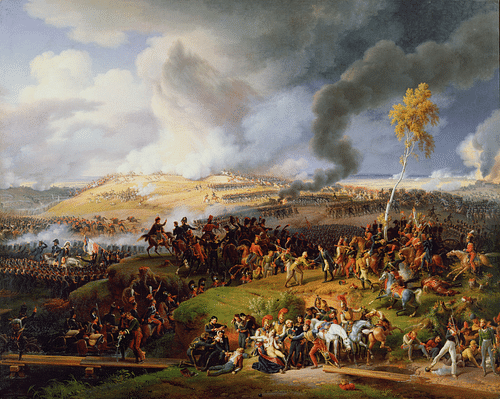

The Battle of Borodino (7 September 1812) was a major battle fought during Napoleon's invasion of Russia. It saw the French Grande Armée of Emperor Napoleon I (r. 1804-1814; 1815) narrowly defeat an imperial Russian army under Mikhail Kutuzov, before continuing on to briefly occupy Moscow. The battle was the bloodiest single day of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815).

Origins

On 24 June 1812, French Emperor Napoleon I crossed the Niemen River with his colossal Grande Armée, commencing his invasion of the Russian Empire. Though France and Russia had formed an alliance only five years before, the conflicting interests of the two empires caused relations to rapidly deteriorate; the breaking point came in December 1810, when Tsar Alexander I of Russia (r. 1801-1825) pulled his country out of the Continental System, Napoleon's large-scale embargo against the United Kingdom. Furious at this apparent betrayal, Napoleon spent the next year and a half assembling the largest invasion force Europe had yet seen: 615,000 men, 200,000 horses, 1,300 guns, and a supply train of 7,400 vehicles. Of the soldiers who comprised the Grande Armée, slightly less than half (302,000) were French; the rest (313,000) came from all corners of Napoleon's vast European empire and included Poles, Austrians, Prussians, Germans, Italians, Dutch, Spaniards, Portuguese, and others.

When Napoleon led this multinational army across the Niemen, his goal was not to conquer Russian land. Rather, he sought only to force Tsar Alexander to rejoin the Continental System and recognize French supremacy in Europe. To do this, Napoleon needed to destroy the Russian armies in a series of swift engagements; the French emperor anticipated that this would take less than three weeks. The Russians, meanwhile, had around 250,000 troops in the western provinces with which to oppose the French invasion. These men were dispersed across three separate armies and were therefore in danger of being attacked and defeated piecemeal before they could unite. The First Western Army of 129,000 men was stationed at Vilna (Vilnius) and was led by Mikhail Barclay de Tolly, a soldier of Baltic German and Scottish origin who was serving as commander-in-chief of Russia's armies. The Second Western Army of 58,000 men, led by the fiery Georgian Prince Peter Bagration, was about 160 kilometers (100 mi) to the south while Alexander Tormasov's Third Western Army was marching north from the Balkans.

Barclay de Tolly realized that if he held his ground against Napoleon's superior force, he would certainly be defeated; instead, he ordered all Russian armies to avoid engaging the enemy and to embark on a strategic retreat deep into Russian territory. As they retreated, the Russians were ordered to implement scorched earth tactics, whereby they destroyed everything of value to the invaders, including crops, windmills, bridges, depots, and livestock. Barclay's retreat, though sanctioned by the tsar, was unpopular amongst the Russian soldiers, who felt dishonored at having to give up so much territory without a fight. Though he complied with Barclay's orders, Prince Bagration himself complained about the retreat, grumbling that "Russians ought not to run away. We are becoming worse than the Prussians" (Lieven, 151). By the end of July, the Russian-born soldiers had come to loathe Barclay and the other Baltic German officers, who they believed did not truly care for the Russian cause.

