls for a fourth time. The frustrated marshal scoffed and exclaimed: "Oh well! I am going to prove to you that before I was a marshal, I was a grenadier – and so I am still!" (Chandler, 692) Lannes then grabbed a ladder and began running toward the walls, shouldering off his panicked aides-de-camp who tried to stop him. This roused the courage of his men, who charged toward the walls with a loud shout; they succeeded in scaling the walls, and by nightfall, Ratisbon was in French hands.

Although the French succeeded in taking the town, they had failed to secure the bridge, allowing Archduke Charles' army to slip away intact. Still, the Landshut campaign had been a great victory; in only a week of fighting, the French had won a string of battles and inflicted 30,000 Austrian casualties, an impressive feat for an army comprised mainly of conscripts. Moreover, Charles' retreat left the road to Vienna wide open, and on 13 May, the French army entered the Austrian capital after a brief bombardment. Although the Habsburg court had already been evacuated, the fall of Vienna was a major blow to Austrian morale.

Crossing the Danube

Despite Napoleon's swift victory, the war was not over. The French emperor's decision to take Vienna instead of chasing the Austrian army had allowed Archduke Charles time to lick his wounds and regather his forces. By mid-May, Charles marched out of Bohemia and stationed his army on the far side of the Danube River, to the north and east of Vienna. He encamped his army there, deciding to wait until he could be reinforced by his brother Archduke John who was commanding 30,000 Austrians in northern Italy. Napoleon, meanwhile, knew he had to destroy Charles' army before John had a chance to reinforce him, but Charles was on the opposite side of the Danube, and the Austrians had destroyed all the major bridges. Napoleon had to build his own bridge and, after consulting his engineers, decided that the best place to cross was at Lobau Island, to the south of Vienna; bridging materials could easily be floated downstream to this point, where the bridge could be constructed with artillery cover.

The French sappers got to work on the night of 19 May, and the work was completed a little behind schedule by noon of the next day. The corps of Marshal André Masséna was the first to cross over, scattering the scant Austrian defenses on the opposite bank and occupying the towns of Aspern and Essling. But before more French troops could get across, the Austrians floated a barge down the river that smashed through the bridge, forcing the French to spend precious time making repairs. The bridge was fixed by nightfall, and by the morning of 21 May, 25,000 French troops had reached the left bank of the Danube, gathered on the broad, flat plain known as the Marchfeld. However, most of the French army had yet to cross the river, and the crossing was stymied when the water level rose by almost a meter (3 ft). Napoleon grew increasingly anxious and even considered calling off the operation.

Archduke Charles had been aware that Napoleon was crossing at Lobau and had gathered his army at the northeastern edge of the Marchfeld plain. Charles had not contested the French crossing, desiring instead to attack Napoleon's army as it straddled the Danube, divided in two. At 10 a.m. on 21 May, Charles decided that the time was right and ordered an attack: three Austrian corps would attack Aspern, one would attack Essling, while the Austrian cavalry formed a link between the two wings; Charles had around 98,000 men in total. His attack would advance in columns to be performed across a 10-kilometer (6 mi) front. The white-coated Austrians got into position and commenced their attack around 1 p.m.

First Day: 21 May

The French had not been expecting an Austrian attack; indeed, Marshal Masséna had neglected to fortify Aspern and Essling. Therefore, the French were taken by surprise when the first elements of the Austrian I Corps appeared outside Aspern, their approach having been hidden by a low ridge and sudden dust storm. The Austrians, under Johann von Hiller, drove the French outposts into Aspern, where French General Gabriel-Jean Molitor managed to rally them and hold off the Austrian assault long enough to gather all four regiments of his division. Hiller's first assault was repulsed, but subsequent Austrian attacks continued all afternoon; by 5 p.m., three Austrian corps were outside Aspern in a half-circle. Once Charles ordered a general assault, General Molitor found that he was being squeezed from three directions. Fierce fighting continued into the twilight hours, as Aspern exchanged hands at least six times. Despite having to hold off three corps with only a single division, Molitor held his ground until he was reinforced by General Lagrand's division. By the time the fighting fizzled out, Aspern was a smoking ruin, but it remained in French hands.

