Corn (maize) was central to the lives of Native Americans across North, Central, and South America. Maize was introduced to North America from Mesoamerica c. 700/900 CE and transformed the lives of the indigenous peoples. Every tribal nation has an origin story of this gift that came from the gods to feed the people, including the Sioux.

In some stories, corn is a gift of the Corn Mother, in others it came from the Old Woman Who Never Dies, a corn spirit who also taught the people to give proper thanks, and in others, Corn itself was a deity who gave itself for the good of the people. A Sauk tale relates how two hunters, sitting by a fire, offered roast venison to a beautiful woman who visited them and seemed hungry. In gratitude for their generosity, she told them to return to the spot in a year and, when they did so, they found corn, beans, and tobacco growing where she had sat.

In an Abenaki tale, a man living alone and yearning for company is visited by a beautiful woman who tells him to set fire to a field and, when it is burnt over, to drag her by the hair across it. He refuses at first, but she tells him he must do as he is told for the greater good and, if he does, she will remain with him as a constant companion. After he has dragged her across the field, she tells him to look for stalks that will appear as grass but will have something that looks like hair coming from them when they are ripe – then she vanishes. When the corn appears, the man recognizes the silk of the cornstalk as the woman's hair and is comforted in knowing she is always with him.

The stories of other nations follow along similar lines in recognizing and honoring corn as a gift from the gods or some benevolent, supernatural agency. The Sioux story of The Gift of Corn follows this same paradigm, except instead of a beautiful young woman or older matron, it is the spirit of corn itself that calls an old hermit from his tent and invites him to its home.

Text

The following version of the story comes from Myths and Legends of the Sioux (published 1916) by Marie L. McLaughlin, a one-quarter Sioux who lived on their reservations for 40 years. The story is also featured in Voices of the Winds: Native American Legends by Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark.

Alone in a deep forest, far from the village of his people, lived a hermit. His tent was made of buffalo skins, and his robe was made of deerskin. Far from the haunts of any human being, this old hermit was content to spend his many years.

All day long, he wandered through the forest, studying the different plants and collecting roots. The roots he used as food and as medicine. At long intervals some warrior would arrive at his tent and get medicinal roots from him for the tribe. The old hermit's medicine was considered far superior to all others.

One day, after a long ramble in the woods, the hermit came home so tired that, immediately after eating, he lay down on his bed. Just as he was dozing off to sleep, he felt something rub against his feet. Awakening with a start, he noticed a dark object. It extended an arm toward him. In its hand was a flint-pointed arrow.

"This must be a spirit," thought the hermit, "for there is no human being here but me."

A voice then said, "Hermit, I have come to invite you to my home."

"I will come," the old hermit replied. So he arose, wrapped his robe around him, and started toward the voice.

Outside his door, he looked around, but he could see no sign of the dark object.

"Whatever you are, or wherever you be," said the hermit, "wait for me. I do not know where to go to find your house."

He received no answer, nor did he hear any sound of someone walking through the brush. Reentering his tent, he lay down and was soon fast asleep.

The next night he again heard the voice say, "Hermit, I have come to invite you to my home."

The hermit walked out of his tent to find the person with that voice but, again, he found no one. This time he was angry, because he thought that someone was making sport of him. He was determined to find out who was disturbing his night's rest.

The next evening, he cut a hole in the tent large enough to stick an arrow through. Then he stood by the door, watching. Soon, the dark object came, stopped outside the door, and said, "Grandfather, I came to –" But he never finished his sentence. The old hermit had shot his arrow. He heard it strike something that produced a sound as though he had shot into a sack of pebbles.

Early the next morning, the hermit went out and looked at the spot near where he thought his arrow had struck some object. There on the ground lay a little heap of corn, and from this little heap a small line of corn lay scattered along a path. The old hermit followed this path into the woods.

When he reached a small mound, the trail ended. At its end was a large circle from which the grass had been scraped off clean.

"The corn trail stops at the edge of this circle," the old man said to himself. "So this must be the home of whatever invited me."

He took his big bone axe and knife and proceeded to dig down into the center of the circle. When he got as far down as he could reach, he came to a sack of dried meat. Next, he found a sack of turnips, then a sack of dried cherries, and then a sack of corn.

Last of all was another sack, empty except for one cup of corn. In the other corner was a hole where the hermit's arrow had pierced the sack. From this hole the corn had been scattered along the trail, which had guided the old man to the hiding place.

From this experience the hermit taught his people how to keep their provisions while they were traveling.

"Dig a pit," he explained to them, "put your provisions into it, and cover them with earth."

By this method, the Sioux used to keep provisions all summer. When fall came, they would return to their hiding place. When they opened it, they would find all their provisions as fresh as they were the day they had been placed there.

The people thanked the old hermit for his discovery of this method of preserving their food. And they thanked him for his discovery of corn, the first they had seen. It became one of the most important foods the Indians knew.