Nevertheless, Barclay's plan was working. By the end of July, Napoleon had captured Vilna and Minsk but had been denied the major battle he desperately needed. As the Grande Armée advanced further into Russian territory, its ranks were thinned by starvation, desertion, and disease; only a month into the campaign, Napoleon had already lost around 100,000 men. Despite this success, Russian public opinion would not allow Barclay to keep running forever. On 4 August, Barclay's and Bagration's armies united at Smolensk, where the Russian officers pressured Barclay into making a stand, threatening to mutiny. The Battle of Smolensk (16-18 August) was the first large-scale battle of the war; the Russians held off wave after wave of French assaults in the suburbs of the city, which was soon engulfed in flames. Barclay knew his troops could not hold out much longer, and he decided to retreat to preserve his army. Thus, Napoleon was left in command of Smolensk, which was littered with corpses; 10,000 French and 12,000 Russians had been killed or wounded.

Kutuzov Takes Command

Barclay's decision to abandon Smolensk may have saved the Russian army, but it cost Barclay his job. In St. Petersburg, Tsar Alexander was pressured by the Russian nobility to replace the German Barclay with a Russian national; the best option was Mikhail Kutuzov, a 65-year-old veteran from a well-respected aristocratic family, whose decades of military service to the Russian Empire were evidenced by the battle scars on his face. Though Alexander himself was no great admirer of Kutuzov, the old soldier was popular amongst both the Russian nobility and the common soldiers. Kutuzov arrived to take command on 29 August, and the excitement of the army was recorded by one Russian lieutenant:

The moment of joy was indescribable: this commander's name produced a universal rebirth of morale among the soldiers…the veterans recalled his campaigns in Catherine [the Great]'s time, his many past exploits…they remembered his miraculous wound from a musket ball which passed through both sides of his temple. It was said that Napoleon himself called Kutuzov the old fox and that Suvorov had said that 'Kutuzov…can never be tricked'. Such tales…strengthened the soldiers' hope for their new commander, a man with a Russian name, mind, and heart, from a well-known aristocratic family, and famous for his many exploits (Lieven, 188).

Kutuzov took command with the expectation that he would stand and fight. Having taken Smolensk, the French army was headed for Moscow, a city that the Russians could not bear to give up; alongside being the largest city in the Russian Empire, Moscow held much cultural, historical, and religious significance. Kutuzov himself had remarked that "the loss of Moscow entails the loss of Russia itself" and had promised the tsar that he would die before allowing the city to fall (Lieven, 210). As the Russian army continued to pull back toward the city, staff officers were sent up the road to scout out potential locations for a stand. It was determined that the best defensive location was the area around Borodino, a village about 124 kilometers (77 mi) west of Moscow. On 3 September, Kutuzov moved his army into position and waited for the approach of the French.

Clash at Shevardino

The battleground of Borodino was mostly open countryside, though it was interspersed with various streams, ravines, woodlands, and hamlets. The Kolocha River, a tributary of the Moskva, ran parallel to the Smolensk-Moscow highway, while the Moskva itself flowed to the northeast. As noted by historian David G. Chandler, the "broken and intersected" terrain was favorable to the Russian defenders since "any force attacking from westward would find it virtually impossible to maneuver without breaking formation" (795). The Russians added to the natural defenses by constructing earthworks. A 'Great Redoubt' was constructed in the center of the Russian line and was defended by 20 guns. Additionally, three arrow-shaped fortifications, called flèches, were built atop hills toward the left of the Russian line. These were named the 'Bagration flèches' after the Russian general.

The Russians also built a pentagonal-shaped redoubt at the hamlet of Shevardino, on the far left of the Russian line. However, Kutuzov decided that this position was too vulnerable and ordered his left flank to pull back to a more secure position. On 5 September, as the Russians were executing this maneuver, the redoubt at Shevardino was attacked by the leading elements of Napoleon's army. Prince Andrei Gorchakov and the 27th Russian Division stubbornly defended the redoubt for hours but were ultimately forced to withdraw once the French began enveloping the fortification. This action cost the French 4,000 casualties and the Russians 6,000. It also caused disorder amongst the Russian left flank, which was forced to form an improvised position around the town of Utitsa.