While the Austrian attack on Aspern almost succeeded, their simultaneous assault on Essling went much poorer. The Austrian IV Corps under Prince Rosenberg assaulted Essling three times after 6 p.m. but was repulsed each time by the determined French defenders from Marshal Lannes' II Corps; by nightfall, not a single house in Essling had fallen to the Austrians. As the fighting raged in the two villages, Marshal Bessières led 7,000 French cavalrymen in several charges against the Austrian cavalry; one notable casualty in this action was the celebrated French cavalry general Jean-Louis d'Espagne, who was killed by an Austrian saber. By day's end, both army commanders were confident in their positions and prepared to renew the fight the following morning.

Second Day: 22 May

Napoleon took advantage of nightfall to filter more troops across the bridge, including the hardened division of General Jean-Vincent de Saint-Hilaire, which had played a vital role in many previous battles. By the dawn of 22 May, Napoleon had roughly 50,000 infantry, 12,000 cavalry, and 144 guns against nearly 100,000 Austrian soldiers and 260 guns. Fighting began at 5 a.m. when the Austrian I and VI Corps took advantage of the thick morning mists to launch an assault on the ruins of Aspern. Though this attack succeeded in capturing the town, the Austrians were forced out again by a French counterattack around 7 a.m. A simultaneous Austrian assault on Essling was also beaten back.

With both Austrian wings engaged, Napoleon saw a golden opportunity to attack the vulnerable Austrian center. He entrusted this task to the II Corps of Marshal Lannes, which began its charge at 7:30 amidst the sound of beating drums. The charge was met with waves of Austrian shot and shell, but the II Corps kept on coming, causing the Austrian line to waver. The Austrians may have been broken, had it not been for the personal intervention of Archduke Charles, who rushed into the fight at the head of the Zach Grenadier Regiment, bearing the regiment's flag in his own hands. The sight of their commander's valor inspired the Austrian troops, who held their ground and stopped Lannes' charge in its tracks. After bitter fighting, Lannes was forced to give ground. The French position worsened further when several Austrian projectiles punched fresh holes in the bridge, preventing Davout's corps from crossing and joining the battle.

As soon as Archduke Charles learned that the bridge was damaged, he ordered every Austrian corps to attack. By 10 a.m., savage fighting was raging around both villages; it was at this point that French General Saint-Hilaire was mortally wounded, only days after Napoleon had promised him a marshalate. At Essling, the Austrian IV Corps succeeded in driving the French out of their positions while the French center began to buckle under the pressure. Napoleon sent his Young Guard to retake Essling, but it failed to do so. The bridge, which had just been repaired, was smashed again by a flaming floating mill, leading Napoleon to realize that the battle had to be called off. As the emperor began organizing a withdrawal, his staff realized that he was within range of the enemy guns and begged him to retire across the river. Reluctantly, Napoleon agreed to do so, handing control of the army over to Lannes before withdrawing to Lobau Island shortly after 3 p.m.

Slowly, the French army retreated across the Danube; at 3:30 p.m., the moorings of the forward bridge were drawn back to Lobau Island. Scattered fighting continued in Aspern until 4 p.m., at which point boats arrived to evacuate the remaining French soldiers. Marshal Lannes remained on the opposite side of the river as he oversaw the retreat. At one point, Lannes was conferring with his friend, General Pierre-Charles Pouzet, when a cannonball tore off Pouzet's head mid-conversation. Covered in the blood and brains of his friend, and likely overwhelmed by shock, Lannes went and sat down at the edge of a ditch to compose himself, when a second cannonball struck him in the kneecap. Lannes was taken back to army headquarters where his left leg was promptly amputated. However, gangrene set in, and Lannes died nine days later. His loss was a major blow to Napoleon; Lannes had not only been one of France's finest marshals but had also been one of Napoleon's few close friends.

Aftermath

The Battle of Aspern-Essling resulted in heavy losses for both sides; the Austrians lost 23,340 killed and wounded while the French suffered between 20-23,000 losses. Yet the battle was undeniably a defeat for Napoleon; in fact, it was his first major defeat in a decade, since the Siege of Acre in 1799. The loss, which struck a major blow to Napoleon's reputation, was compounded by the loss of several irreplaceable officers including d'Espagne, Saint-Hilaire, and Lannes. Retreating across the Danube, Napoleon withdrew to Vienna to regroup; Archduke Charles failed to pursue, losing a golden chance to destroy Napoleon's army. Charles' failure to capitalize on his victory would prove to be fatal. A little over a month later, Napoleon would win a decisive victory at the Battle of Wagram (5-6 July), which would lead to Austria's defeat in the War of the Fifth Coalition.