Importance of Corn & Prayer of Praise

Corn, beans, and squash made up the 'three sisters' of agriculture developed by the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Of these three, corn was especially important in that it fed both humans and their domesticated animals and could be used in making a variety of foodstuffs. Scholar Adele Nozedar comments:

A vitally important crop for the Native Americans, maize proved to be nutritious and versatile. Foodstuffs taken from the grain include popcorn, hominy, flour, and meal, among others. Maize grain is used as food for both humans and animals. Maize is often referred to as "Indian corn" … Because maize is such an important crop, it stands to reason that there is a great deal of mythology surrounding its provenance. A gift from the gods themselves, "Mother Corn" was considered equal to the gift of life itself. The corn harvest was celebrated extensively during all phases of its growth, from planting through to its ripening and eventual harvest. (275-276)

In the above story, Corn itself calls the old hermit from his tent and it is suggested that he was chosen because his "medicine was considered far superior to all others." This line is not only referencing the medicinal roots that warriors came to him for but also his "medicine" – his personal spiritual power – which would have allowed him access to the spirit world and the realms of the unseen. Although under normal circumstances it would have been inhospitable to shoot an arrow at a guest outside one's door, in this case, the act serves as a kind of acceptance of the invitation offered, especially since the corn spirit first approaches him with a "flint-pointed arrow." The old hermit, at first, follows the conventional etiquette of rising to greet a visitor, but when this proves futile, he resorts to firing his arrow at the voice, which, presumably, he would have understood as the right action because of his spiritual insight.

In following the corn trail, he is led to a circle and digs down into the center. This part of the story evokes the image of the Medicine Wheel – "a central stone surrounded by an aureole of stones, radiating from that central stone to the outer circle, like spokes" (Nozedar, 285). The circle represented eternity, the changing of the seasons in a cyclic pattern, and so the underlying nature of existence. Symbolically, the old hermit retrieves the corn from the eternal nature of life itself.

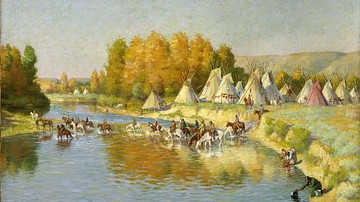

The cultivation of corn transformed many tribal nations from hunter-gatherers to sedentary agriculturalists, but the Sioux retained the hunting-gathering lifestyle because it was necessary in following their main resource for food, clothing, homes, and tools: the buffalo. The cultural combination of hunter-gatherers/pastoral agriculturalists is noted in this tale as the origin of corn is given along with how best to preserve one's provisions when one broke a given camp to travel to another or hunt the buffalo.

As noted, different tribal nations have different origin tales concerning corn, but this is also true within a given nation. The above is only one of the many Sioux origin tales of corn and another comes in the form of a prayer of praise usually translated with the title An Address to Mother Corn. The following comes from Voices of the Winds by Edmonds and Clark:

In ancient times, the Great Spirit Above sent Mother Corn to our people to be their friend and helper, to give them support and health and strength. She has walked with our people on the long and difficult path that they have traveled from the faraway past, and now she marches with us toward the future.

In the dim, distant past days, Mother Corn gave food to our ancestors. As she gave it to them, she now gives it to us. And as she was faithful and bountiful to our forefathers and to us, so will she be faithful and bountiful to our children. Now and in all time to come, she will give to us the blessings for which we have prayed.

Mother Corn leads us as she led our fathers and our mothers down through the ages. The path of Mother Corn lies ahead, and we walk with her, day by day. We go forward with hope and confidence in the future, just as our ancestors did during all the past ages. When the lonely prairie stretched out wide and fearful before us, we were doubtful and afraid. But Mother Corn strengthened and encouraged us.

Now Mother Corn's return makes our hearts glad. Give Thanks! Give thanks to Mother Corn! She brings us a blessing. She brings us peace and plenty. She comes from the Great Spirit Above, who has brought us good things.

Conclusion

The prayer combines the origin story with praise and the promise of the future in which Mother Corn will continue to guide, encourage, and give gifts to the people as she has in the past. This is similar in spirit to the Sioux story of White Buffalo Calf Woman who was sent to the people by Wakan Tanka (Great Mystery or Great Spirit) to bring them the seven sacred rites and the Sioux ceremonial pipe. In that story, as long as the pipe was used properly, the people would be happy and prosper but White Buffalo Calf Woman would still be watching over them from afar and would one day return to reset the balance and harmony of the world. At the same time, however, the spirit of White Buffalo Calf Woman would inspire and encourage the people, even if they could not see her or feel her presence.

In the version of the White Buffalo Calf Woman story as given by the Oglala Lakota Sioux holy man Black Elk (l. 1863-1950), when the mysterious woman arrives among the people, she sings this song:

With visible breath I am walking.

A voice I am sending as I walk.

In a sacred manner I am walking.

With visible tracks I am walking.

In a sacred manner I am walking. (295)

White Buffalo Calf Woman includes "with visible breath" and "with visible tracks" to assure the people that she is real, not a ghost, and states twice that she is walking "in a sacred manner" to establish that she comes from the Great Spirit Above and so her words should be taken as truth as she is a living being of a divine nature.

In this same way, Mother Corn is sent by the Great Spirit to provide for the people, and she joins the spirits of the ancestors, entities like White Buffalo Calf Woman, and the Great Spirit in caring for and guiding the people on their path. An Address to Mother Corn is still recited by the Sioux today in thanksgiving, and the story of The Gift of Corn is still told to maintain the traditional culture of the people and assure them that Mother Corn is with them always, walking beside them, helping them to maintain balance and hope for the future.