Preparations

The next day, 6 September, passed in foreboding silence as both armies prepared for battle. To raise the spirits of his men, Kutuzov had the famous icon of the Smolensk Mother of God carried down the Russian line. The icon, which had been saved from the fires of Smolensk, reminded the Russian troops of the fate that would befall Moscow and their Orthodox religion if the French prevailed.

The extreme right of the Russian line was anchored at the confluence of the Kolocha and Moskva rivers. The Russian position extended along the length of the Kolocha and ended around Utitsa on the far left; the Russian center and left were filled with dense woods. Barclay's First Army was deployed on the Russian right while Bagration's Second Army was on the left; the village of Borodino itself served as the junction where the two armies met. Nikolai Raevsky's VII Corps defended the Great Redoubt in the center of the battlefield, while Mikhail Borozdin's VIII Corps occupied the Bagration flèches. Kutuzov himself commanded form his headquarters at Gorki, behind the Russian lines. The Russians had around 120,000 men and 640 guns.

There was no such religious ceremony in the French camp that day. Instead, officers read out a proclamation written by the emperor that spoke of patriotism and glory. A portrait of Napoleon's infant son, the King of Rome, was set outside his tent so the whole army could look upon their future emperor. The fact that he was so far from France made Napoleon hesitant to plan any risky maneuvers, causing him to shoot down a suggestion from Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout that 40,000 men be sent on a night attack against the Russians' vulnerable left flank. Instead, Napoleon ordered a frontal assault along the entire Russian line, a plan that Chandler likens to "a series of sledgehammer blows" (799). The uninspired nature of this plan was uncharacteristic of Napoleon, and historians have since speculated that his judgment was inhibited by the high fever and bladder inflammation he was suffering from at the time. The Grande Armée had roughly 103,000 infantry, 28,000 cavalry, and 587 guns.

The Battle Begins

At 6 a.m. on 7 September 1812, the tranquil silence of dawn was shattered by the roar of 100 French cannons, directed against the Russian center. Half an hour later, Napoleon's stepson, Prince Eugène de Beauharnais, led the French IV Corps in an assault on the village of Borodino. Concealed by thick early morning mists, Eugène's attack caught the Russian Guards Jaeger Regiment by surprise; the Russians were driven out of Borodino with heavy losses. Prince Eugène pressed on to the heights of Gorki, where he was set upon by the Russian reserves. After sustaining severe losses, Eugène was forced back into Borodino, where he established defensive positions at 7:30 a.m.

Meanwhile, Marshal Davout launched an attack on the Bagration flèches, on the center-left of the battlefield. Davout committed three of his best divisions (22,000 men) which came under concentrated fire from the Russian cannons as they emerged from the woods. Despite taking heavy losses, Davout's divisions continued their advance, eventually making it to the earthen walls of the flèches. In the savage hand-to-hand fighting that followed, Borozdin's Russian troops refused to give ground; one Russian grenadier regiment was annihilated during the fighting, and Borozdin himself was killed, but the Russian stubbornness paid off. Multiple French assaults were repelled, and several French generals were killed; Davout himself was wounded, as was his replacement, General Jean Rapp. By 7:30, Davout's troops had won control of all three flèches, but they were soon driven out again by Prince Bagration, who led a spirited counterattack. French Marshal Michel Ney renewed the French assault, forcing Bagration to appeal to Barclay for aid.

Since the flèches were so pivotal, Bagration was able to draw in reinforcements from both the left and right, which weakened the Russian left wing at Utitsa, commanded by Nikolai Tuchkov. Consequently, Tuchkov found himself hard pressed when he came under attack by Prince Józef Poniatowski's 10,000 Polish troops. Poniatowski successfully outflanked the Russians and forced Tuchkov out of Utitsa village; however, Poniatowski was subsequently pushed out of the village by a fierce Russian counterattack, during which Tuchkov was killed. Fighting around Utitsa lasted throughout the day, as Poniatowski's Poles were reinforced by General Jean-Andoche Junot's Westphalian troops.

Attack on the Great Redoubt

For two hours after his capture of Borodino, Prince Eugène unleashed a barrage of artillery fire on the Russian defenders of the Great Redoubt. At 8:30, Eugène launched an assault, storming the redoubt and driving off Raevsky's Russian troops; however, Eugène's control of the Great Redoubt was short-lived as he was soon forced out again by a Russian counterattack. It was at this point that Alexander Kutaisov, commander of the Russian artillery, was killed, rendering the Russian cannons nearly useless for the rest of the battle. Meanwhile, the French committed more troops against the flèches; at around 10 a.m., Prince Bagration was mortally wounded, his leg smashed by shrapnel. News of his loss disheartened the Russian troops, who abandoned the flèches.

Seeing their opportunity, the French cavalry charged forward, however, Russian discipline held out and the troops reformed behind a ravine near the Psarevo plateau. The French cavalry under Joachim Murat, King of Naples, launched several attacks to dislodge them, but the Russian troops withstood each charge. Murat soon realized that the Russians could only be broken by Napoleon's Imperial Guard, which was the only French unit yet to be committed to the battle. Murat begged Napoleon to send in the Guard, a call that was soon echoed by Eugène, Davout, and Ney; yet each time, Napoleon refused to do so. Napoleon's refusal to send in the Guard has long been criticized. Had he done so, some historians speculate that he could have eliminated the Russian army and perhaps even won the war, but Napoleon did not want to risk losing the Guard so far from home, understanding that he would need it intact in the event of a retreat.

Napoleon's failure to commit the Guard allowed Kutuzov space to tighten up his line. Around midday, the Russians achieved a small success when 8,000 cavalrymen under General Fedor Uvarov attacked Prince Eugène's rear, winning more time for the Russians to organize their defenses on the Great Redoubt. At 2 p.m., 400 French guns opened fire on the redoubt, followed by a charge from three divisions of Eugène's troops. As Eugène's infantry engaged in a frontal assault, General Auguste de Caulaincourt led his cavalry around to strike through the Russian rear. Though Caulaincourt was killed, this maneuver caused panic in the Russian lines and allowed Eugène's infantry to sweep over the redoubt's walls. The four Russian regiments garrisoning the Great Redoubt were killed almost to a man before Eugène finally captured the fortification.

However, Barclay had managed to set up a defensive line to the east of the Redoubt, preventing Eugène from capitalizing on this success. It was at this point that Napoleon was once again urged to send his Guard to sweep the Russians from the field, but the emperor once again refused. Although Napoleon controlled the battlefield, he was unable to destroy the Russian army, which withdrew half a mile before setting up a new defensive line. The French shelled the new Russian position, but they were too exhausted to pursue; after twelve hours of bitter fighting, the Battle of Borodino was over.

Aftermath

Borodino marked the bloodiest day of the Napoleonic Wars; indeed, it was the single bloodiest day of battle in military history, not to be surpassed until the First Battle of the Marne over a century later. The Grande Armée had lost at least 32,000 killed or wounded, losses that they would not be able to make up so deep in the heart of Russia. The Russians suffered even worse casualties, losing 45,000 killed or wounded; 22 Russian generals became casualties, most notably Prince Bagration, who would die of his wounds on 24 September. In total, there were over 70,000 casualties in only twelve hours.

Aware that another day of fighting might cost him his entire army, Kutuzov retreated under the cover of darkness. He pulled back to the town of Fili on the outskirts of Moscow where, on 13 September, he held a war council to answer one question: defend Moscow or save the army? This question led to a heated argument amongst the Russian generals, who were loathe to see the heart of the empire fall into French hands. However, Kutuzov correctly assessed that if the army stood and fought, it would likely be destroyed, and Moscow would be lost anyway. With a heavy heart, he decided to give up Moscow to allow the army to fight another day. The city was evacuated, and Napoleon entered it on 15 September.

Napoleon's occupation of Moscow would not last long, and he would order a retreat on 18 October, after failing to reach a peace agreement with the tsar. As his army retreated from Russia it fell victim to the brutal Russian winter and was harrassed by Kutuzov's pursuing army. By the time it recrossed the Niemen in early December, the Grande Armée had lost half a million men, a catastrophe from which it would never fully recover.